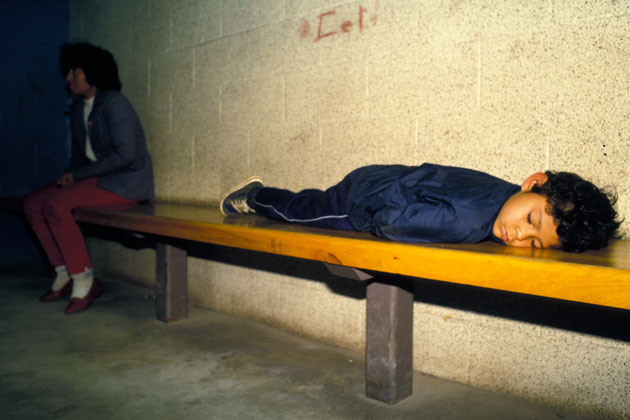

Tom Ervin/ZUMA

Audelina Aguilar set off on the six-week journey along the migrant trail at 14, leaving her parents and nine younger siblings behind in the highlands of rural Guatemala. She rode atop Mexican freight trains, from Chiapas in the south to Tamaulipas in the north. She fought off a would-be rapist with the help of the only other woman in the group, who screamed, “She’s a baby!” She walked through the South Texas wilderness for four days, trying to steer clear of the assailant, who was still with the group, and of the human remains they encountered along the way.

They were led by a coyote, and her 16-year-old cousin was with her, but other than that Aguilar was on her own. “When I left my country,” she told me, “I said, ‘I know God is going to be with me, and everything is going to be okay.'”

Eventually Aguilar made it to San Francisco, where her 16-year-old brother lived. They stayed with an aunt, but soon moved out, not wanting to burden her. Aguilar went to work to pay back another aunt in Alabama who’d handled her smuggling fee, first as a babysitter and later on the crews that clean huge hillside homes with views of the bay. She usually got bathroom duty. Hardly anyone asked why she wasn’t in school.

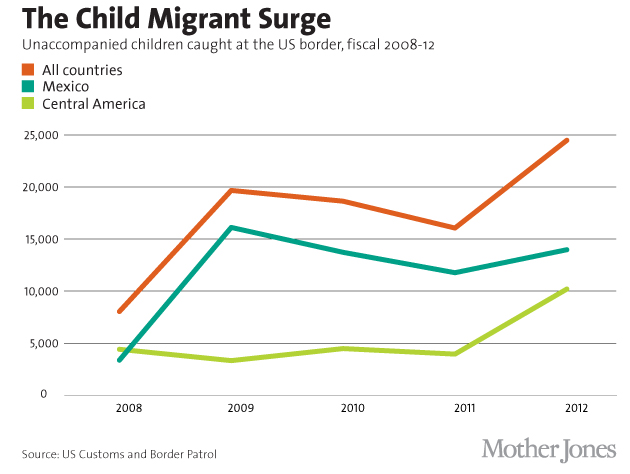

Her journey is not unusual. Over the past five years, the number of undocumented children—mostly teens, but some as young as five—apprehended crossing the border without parents or guardians has tripled, rising from 8,041 in fiscal year 2008 to 24,481 in fiscal 2012, with a 52 percent increase from 2011 to 2012 alone. Countless others, including Aguilar, made the trip without getting caught.

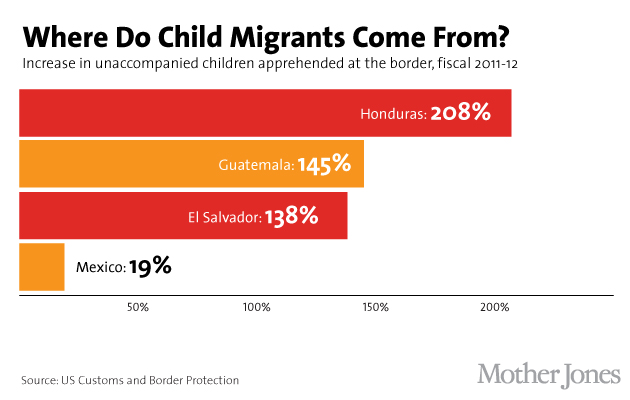

A major factor in the increase, known simply as “the surge” to government officials and child-welfare advocates, appears to be the rise in gang violence in Central America. The number of Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran children crossing alone has skyrocketed in recent years, even as the number of Mexican kids has held steady. “What’s alarming is that there’s an increasing number saying they’re fleeing forcible gang recruitment and gang violence,” says Elizabeth Kennedy, a San Diego State University researcher who studies unaccompanied child migrants. “They were being forcibly recruited into the gangs and didn’t want to be a part of it, and so they had to flee because threats had been made on them or their family members.”

That’s exactly what happened to two of Aguilar’s younger brothers back in their hometown of La Cumbre; one came to the United States last year, at 17, while the other, 16, crossed the border a couple of months ago. As the authors of a 2012 Women’s Refugee Commission report (PDF) on the surge wrote, “Until conditions for children in these countries change substantially, we expect this trend will be the new norm.”

