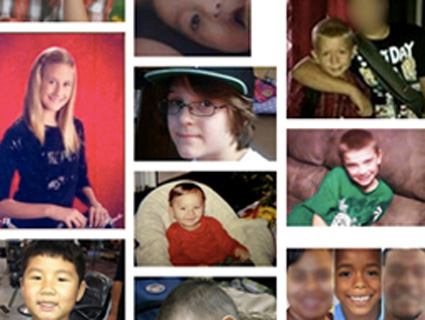

Superintendent Matt Dossey launched a program to arm a select group of staff at the Jonesboro Independent School District in central Texas. Nicholas Kusnetz/Center for Public Integrity

This story first appeared on the Center for Public Integrity website.

It wasn’t quite cold enough to need a vest on a recent Texas morning, but Matt Dossey was wearing one anyway. Made of heavy canvas, the vest might have concealed a pistol. There was no way to tell. Perhaps that was the point.

Dossey is superintendent at Jonesboro Independent School District, which serves a tiny community in the rolling Texas scrubland north of Austin. In January, the district decided to arm a select group of staffers with concealed weapons.

Jonesboro straddles the border between Coryell and Hamilton counties; it’s more than 15 miles to the nearest sheriff’s department. The town is unincorporated, and has no government or police. If someone were to attack the school, Dossey said, no one’s coming to protect the kids—not quickly, anyway.

Dossey was standing inside the school cafeteria, where students motored around a room decorated with harvest-themed paper cutouts. The district was hosting a pre-holiday Thanksgiving dinner, when parents join kids for a school lunch of turkey and stuffing. Looking around the room, Dossey, who hadn’t taken off his vest, said the new policy adds a layer of security that most everyone in town is happy with.

“If somebody walked in that door and opened fire,” he said, “we would have a chance.”

Ever since Adam Lanza killed 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, last December, school districts and state governments have searched for better ways to protect students. Lawmakers introduced hundreds of school safety bills. Many called for arming more security guards or for arming teachers. Others went the opposite direction, tightening gun laws.

In Monroe, Connecticut, just nine miles from Sandy Hook, residents supported a range of expensive measures. The town, which spreads out from a village green between two white-steepled churches, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars upgrading buildings and hiring school resource officers, town cops who are posted at schools. The move is largely in step with what happened statewide. Lawmakers passed sweeping legislation in April that included gun controls, such as expanded background checks and mandates for school security. The Legislature also funded millions of dollars in infrastructure grants and tightened state law covering guns in school so that only active or retired law enforcement officers can serve as armed guards.

Texas, on the other hand, has not appropriated money to school security and is not creating mandates. Jonesboro is one of about 70 districts to arm staff since Sandy Hook. This year, the Legislature encouraged more to do the same, passing a bill that created a state-run training program that will allow districts to designate staff as “school marshals,” an entirely new class of law enforcement (districts must pay the costs).

At first glance, the disparate approaches appear simply to reflect a stereotypical divide between two regions of America with their own closely held views of guns and their place in daily life. But a closer look shows that what’s happened in Jonesboro and Monroe also reflects a broader set of beliefs about the role of government, about local control, and perhaps most importantly, about taxes.

A Flurry of Activity

Just after 9:30 a.m. on December 14, Lanza, 20, arrived at Sandy Hook Elementary School armed with a Bushmaster rifle and two pistols. Staff had just locked the front door, but Lanza shot his way through the entranceway glass. Down the hall, the principal, school psychologist and another staff member heard the shots and came to investigate. Lanza shot all three, killing the principal and the psychologist, before making his way to two first-grade classrooms, where he killed the children and four adults.

A staff member had called 911 at 9:35 and police arrived within four minutes. Within a minute, Lanza shot himself. The entire episode lasted no more than 11 minutes, according to a recent report by the local state’s attorney (PDF).

Residents and victims’ families soon formed groups, some supporting stricter gun controls. Several parents created Safe and Sound, an organization that offers tools for districts to improve security through planning and training.

In Washington, much of the debate focused on guns. Wayne LaPierre, executive vice president of the National Rifle Association, called on Congress to fund an armed police officer in every school. “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” he said.

President Obama announced a broad plan in January encompassing gun control and school security. But his signature initiative, calling for background checks on most gun sales, died in the Senate in April. The security measures fared better. The Justice Department gave $46.5 million in grants in the 2013 fiscal year to fund 370 school resource officers, who are being stationed in schools nationwide. Districts have added thousands of such officers on their own, said Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers—augmenting the 10,000 or so already in place. In June, the Education Department published a how-to guide for schools to create emergency plans.

But federal funding for several school safety programs has dropped steadily since receiving a boost in 2009. The COPS program, which pays for community police efforts including school resource officers, saw funding cut by more than 80 percent, to $178 million in fiscal year 2013, for example.

