Mark J. Terrill/AP

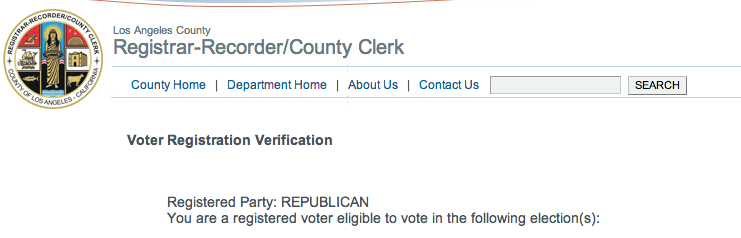

The NBA weighed in Tuesday on the calamity that is racist Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling, handing down a lifetime ban from the NBA (which is a big deal) and a $2.5 million fine (which isn’t, really). Professional sports team owners have been known to be assholes in all sorts of ways, but some take it to another level. Here are four owners who, like Sterling, caused controversy thanks to their racism, but unlike Sterling never got the boot because of it.

Marge Schott, Cincinnati Reds:

Marge Schott only owned the Cincinnati Reds for 15 years, but in that time the equal-opportunity racist uttered slurs against blacks, Asians, gays and Jews. She was fined $25,000 in 1993 ($41,000 in today’s dollars) and suspended from day-to-day operation of the Reds for a year. She got in trouble in 1996 for reiterating earlier comments about how Hitler started off as a good leader but later took things too far. Some choice nuggets: “Only fruits wear earrings,”; referring to one of her black players as her “million-dollar nigger,”; and referring to one of her former marketing directors as a “beady-eyed Jew.” Schott eventually caved to MLB penalties and public pressure, selling most of her shares in 1999.

Tom Yawkey, Boston Red Sox:

Tom Yawkey owned the Boston Red Sox from 1933-1976. Many know that he was a recalcitrant racist, fighting integration until 1959 and giving the Red Sox the dubious distinction of being the last integrated team in baseball, a full 12 years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. Even as he tried to defend himself from charges of racism, he told Sports Illustrated in 1965 that “colored people” were “clannish” and blamed them for the perception that he was racist.

George Marshall, Washington football team

George Preston Marshall bought the Boston Braves in 1932. Four years later, he had changed the team’s name to the [Redacted] and moved it to Washington, DC. While he left a legacy of change within the NFL—championing splitting the league into two divisions, deciding a champion with a playoff system, and accepting the forward pass—Marshall is best remembered for decades of unrepentant racism. He steadfastly refused to integrate his team, even after every other owner in the NFL had done so, leading Baltimore African-American sportswriter Sam Lacy to dub Washington the “lone wolf in lily-whiteism.” The team signed its first black players only after the federal government threatened to revoke its stadium lease in 1961.

Despite all his work opposing integration, Marshall was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the website of which lists his contributions to the NFL with only a passing note of how he “endured his share of criticism” for his racism. At Marshall’s funeral in 1969, then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle said, “Mr. Marshall was an outspoken foe of the status quo when most were content with it.” Where it counted, though, Marshall was exactly the opposite.

Calvin Griffith, Minnesota Twins

Calvin Griffith inherited the Washington Senators baseball team from his uncle Clark Griffith in 1955. Despite claiming the team would stay in Washington “forever,” Griffith moved the franchise to Minnesota in 1961, where it became the Minnesota Twins. While that may have made him a DC sports pariah, Griffith’s low point came in 1978 during a speech in Waseca, Minnesota. Local reporter Nick Coleman was there to write down what happened when the owner was asked why he had moved the team:

At that point Griffith interrupted himself, lowered his voice and asked if there were any blacks around. After he looked around the room and assured himself that his audience was white, Griffith resumed his answer. “I’ll tell you why we came to Minnesota,” he said. “It was when I found out you only had 15,000 blacks here. Black people don’t go to ball games, but they’ll fill up a rassling ring and put up such a chant it’ll scare you to death. It’s unbelievable. We came here because you’ve got good, hardworking, white people here.”

Multiple black players requested trades from the Twins after the comments were made public, with future hall-of-famer Rod Carew telling Jet Magazine, “I’m not going to be another nigger on his plantation.” Griffith sold the Twins in 1984. Twenty-six years later, the team built a statue of him.