Still, unaccompanied children barely register in the national immigration debate, where most of the talk about youth has focused on the DREAM Act, the proposed legislation that would legalize some undocumented immigrants brought to the country as kids. (It would require five years of residency and a high school diploma, disqualifying most of these more-recent migrants.) Legal-aid groups have pushed reforms such as government-appointed lawyers for unaccompanied children. Many of them, advocates note, actually qualify for asylum or other legal relief, but will never know it because they don’t have legal representation.

When apprehended, kids trying to cross the border are treated differently than adults: Instead of being placed in immigration detention, they are turned over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services. While seeking to reunify the kids with US-based family during their deportation proceedings, ORR puts them up in shelters run by nonprofit subcontractors like Catholic Charities. (When I first met Aguilar in September, her brother had just left Guatemala; the second time we spoke, he’d just been caught; the third time, recently, he’d just arrived in San Francisco after his stay in an ORR facility.)

Journalists aren’t allowed into the shelters “for safety reasons,” an ORR spokeswoman told me. But Susan Terrio, a Georgetown University anthropologist currently writing a book about unaccompanied children, visited 19 of them over a four-year period. She says she was surprised to find an almost hermetically sealed system: “The kids were never left unattended. They went to school inside, they played sports inside, and they only got out for supervised outings in the community or for medical and mental-health appointments.”

Maria Woltjen, director of the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, says that as a result, unaccompanied children are essentially invisible: “Nobody in Chicago knows there are 400 kids detained in our midst. They’re just in [former] nursing homes—you walk by, and you think it’s just an old nursing home, and it’s actually all these immigrant kids inside.”

While many child-welfare advocates are hesitant to criticize the ORR facilities for fear of being shut out of them, the shelters did come under scrutiny in 2007, when ORR removed kids from a Texas facility after a female guard was accused of sexually assaulting four minors. (She was later convicted.) In the summer of 2012, lacking enough beds to deal with the influx of Central American children, ORR temporarily housed hundreds in emergency dormitories at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. According to the Women’s Refugee Commission report, “the facility looked and felt like an emergency hurricane shelter with cots for beds and portable furniture.” (The base no longer houses children.)

In fiscal 2011, ORR had 53 shelters that housed 6,560 kids. In 2012, those numbers increased to 68 and 13,625; in 2013, there were 80 shelters and 24,668 unaccompanied children. The majority are in states along the Mexican border, hours from big cities, which means it’s even harder for kids to find legal representation—and stave off being sent back to the dangerous situations they fled.

ProBAR, a pro bono project that specializes in representing unaccompanied children, is based in the South Texas border city of Harlingen, a half hour west of Brownsville. When I visit its office in mid-December, I meet with managing attorney Kimi Jackson, who says the number of beds ProBAR serves jumped from 369 in September 2011 to 1,187 in September 2013.

Jackson says the government has been reunifying unaccompanied kids with family members faster than ever before—the average shelter stay has fallen from 72 days in 2011 to 45 days. That’s good for the kids, but it has complicated ProBAR’s work: It means less time to tell them about their rights and screen them about their experiences to build a case against deportation. “We are not able to provide the same services that we used to, because there just isn’t time,” Jackson admits.

So ProBAR’s paralegals go in groups to give their presentations and screen hundreds of kids at a time, listening to countless heartrending testimonials. The attorneys scour their notes, trying to decide whom to represent and whom to refer to other nearby pro bono lawyers. “I can only read so many of them in one sitting,” Jackson says, “because it’s emotionally exhausting.”

And even after unaccompanied kids link up with family members, they’re still vulnerable—to abuse, to trafficking, to exploitation by employers. After two years of working full time, bringing home as little as $25 a day after transportation costs, Audelina Aguilar ended up in the hospital one day with severe abdominal pain. The nurses told her she had an ovarian inflammation; when they found out that her parents were back in Guatemala, they made the teen swear that she’d stop working and enroll in school.

That’s how she landed at SFIHS. Now in its fifth year, it’s a public alternative school in the Mission District that serves recently arrived immigrants. Some are fleeing a civil war. Others endured traumatic border crossings or time locked up in immigration detention. The vast majority, says Principal Julie Kessler, are suffering from some form of PTSD.

She estimates that roughly 20 percent of her students came alone. They live in shelters or group homes, or have figured something out with a relative, or live by themselves. “They are absolutely the most resilient, wonderful, resourceful, and motivated group of kids that we have,” Kessler says.

That’s Aguilar. After enrolling in school, a lawyer at Legal Services for Children helped her become a legal resident. Her older brother started working, allowing them to move into a studio apartment by themselves. She only spoke Spanish when she started at the school as a ninth-grader; now, at 20, she talks to me almost exclusively in English—about missing the Mayan skirts she left behind in Guatemala, about the stress of being the de facto mother to her three brothers, about balancing schoolwork with her new job at Old Navy.

In the last month Aguilar has finished up applying for colleges—the University of California-Berkeley is at the top of her list—and received a prestigious scholarship for economically disadvantaged students. Still, there’s the thousands of dollars she borrowed to pay for the passage of the brother who just arrived, as well as the money she’ll need to get him an attorney. And there are seven more siblings, and her parents, to think about back home in La Cumbre.

“We don’t have Dad and Mom to take care of us,” she says. “If we need something, we don’t have that. We just have to wait until we have what we want.”

This project was made possible by a fellowship from the French-American Foundation—United States.