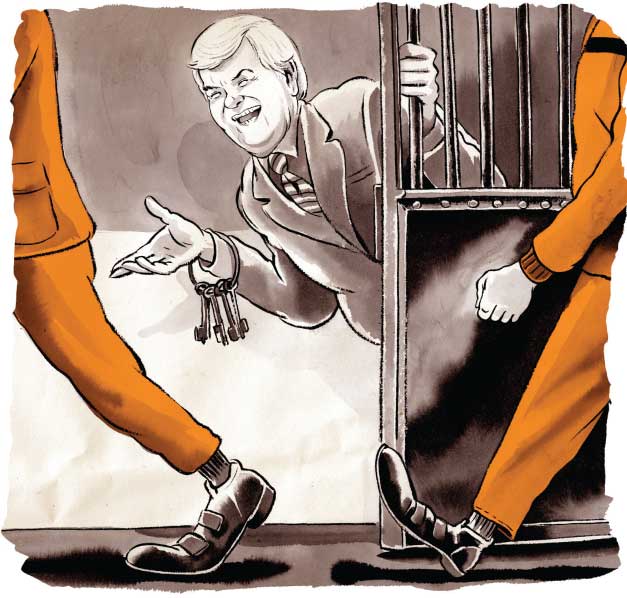

In the early 1990s, then-Rep. Newt Gingrich unveiled one of the centerpieces of his new conservative agenda: putting more Americans behind bars. More prisons were urgently needed, he told the New York Times in 1992, “so that there are enough beds that every violent criminal in America is locked up, and they will serve real time and they will serve their full sentence and they do not get out on good behavior.” Finding the money for more cells was as easy as stripping “pork” from the budget. In the meantime, decommissioned military bases could house excess inmates. The Georgia Republican’s 1994 “Contract With America” included the Taking Back Our Streets Act, which would fund more state prisons, with extra money for states that curtailed parole.

Over the next two decades, the prison population more than doubled. One in 200 Americans is behind bars, the highest incarceration rate in the world. In 2009, the nation spent $82.7 billion on corrections, a 230 percent increase from 1990.

Today, Gingrich has changed his tune. “There is an urgent need to address the astronomical growth in the prison population, with its huge costs in dollars and lost human potential,” Gingrich wrote in a 2011 op-ed in the Washington Post. “We can no longer afford business as usual with prisons. The criminal justice system is broken, and conservatives must lead the way in fixing it.”

Gingrich is one of many high-profile conservatives to embrace criminal-justice reforms that would have been unthinkable in Republican circles just a few years ago. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie has vowed to end “the failed war on drugs that believes that incarceration is the cure of every ill caused by drug abuse.” Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) says the court system “disproportionately punishes the black community” and insists on repealing mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes. Others who have spoken in favor of less draconian criminal policies include former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, former National Rifle Association President David Keene, former Attorney General Edwin Meese, former DEA head Asa Hutchinson, and Americans for Tax Reform founder Grover Norquist.

The roots of this shift can be traced to a mild-mannered Texas attorney named Marc Levin, who has become one of the nation’s leading advocates of conservative criminal-justice reform. Levin saw the light in 2005 when a board member of the free-market-oriented Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF), where he worked, told him, “We’re not getting a good return for our money out of our prisons.” Looking at the state’s prison buildup under governors Ann Richards and George W. Bush, Levin drew the same conclusion. “Once you reach a certain rate of incarceration, you start to have diminishing returns because you aren’t just putting dangerous people in prisons anymore,” he says. “You are putting in nonviolent offenders. You are not really impacting crime. You are not making people safer.”

For a fiscal conservative, this was a compelling argument for change. “How is it ‘conservative’ to spend vast amounts of taxpayer money on a strategy without asking whether it is providing taxpayers with the best public safety return on their investment?” Levin asks. Rather than spend a fortune keeping low-risk offenders in prison, Levin proposed that the same money could be used for cheaper programs that would still keep violent criminals locked away and the public safe.

