<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hobby_Lobby,_Trexlertown.JPG">CyberXRef</a>/Wikimedia Commons

On Tuesday, the US Supreme Court will hear arguments in Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby Inc., the most closely watched case of the year. The stakes are high. Thanks to novel legal arguments and bad science, a ruling in favor of the company threatens any number of significant and revolutionary outcomes, from upending a century’s worth of settled corporate law to opening the floodgates to religious challenges to every possible federal statute to gutting the contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act.

Hobby Lobby is a privately held, for-profit corporation with 13,000 employees. It’s owned by a trust managed by the Green family, devout Christians who run the company based on biblical principles. They close their stores on Sundays, start staff meetings with Bible readings, pay above minimum wage, and use a Christian-based mediation practice to resolve employee disputes. The Greens are even attempting to build a Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC.

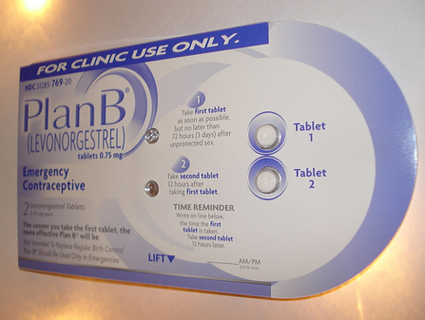

The Greens contend that the ACA’s requirement that health insurance plans cover contraception will force them to choose between violating their religious beliefs or suffer huge financial penalties for violating the law. They don’t object to covering all contraception, only the emergency contraceptive pills Plan B and Ella and intrauterine devices (IUDs), which they (erroneously) believe are abortifacients. But the Greens aren’t the ones who’d be providing the health insurance with contraceptive coverage. Their corporation, Hobby Lobby, would be.

So in September 2012, Hobby Lobby sued the US Department of Health and Human Services, challenging the contraceptive mandate on the grounds that it unconstitutionally and substantially burdens the company’s religious beliefs. The company is asking the court to find that it has the same religious-freedom rights as a church or an individual, a finding no American court has ever made.

“By being required to make a choice between sacrificing our faith or paying millions of dollars in fines, we essentially must choose which poison pill to swallow,” David Green, Hobby Lobby’s founder and CEO, said in a press release when the case was filed. “We simply cannot abandon our religious beliefs to comply with this mandate.”

On many levels, the Hobby Lobby case is a mess of bad facts, political opportunism, and questionable legal theories that might be laughable had some federal courts not taken them seriously. Take for instance Hobby Lobby’s argument that providing coverage for Plan B and Ella substantially limits its religious freedom. The company admits in its complaint that until it considered filing the suit in 2012, its generous health insurance plan actually covered Plan B and Ella (though not IUDs). The burden of this coverage was apparently so insignificant that God, and Hobby Lobby executives, never noticed it until the mandate became a political issue.

The most well-publicized and controversial element of the case is Hobby Lobby’s assertion that a for-profit corporation can have the constitutionally protected right to the free exercise of religion. It’s a strange notion, but the court opened the door to this argument when it ruled in Citizens United that a corporation has First Amendment rights. So now the justices will have to consider whether corporations can pray, believe in an afterlife, and thus, be absolved of ACA’s contraception mandate. But that’s hardly the only thorny issue the court has to grapple with.

For Hobby Lobby to prevail, the company has to, among other things, meet what’s known as the Sherbert test. It requires plaintiffs in religious-freedom cases to first show that their religious beliefs are sincere, and then prove that a government regulation or law poses a substantial burden on those beliefs. Given those criteria, a skeptic might wonder how burdensome the mandate really is for Hobby Lobby when, until just recently, it was mostly in compliance with the law.

The fact that Hobby Lobby once covered the drugs it now objects to is “evidence that these cases are part of a broader effort to undermine the Affordable Care Act, and push new legal theories that could result in businesses being allowed to break the law and harm others under the guise of religious freedom,” says Gretchen Borchelt, senior counsel and director of state reproductive health policy at the National Women’s Law Center.

Motives aside, theoretically the court in Hobby Lobby is being asked to make an entirely subjective judgment as to the sincerity of a plaintiff’s religious beliefs and whether a government regulation poses a “substantial burden” on them. Such things aren’t easily measured, and doing so puts the courts at risk of passing judgment on the religious beliefs themselves, a big constitutional no-no. That’s why back in 1990 the court abandoned the Sherbert test for something more straightforward: Is the law generally applicable or does it single out a specific religious belief for punishment?

In Employment Division v. Smith, the court said it was okay for the state of Oregon to deny unemployment benefits to a couple of counselors at a drug rehab program who’d been fired for using peyote, which was illegal at the time. As members of a Native American church, they argued that denying them benefits violated their right to practice their religion by using peyote. Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote the majority opinion, wasn’t buying it. He wrote that the Oregon law was constitutional because it didn’t single out any particular religious practice. It applied to everyone. He wrote:

The rule respondents favor would open the prospect of constitutionally required religious exemptions from civic obligations of almost every conceivable kind—ranging from compulsory military service to the payment of taxes to health and safety regulation such as manslaughter and child neglect laws, compulsory vaccination laws, drug laws, and traffic laws; to social welfare legislation such as minimum wage laws, child labor laws, animal cruelty laws, environmental protection laws, and laws providing for equality of opportunity for the races.

If Scalia had had the last word on this subject, the court might not even be considering Hobby Lobby. For this case and many of its potentially wide-ranging ramifications we have Congress and Bill Clinton to thank.

