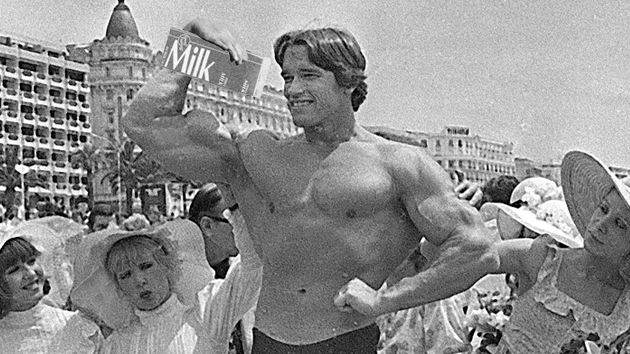

Milk is for babies, eh?Arnold: AP; Milk: Hemera Technologies/Thinkstock

Remember the backlash against the use of recombinant bovine growth hormone (rbGH)? Many commercial dairies now market their milk as free of this synthetic hormone, but that label may not tell you everything you need to know. Thanks to the way it is produced nowadays, milk from a commercial dairy is likely to contain much higher levels of natural sex hormones than you’d find in milk from a traditional (pre-industrial) dairy herd. And that could pose an rbGH-type problem. Some research suggests that elevated levels of these hormones may affect childhood development and raise a person’s cancer risk.

“The milk we drink today is quite unlike the milk our ancestors were drinking,” Harvard researcher Ganmaa Davaasambuu, an expert on milk-related illnesses, said during a 2006 talk at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. It “may not be nature’s perfect food.”

In the early 2000s, Davaasambuu began investigating why the rate of prostate cancer in Japan, while much lower than that of the United States, had increased 25-fold over the past 50 years. She and a colleague, the Japanese doctor Akio Sato, examined 36 years of dietary data in Japan and found that the incidence of, and mortality from, prostate cancer correlated most closely with the consumption of milk. Dairy products weren’t widely available in Japan until after WWII, when it imported American cows and dairy techniques, and a new law, enacted in 1954, mandated that schoolchildren drink 200 milliliters of milk at every school lunch.

In a follow-up study, Davaasambu found that milk consumption strongly correlated with the rates of breast, ovarian, and uterine cancers in 40 countries. Part of the problem, she believed, was that milk contains high levels of sex hormones such as estrogen. It’s well known that estrogens can induce prostate cancer in rats, and some epidemiological studies (but not others) have associated higher blood levels of estrogens in humans with prostate cancer risk. Estrogen imbalances have also been linked to breast cancer, and milk may be a delivery vehicle for the hormone. A 2004 study published in the International Journal of Cancer found that rats fed a diet of milk developed more and larger mammary tumors than those fed a diet of artificial (non-dairy) milk.

If milk does increase our risk of developing certain cancers, Davaasambuu wondered, then why aren’t those cancers more common in traditional cow herding societies? Searching for answers, Sato, her Japanes colleague, took his team to Mongolia, where breast and prostate cancer rates are low. They discovered that whole milk from Japanese Holsteins contains far more estrogen and progesterone (67 percent and 650 percent, respectively) than whole milk from Mongolian cows. If Davaasambuu’s theory is correct, the difference in hormone levels could help explain the difference in cancer rates between the two populations.

The reason that milk produced in America and Japan has more sex hormones than Mongolian milk is simple. The free-range cows kept by Mongolian nomads get pregnant naturally and are milked for five or six months after they give birth. In Japan and the United States, the typical dairy cow is milked for 10 months a year, which is only possible because she is impregnated by artificial insemination while still secreting milk from her previous pregnancy. Milk from pregnant cows contains far higher hormone levels than milk from nonpregnant ones—five times the estrogen during the first two months of pregnancy, according to one study, and a whopping 33 times as much estrogen as the cow gets closer to term.

As it turns out, the difference in hormone levels between Mongolian and American milk may indeed be significant enough to affect cancer rates. For example, a 2007 study published in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology found that rats fed commercial milk developed mammary tumors more often than those fed traditional milk. Other studies suggest a possible link between milk hormones and ovarian and uterine cancers: Davasaambuu found that rats fed on commercial milk had uteruses that were significantly heavier than those of rats on a dairy-free diet. A similar study published in 2010 in the journal Environmental Health and Preventative Medicine showed that a diet of traditional milk also affected rat uteruses, but not as much as a diet of commercial milk, which resulted in uteruses about 25 percent heavier on average.

At a 2006 symposium on milk, hormones, and human health in Boston, Davasaambuu and Sato went so far as to suggest that dairy companies add a new category of premium milk to their offerings: Milk produced exclusively from non-pregnant cows.

Of course, as Davasaambuu acknowledges, the science is far from settled. A 2012 study published in the Journal of Dairy Science found that feeding commercial milk to rats had no effect on uterine weights, for example. More animal and human tests must be conducted before scientists can draw firm conclusions, she says.

Health researchers are also interested in how hormones in commercial milk might affect development. In research published in 2007, Davasaambuu found that the blood-hormone levels of Mongolian third graders jumped after a month of being fed commercial American milk. A 2010 Japanese study saw similar results in children and adults—men’s testosterone levels decreased after they began drinking commercial milk. “Sexual maturation of prepubertal children could be affected by the ordinary intake of cow milk,” the researchers concluded.

Despite avid public interest in Davasaambuu’s milk research—”People are emailing me on almost a daily basis,” she told me—her lab and others have conducted few new studies in recent years. “Milk is a very complex food; there are a lot of good things and also not very good things,” which can make it hard to study, she noted. For instance, research suggests that other milk components, including calcium (in excess) and a hormone called insulin-like growth factor can also cause health problems.

Davasaambuu wanted to further compare the health effects of Mongolian and American milk, but in 2008 the National Institutes of Health denied her Harvard lab’s funding application, arguing that the dairy systems and human populations in the two countries were too different to merit comparison. Since then, she has cobbled together private funding for another study of 350 Mongolian schoolchildren, but hasn’t yet published the results. Mongolian authorities resisted the study, fearing their kids were being used as guinea pigs.

There are certainly downsides to living in a traditional society such as Mongolia, whose infant mortality rate, for example, is almost four times that of the United States. And the average Mongolian cow produces just 1.3 gallons of milk per day, compared with 9 gallons from the average American Holstein. Mongolian children drink one-third less dairy than their American counterparts. But judging from Mongolia’s low cancer rates, at least, its habit of drinking judicious amounts of traditionally produced free-range milk might be just what the doctor ordered.