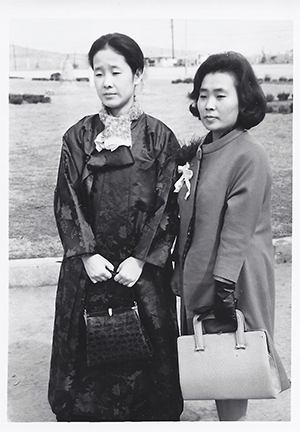

Sam Park (left) with the Pak familyCourtesy of Samuel Park

When the Washington Times threw its 20th anniversary gala in 2002, conservative luminaries lined up to pay tribute, including Ronald Reagan, who addressed the packed ballroom via video. Afterward, the paper’s enigmatic founder, the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, took the podium. “Even before the term ‘family value’ became a popular phrase, every day of the week the Times was publishing articles highlighting the breakdown in values and what must be done to return to a good, moral society,” he said, through a translator. “Today, family values have become an essential piece of the social fabric in America, even becoming part of the political landscape. We can be proud of the Washington Times‘ contribution that promoted and elevated family values to an essential part of society in America and the world!”

Moon, the founder of the South Korea-based Unification Church, which had hundreds of thousands of adherents at its peak, claimed to be on a divine mission to salvage humanity by rebuilding the traditional family. Before his death last year at age 92, the self-proclaimed messiah—who was known for marrying off his followers in mass weddings—presided over a multibillion-dollar business empire. And he plowed huge sums of money into politics, launching a vast network of media outlets and front groups that promoted conservative family values and left a lasting mark on the modern-day GOP.

But this family values crusader harbored a secret. While he was promoting marriage as the solution to society’s woes and inveighing against “free sex,” his personal life was full of philandering—including at least one adulterous relationship that produced a son. To hide the boy’s identify from his followers, Moon instructed his right-hand man, who was also the founding president and publisher of the Washington Times, to raise the child. Moon’s illegitimate son, Sam Park, who is now 47 years old and lives in Arizona, also helped guard his father’s secret, by staying silent. Until now.

Park, who has shaggy salt-and-pepper hair and a mellow demeanor, resides in Phoenix with his 77-year-old mother, Annie Choi. Their story, which I touched on in a recent article about the unraveling of Moon’s empire in The New Republic, casts a spotlight on the hidden history of Moon’s church, a strange but influential institution that has maintained close ties to the Republican Party since the Reagan era.

Choi says the initiation rites for early female disciples involved having sex with Moon three times. She also alleges that Moon kept a stable of a half-dozen concubines, known as the Six Marys.

Choi joined Moon’s church along with her mother and sister in the early 1950s. At the time, the family lived in the southern Korean city of Pusan. Moon had fled there after escaping a communist labor camp in North Korea, where he was imprisoned, reportedly on bigamy charges. Initially, he had only a few dozen followers, who met in a two-room house on the outskirts of town and were expected to sacrifice everything for the church. For young female members, this included their virginity. Choi says the initiation rites for early female disciples involved having sex with Moon three times. She also alleges that Moon kept a stable of a half-dozen concubines, known as the Six Marys, and inducted her into the group when she was 17. Sometimes, she adds, he would assemble them all in a circle and take turns mounting them. Choi’s account is consistent with those of other early followers, who claim that Moon’s church began as an erotic cult, with Moon “purifying” female followers through sexual rites. (One former acolyte published a book on the topic in Japan.)

According to Choi, Moon persuaded her mother, whose husband owned one of Korea’s largest insurance companies, that their family played a special role in God’s plan: Just like Jacob, who married two women and had children by them and their handmaids, Moon would marry both of her daughters, and they would give birth to the world’s first sin-free children. Choi’s mother was so devoted to this vision that in 1954 she sold one of the family’s homes and gave the proceeds to Moon. Soon thereafter, he opened a church in Seoul and his movement began to flourish. By 1959, more than 30 churches had sprung up around Korea, and Moon’s teachings started to spread to other countries.

But that year Moon’s marriage plans hit a snag, when Choi’s older sister abandoned the church and broke off the engagement. Rather than marry Choi, in late 1959, Moon, who was then 40, began casting about for another bride. He quickly settled on his cook’s daughter, a shy 17-year-old girl named Hak Ja Han. After their wedding in early 1960, Moon—whose church was rapidly expanding into the United States—began teaching that marriage was the key to salvation. He and his new wife would create the “prototype of the perfect family” and give birth to sin-free children. Followers could join his sinless family by keeping themselves chaste until Moon married them off in one of his now-famous mass-wedding ceremonies and then building strong, faithful families of their own.

During this era, Moon preached that sex outside of marriage was the worst possible sin. But Choi and other insiders allege that Moon’s philandering continued long after his own marriage. Choi says she kept having sex with him regularly until 1964, when she moved to the United States to attend Georgetown University, in Washington, DC. Prior to her departure, Choi claims, she and Moon were married in a secret ceremony at his church. The following year, Moon made his first trip to the United States and stayed for several months with his deputy, Bo Hi Pak, near the nation’s capital. During the trip, he spent a good deal of time with Choi. (One photo from the era shows the two of them and Pak huddled in front of the Washington Monument.) Before long, Choi was carrying Moon’s child.