The Supreme Court ruling in Smith outraged members of Congress, who in 1993 passed the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (RFRA), which Clinton signed into law. That act forced the court to once again look at things like religious sincerity and to try to measure how much a government mandate burdens any one religious belief—something courts generally don’t like to do. “Courts are wary of scrutinizing sincerity of claims,” says Caroline Mala Corbin, a professor at the University of Miami law school. “They’re worried that it will bleed into judgment of the religious belief itself. And if there’s one thing courts don’t want to do and aren’t allowed to do under the Establishment Clause is to pass judgment about people’s religious beliefs.”

That’s why Corbin thinks the court will steer clear of the sincerity question. Even the government hasn’t touched it. As Lori Windham, a senior counsel for the Becket Fund, which is representing Hobby Lobby, says, “Neither the government nor the courts have disputed the sincerity of the Green’s objections to these drugs and devices.”

But in the Hobby Lobby case, there might be a good reason for the court to take a closer look at whether this legal challenge is politically, rather than religiously, motivated. Not only had the company never objected to covering the kinds of birth control that are now central to its lawsuit, but the reason Hobby Lobby now balks at covering these forms of contraception is based on a false premise—one the court will have to accept as true in order to find in Hobby Lobby’s favor.

The company argues that emergency contraception pills, such as Ella and Plan B, destroy fertilized eggs by interfering with implantation in the uterus. Hobby Lobby’s owners consider this abortion. But the pills don’t work that way. When Plan B first came on the market in 1999, its mechanism for preventing unplanned pregnancies wasn’t entirely clear. That’s why the FDA-approved labeling reflected some uncertainty and said that the pills “theoretically” prevent pregnancy by interfering with implantation. Since then, though, there has been a lot of research on how these pills work, and the findings are definitive: They prevent pregnancy by blocking ovulation. In fact, they don’t work once ovulation has occurred. As Corbin recently wrote in a law review article, “Every reputable scientific study to examine Plan B’s mechanism has concluded that these pills prevent fertilization from occurring in the first place…In short, Plan B is contraception.”

Labels on these products have been updated in Europe to reflect the science, and the Catholic Church in Germany dropped its opposition to local Catholic hospitals providing emergency contraception to rape victims after reviewing the evidence. The science is so clear, in fact, that even Dennis Miller, an abortion foe and director of the bioethics center at the Christian Cedarville University, concluded that emergency contraception drugs don’t cause abortions. Last year, he told Christianity Today. “[O]ur claims of conscience should be based on scientific fact, and we should be willing to change our claims if the facts change.” (IUDs generally work like spermicide, preventing conception.)

Yet the Becket Fund’s Windham insists that the question of the science is not before the court. So basically, the Hobby Lobby case requires the court to decide whether a corporation has sincere religious beliefs that would be compromised by having its health plan cover the contraception that it once covered because it believes that contraception causes abortions, even when it doesn’t. Got that?

Of course, the case isn’t just about Hobby Lobby. The Supreme Court is using it to address dozens of similar lawsuits by other companies that, unlike Hobby Lobby, object to all forms of contraception. But the inconvenient set of facts here are just one reason why the case hasn’t garnered a lot of support outside the evangelical community. Many religious people are uneasy with the idea of corporations being equated with a spiritual institution. At a recent forum on the case sponsored by the American Constitution Society, the Mormon legal scholar Frederick Gedicks, from Brigham Young University, said he was offended by the notion that selling glue and crepe paper was equivalent to his religious practice. “I’m a religious person, and I think my tradition is a little different from an arts and craft store,” he said.

Women’s groups fear a ruling that would gut the ACA’s contraceptive mandate. The business community, meanwhile, doesn’t want to see the court rule that a corporation is no different from its owners because it would open up CEOs and board members to lawsuits that corporate law now protects them from, upending a century’s worth of established legal precedent.

No one seems to really have a sense of how the court might rule. On one side, court watchers have speculated that with five six Catholics on the bench, Hobby Lobby has a decent shot of prevailing. But then again, one of those Catholics, Chief Justice John Roberts, is also sensitive to the interests of corporate America. He seems unlikely to do anything that might disrupt the orderly conduct of business in this country and make the US Chamber of Commerce unhappy, as a victory for Hobby Lobby could. Scalia is an ardent abortion foe, but his view of Native American peyote users might incline him to find for the government.

Finding a reasonable way out of this case won’t be easy. The litany of bad outcomes has some legal scholars rooting for what might be called “the Lederman solution“—a punt. Georgetown law professor Martin Lederman has suggested that the lower courts have misread the contraceptive-mandate cases by assuming firms such as Hobby Lobby have only two choices: provide birth control coverage or pay huge fines to avoid violating their religious beliefs. He argues that while the ACA requires individuals to purchase health insurance, it doesn’t require employers to provide it. If companies choose to do so then the insurance companies must cover contraception without co-pays. Hobby Lobby and the other companies currently suing the Obama administration can resolve their problems by simply jettisoning their health insurance plans and letting their employees purchase coverage through the exchanges.

An employer that drops its health plan would have to pay a tax to help subsidize its employees’ coverage obtained through the exchange or Medicaid, but this option is actually far cheaper than providing health insurance. And if a company doesn’t even have to provide insurance, much less a plan that covers contraception, Hobby Lobby doesn’t have much of a case that the ACA burdens its free exercise of religion.

Lederman’s analysis gives the court an easy out in Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby, allowing it to avoid the dicey questions of whether corporations have religious-freedom rights, whether scientific ignorance is a religious belief—or even whether the plaintiff is sincerely religious or simply part of a larger Republican-led political effort to kill off Obamacare.