So in 2007, when Texas moved to add more than 17,000 prison beds at a cost of around $2 billion, Levin and the TPPF suggested another option: spending an eighth of that money on drug courts and rehabilitative programs for addicts and mentally ill prisoners. Legislators and Gov. Rick Perry signed on. Since then, Texas’ incarceration rate has fallen nearly 20 percent, a decline attributed in large part to these programs. (Nationwide, the incarceration rate has fallen almost 5 percent since it peaked in 2009.) Meanwhile, Texas’ crime rate is at its lowest since 1968. A recent poll showed that 81 percent of Texan Republican voters support treatment rather than prison for drug offenders.

In 2010, Levin formed an organization called Right on Crime and began reaching out to conservative think tankers and state legislators around the country. His bottom-line approach began to take hold—or at least shield reformers from being labeled soft on crime. Since then no fewer than 58 correctional facilities have closed across the nation; around two-thirds of the decommissioned beds were in states with Republican governors. Between 2006 and 2012, Wyoming, Michigan, and Utah—all GOP-dominated—reduced their incarceration rates (excluding jails) by more than 10 percent. Under Republican Gov. Haley Barbour, Mississippi saved $5.6 million in 2010 by closing down the isolation unit in one of its supermax prisons, letting nearly 1,000 prisoners out of solitary.

“Right on Crime has done a tremendous job of framing the need to end this country’s addiction to incarceration in a way that conservatives are now increasingly buying into,” says Vanita Gupta, deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union. Yet Levin is quick to note that he doesn’t see eye to eye with liberals, who he says emphasize the rights of offenders at the expense of victims and don’t appreciate the need for serious penalties. “We think you need both the carrot and the stick,” he says. “I think some people on the left like the carrot part. They don’t like the stick part.”

One of Right on Crime’s main targets is parole. Researchers have found that parole drove 60 percent of the rise in the prison population in the 1990s. In some states, more than half of all parolees sent back to prison had only minor, nonviolent violations, like missing meetings with their parole officers. At least 11 Republican-leaning states have eased penalties for parole violations since 2006.

Right on Crime has also taken on mandatory minimums, laws that require certain crimes to be punished by a predetermined sentence regardless of any mitigating factors. In 2010, South Carolina eliminated mandatory minimums for many nontrafficking drug offenses. Within a year, its incarceration rate dropped nearly 4 percent. Even the American Legislative Exchange Council, the conservative group that helped propagate mandatory minimum laws in the ’90s, is now backing a bill, written in part by Right on Crime, that grants judges the discretion to depart from mandatory minimums for some nonviolent offenses.

Last August, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that federal prosecutors would no longer pursue mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenses.* “There’s no doubt in my mind,” says Gupta, that conservatives’ new enthusiasm for reform helped give Holder the political cover to make this decision. Richard Viguerie, a major figure in the Moral Majority and the head of the tea party website ConservativeHQ, mocked Holder’s “belated” announcement and welcomed him “to join the cause of criminal justice and prison reform that conservative governors and legislators have been leading.”

Indeed, these days Right on Crime supporters are sounding more progressive on criminal-justice issues than some Democrats. “What is frustrating is that now that conservatives have started to adopt corrections reform and reducing incarceration as a conservative issue, more Democrats have not become more emboldened to call for the same thing,” Gupta says.

Take California’s Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown, who has tried to resist a federal court order to reduce his state’s swollen prison population by transferring inmates to private prisons rather than releasing nonviolent offenders. Last summer, he vetoed a bill that would have reduced sentences for possession of small amounts of drugs, in contrast with at least 11 Republican governors who have enacted similar reforms. Right on Crime had pushed for the bill, but in such a solidly blue state, there was only so much Levin could do.

Prison blues (and reds)

Change in states’ prison populations, 2006-12. Party designates most dominant party in legislatures and governorships during that time.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2006, 2012)

Red states’ dominant legislature and governorship were controlled by Republicans at least 50 percent of the time between 2006 and 2012; blue states’ dominant legislature and governorship were controlled by Democrats at least 50 percent of the time between 2006 and 2012. Source: Washington Post

Correction: This article originally stated that Attorney General Holder lifted mandatory minimum sentences for all offenses. They remain in place for high-level and violent drug crimes.