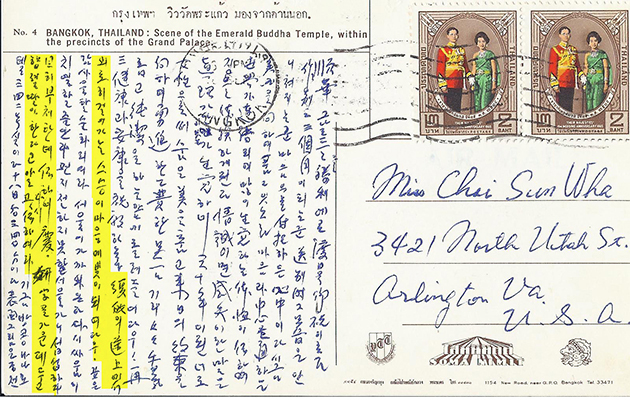

This news could have destroyed the fledgling American movement, but Moon and Pak made sure that didn’t happen. Choi says Moon instructed her to hide her pregnancy and give the child to the Pak family to raise. As he traveled Asia and Europe over the next few months, Moon sent Choi a string of tender postcards, praising her “noble heart” and giving additional instructions, including what to name the baby: “Deliver the message to Bo Hi [Pak] and his wife to use Kyung.”

According to Choi, the Paks, who already had five children, pretended they were expecting another. Mrs. Pak stuffed her midsection with an expanding mound of cloth diapers to mimic pregnancy. When Choi went into labor, Pak drove her to a Washington, DC, hospital and passed her off as his wife. The Paks were even listed as the child’s parents on his birth certificate. (Lawyers for Bo Hi Pak and his wife, who now live in Korea, did not respond to interview requests.)

After the birth, Pak dropped Choi off at her apartment and took the baby to his family’s home in northern Virginia. It was a snowy day. Choi, who still believed Moon was the messiah, recalls her small apartment feeling vast and empty, as she sat weeping into her soup. “I asked myself, what am I doing?” she recalls. “But then I reminded myself: I was born for this mission. My personal dreams are no big deal.”

Choi stayed in the United States to be near her son, who was born Samuel Pak, but went by Jin Kyung (a combination of the name Moon requested and the character “Jin,” often used in Moon family names) or the American name Sam Park. At the time, not even the Pak children knew Sam was not their biological brother.

Choi dropped by periodically and lavished the child with affection. When Park was in elementary school, she also began inviting him for dinners and sleepovers at her place, a colonial-style townhouse on a quiet Northern Virginia cul-de-sac. But Moon took pains to distance himself from Park. While he regularly visited the Pak home, especially after moving to the United States in 1971, he avoided conversing with the boy. “He never asked me anything: How old are you? How’s school going?” Park recalls. “It was as if he was making a point of not showing an interest.”

Along with raising Moon’s son, Bo Hi Pak—a former Korean military officer with Korean Central Intelligence Agency ties—oversaw much of Moon’s US empire, and promoted the Korean messiah’s grandiose goals of vanquishing communism and uniting all nations and faiths under Moon’s dominion. Pak was founding president and publisher of the Washington Times, which launched in 1982. He also headed Unification Church International (now UCI), the holding company for a constellation of Moon-owned companies that were collectively worth billions. And he directed several of Moon’s influential political groups, including CAUSA International, which aided anti-communist rebels in Latin America and promoted Moon’s theology as an antidote to communism among congressional staffers.

When Park was about 13, Choi finally told him who his parents were. “When she said it, it made so much sense,” Park recalls. “Of course, she’s my mother! How could I not have seen if before?” Park continued living with the Pak family, but gradually Moon’s 13 other children began to figure out that he was their half brother. Not all of them took it well; Park says that the eldest of Moon’s sons, Steve, once pointed a gun at him and threatened to rape and kill his mother. (Steve, who had a taste for cocaine and high-caliber weapons, was famously prone to violence. He would die of a heart attack in 2008, at the age of 45.)

But Moon’s second oldest son, Heung Jin, who was about Park’s age, embraced him as family. During his high school years, Park regularly visited Heung Jin at the Moons’ estate in New York’s Hudson Valley, where the pair spent their days hiking and talking about girls (a forbidden subject). Park, who longed for acceptance by the Moon family, recalls this as the happiest period of his youth.

In the winter of 1984, Heung Jin, who was then 17, smashed his car into a jack-knifed semi on an icy New York road and died. Park was so crushed he could barely pry himself out of bed—even today, he breaks down crying when the topic arises. “It was probably the most devastating thing that ever happened to me,” he says.