State legislatures have acted as well. Lawmakers sponsored bills on school safety in every state, introducing more than 500 this year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Dozens became law.

While most focused on emergency planning or safety grants, South Dakota in March became the first state to explicitly allow schools to authorize their staff to carry guns. Lawmakers introduced similar bills in 34 states, according to NCSL, passing them in six others. In several states, including Colorado, Oregon, and Ohio, districts have used existing laws to arm staff.

Nearly every state generally bars guns from school grounds, but many give districts some wiggle room. Texas, for example, has for years allowed schools to authorize people to carry weapons on campus. Other state laws are open to interpretation. But few if any districts had armed teachers before Sandy Hook, other than one in rural Texas.

Over the past few years, however, gun groups began pushing to expand the exceptions, according to the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. In April, an NRA panel published a model bill for states that would allow districts to make their own decisions on arming staff. The organization did not respond to an interview request.

A Different Culture

Matt Dossey stands tall with a genial demeanor, and at 40, he’s as close as Jonesboro has to a town leader, serving not only as school superintendent, but also as minister at the Baptist church. Dossey grew up in Gatesville, about 15 miles southeast. And aside from attending college in Abilene, he’s spent practically his whole life within a 15-mile radius. His wife, Emily, and mother, Mildred, each graduated from Jonesboro High School. His older son, who’s 6, attends the kindergarten.

He’s not the only one to stay close to home. Standing in the cafeteria, he could point to the children of his childhood friend, or to a young teacher who was his student years ago. While the small-town feel engenders trust, he said it makes securing the school a maddening task. Parents expect to go where they please. Closing doors isn’t foremost on kids’ minds.

Dossey had first proposed the idea of arming teachers to the school board after he came to the district in 2011, citing Harrold, a rural district in north Texas that adopted a similar plan in 2007. Some board members were hesitant. “Anytime you put weapons in an atmosphere where you’ve got a bunch of kids, you’ve got to be careful,” said Keith Taylor, president of the school board.

Sandy Hook convinced Taylor and other trustees that it was worth that risk. On January 17, all seven members voted to adopt the plan.

“We live in a place where our kids are familiar with guns,” Dossey said, describing how students camp out with their guns by the football field each summer, when irrigated grass creates a green oasis amid the dry landscape. “Armadillos love to come to our football field and dig up holes rooting for worms and grubs. Well, our kids go down there armadillo hunting,” he said. “It’s a different culture out here. Everyone has guns in their home, if not for skunks or whatever, then for intruders.”

Despite the culture, some have resisted arming teachers. Most of the state’s larger districts have their own police departments and have said they will not arm other staff. In Austin, district police hired six school resource officers this year to patrol the city’s 79 elementary schools—they already had officers at each high and middle school.

Bill Bond, school safety specialist for the National Association of Secondary School Principals, doubts that an armed teacher would actually stop a student bent on killing peers. He was the principal at a high school in West Paducah, Kentucky, in 1997 when a student killed three classmates. “I don’t believe a teacher would just kill a kid right there,” he said. “I’ve walked up in front of a kid who had a gun. I know how it feels. I think you’d hesitate.” More likely, he said, is that an armed teacher would lead to a deadly accident.

Law enforcement groups have spoken against arming school staff. Several have said that police could accidentally shoot a teacher holding a gun. Some insurers, such as EMC Insurance Companies, which covers most Kansas districts, have said they would decline coverage to any school that allows employees to carry guns.

Dossey has seen little of this opposition and speaks of his program in a confident tone. He and the board selected a few staff members for the program before buying them firearms and tapping the local sheriff to help with training. The district has kept their identities secret. Members of the program get together once a month for target practice.

The school district is also replacing old doors and installing a buzzer system for the front entrance, which is now unlocked. The work will cost about $50,000, Dossey said, and will come out of a broader $700,000 bond that voters approved in May. Dossey says arming a few staff will cost about $8,000 this year, compared to at least five times as much for a resource officer.

In 2011, the state legislature cut the education budget by more than $5 billion. While lawmakers restored about $3.3 billion this year, those cuts continue to loom large.

But even though Dossey would rather hire a school resource officer if he had more money, he told his state representative that he opposed a bill that would have allowed districts to levy taxes to pay for security measures, including the hiring of resource officers. Taxes are not popular in Texas. The bill never saw a vote.

Linda Bridges, president of the Texas affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers, opposes arming teachers, and she’s skeptical of districts’ claims that they don’t have the money to hire a resource officer. “The issue really is, what are the priorities?” she said.

Bridges and other teachers’ advocates say the push in the capital for arming teachers was as much about politics as it was about safety. Within weeks of the Sandy Hook shooting, Gov. Rick Perry voiced support for allowing more guns in schools. Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst went further, calling for state funding to train teachers to carry guns (Perry later vetoed a bill that would have provided up to $1 million for this, citing several shortcomings, including the cost).

“I didn’t hear him talking about how we make our schools better,” said Ken Zarifis, president of Education Austin, the city’s main teachers union. “The first thing I heard out of Lt. Gov. Dewhurst’s mouth was about how we train teachers to carry guns. Well, welcome to Texas.”

Safety Trumps All

Nearly 2,000 miles away, Superintendent James Agostine is operating under different circumstances. Sitting at his desk in Monroe Elementary School, a two-story building perched on a rise above the Monroe Turnpike, Agostine can monitor dozens of security cameras across the district’s five schools, with the images neatly organized on one of two monitors connected to his computer. The cameras are part of a technology upgrade the district purchased after the shooting in neighboring Newtown. The district also installed new door locks in many classrooms, replaced outer doors and added two school resource officers to the two it already had.

The district installed double-sets of doors to the schools’ front entrances, so visitors must now get buzzed through consecutive locked doors, a level of security more common at banks. In case of an incident, the receptionist can now hit a red panic button that dispatches police to the school.

No one needs a reminder of what happened nearby. The Monroe district, in a heavily wooded community in southwestern Connecticut, is housing Sandy Hook Elementary at one of its buildings while Newtown builds a new school. And Agostine, dressed in a checked shirt and tie, seems to have embraced the role of protector.

“In my career, the top priority is safety,” he said. “Safety trumps all.”

Over the past year, Monroe has spent nearly $815,000 upgrading security at its schools, leaning heavily on those infrastructure changes. Like the state as a whole, Monroe can afford to spend more than most—median income here is about $108,000.

In April, the Legislature in Hartford passed some of the country’s tightest gun controls—requiring background checks on all gun sales and expanding the list of banned assault weapons—along with a handful of school security measures. Lawmakers and the governor created panels and commissions on everything from mental health to security, including the School Safety Infrastructure Council, which is expected to release recommendations in January that will eventually be required as part of any state-funded school construction. In the meantime, the state has spread $21 million in grants across two-thirds of its districts, helping them upgrade facilities. Many districts added school resource officers, but no one talked seriously of arming teachers.

There’s a powerful sense of before and after in Connecticut (school administrators refer to the day, like 9/11, by its date, 12/14). “It’s becoming not only more acceptable but more of a public demand for security in schools,” said Donald DeFronzo, commissioner of the state Department of Administrative Services and chairman of the School Safety Infrastructure Council. “Parents want to believe that when they drop their kids off in the morning that they’re leaving them, next to home, in the most secure place anywhere.”

DeFronzo said the council is working with the federal Department of Homeland Security to adapt a security assessment tool now used for federal buildings. Rather than prescribe blanket fixes, the tool will help districts identify security weaknesses while suggesting a range of corrective measures.

All this will come with a cost. DeFronzo said the requirements could add up to 15 percent to any given construction project. Connecticut schools have spent about $530 million a year on school construction over the past five years, with the state covering more than two-thirds of that. New security measures could tack on tens of millions of dollars annually. While the state budget office expects a surplus for the next two years, it recently projected a deficit of $1.1 billion for the year beginning July 1, 2015.

While Monroe did not apply for state grants, the district was lucky. Administrators had already been looking at security upgrades before the shooting, and were prepared to spend part of the regular maintenance budget. Savings on medical expenses last year allowed them to devote an additional $240,000 to the work. They hired consultants, attended conferences, updated their emergency plans (the new law includes requirements for these plans). The preparation meant the district was ready to move immediately.

“Within months of Sandy Hook happening, everybody is getting busy,” Agostine said. “You can’t find a contractor now to come in and design a new system. They don’t have the horses in the stall.”

Still, the town of nearly 20,000 didn’t avoid debate over the costs. In April, voters rejected an annual budget that included funding for three new school resource officers. After some residents questioned the need for additional officers, the town cut one of the positions from the budget, which was then approved in a subsequent referendum.

Agostine seems comfortable speaking about the security measures, some of which began before the shooting, but he acknowledges they come with a social price, too. “Years ago it would not be uncommon for a parent to come in with their child, walk down to the classroom, help the child at their locker, give them a kiss and send them into the classroom. Now we say, ‘Leave them at the door,’ ” he said. Later, Agostine compared their work to the broader security measures Americans experience, like near-constant surveillance. “The cost of our society in terms of security is that we give up a little bit of that autonomy.”

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit, independent investigative news outlet. For more of its stories on this topic, go to publicintegrity.org.