Shortly before Heung Jin’s death, Park had moved in with his mother. Most of Moon’s followers still believed that Park was the Paks’ son. To avoid raising questions, Park and Choi kept largely to themselves. “I let very few people close to me,” Park says. “There were ramifications for a lot of people if I didn’t maintain that identity. It shaped how I related to others in that I became guarded and private.” Initially, Bo Hi Pak continued playing the father role; he bought Sam a car and paid much of his tuition at George Washington University, where Park earned a bachelor’s degree in history. Park, meanwhile, clung to the hope that Moon would one day acknowledge his existence. “I remember Sam saying, ‘I just want him to recognize me publicly as his son once before he dies,'” recalls one member of the Pak family, who confirmed many details of Park’s account.

In a bid to win his father’s love, Park married the daughter of a church elder at a Moon-officiated mass wedding in Seoul in 1992. The couple celebrated with a lavish reception at a South Korean hotel, complete with ice sculptures and floral mosaics—all underwritten by the Pak family.

After the wedding, Park’s wife moved in with him and his mother in Virginia, where he was a partner in a small money management firm. But Park says she and her parents, who knew Park’s family secrets, treated Choi coldly, which created friction in their marriage. According to Park, his wife eventually admitted that Mrs. Moon had approached her before the wedding and asked her to spy on him and his mother—an allegation his then-wife denies. (The Unification Church and lawyers for Mrs. Moon declined to comment.)

Park says his marital woes destroyed what was left of his faith. “Suddenly, the blinders came off,” he recalls. “I could see how strange life inside the movement was—the things we did, the way we thought. When you begin to break free from that kind of brainwashing, it’s almost like an out-of-body experience.” Eventually, Park’s marriage crumbled. In 1999, he and his wife divorced (a taboo in Unificationist circles). Afterward, he left his firm and moved with his mother to Arizona. Park began period of soul searching. “He was looking for a father figure,” says Donna Orme-Collins, a former church member and close friend of Park’s. “He would get overly excited by different schools of thought that would help him find peace.”

By this time, changes were afoot in Moon’s movement. With the collapse of global communism in the late 1980s, Moon’s focus shifted increasingly to promoting family values. He launched the American Family Coalition, which quickly became one of the nation’s leading religious conservative organizations. And he worked with religious conservative leaders and the lobbying group Christian Voice on a grassroots campaign to nudge the Republican Party toward social conservatism. These efforts, and his political largess, earned him plaudits in high places. Speaking on the Senate floor in July 1993, Sen. Trent Lott (R-Miss.) urged fellow lawmakers to celebrate True Parents Day—a holiday honoring the Moons—in the name of family values. “It is in the interest of society and government to adopt policies strengthening and sustaining fathers and mothers,” he said. The following year, Congress passed a bill designating Parents Day a national holiday.

While lawmakers were lauding Moon’s family values message, his own family was unraveling. In 1998, his ex-daughter-in-law, Nansook Hong, published a devastating expose of Moon family life, which claimed that her husband, Steve, blew huge sums of church money on cocaine and beat her during her pregnancy. Hong and Moon’s estranged daughter, Un Jin, went on 60 Minutes, where they presented a litany of allegations about drugs, sex, and corruption inside Moon’s church. They also disclosed that Moon had an illegitimate son named “Sammy.”

These revelations struck at the heart of Moon’s teachings, and his followers began drifting away. Had Park and Choi gone public at this point, it could have worsened the fallout. Once again, Moon’s loyal deputy Bo Hi Pak took steps to protect his leader. In late 1999, he approached Choi and Park with a contract releasing Pak and the Moons from “any and all past, present or future actions,” and relinquishing all inheritance claims. The contract also stipulated that the agreement’s terms and any “personal differences” would remain confidential, meaning Park and Choi could never speak of their relationship to Moon. In return, Park and his mother would each receive $100.

Park and Choi ultimately signed the deal. They maintain they did so because Moon’s then-personal secretary, Peter Kim, promised that Moon-owned entities would pay them $1.5 million, plus $20 million if Park wasn’t tapped for a leadership role in the family’s business empire upon Moon’s retirement. (Through a church representative, Kim declined to comment.) According to court records, over the next several months, Park and Choi each received two lump sum payments totaling $1.5 million from an offshore account with ties to Moon-owned entities.

Up until this point, Choi says Moon had paid her roughly $35,000 a year through the Washington Times—even though she never worked for the paper. (Moon had a history of dubious financial dealings: A 1978 congressional investigation found his organizations “systematically violated US tax, immigration, banking,” and currency laws. He also served 18 months in a US prison for tax evasion.) But after the deal was signed she and her son were cut off from the Moon and Pak families. Gradually, they ate through the $1.5 million. Park says they lost about a third of it in the stock market. The rest they spent or gave away. Those who know Park say he was generous, especially to former Moon disciples, many of whom gave everything to the church and wound up destitute. In one case, Park helped to pay for a Unificationist missionary and his family to vacation at Disneyland after his 11-year-old daughter was diagnosed with leukemia.

Around 2006, Moon, who was in his 80s, began dividing his business empire up among his children. Two years later, he named his youngest son, Sean, as his spiritual successor. When it became clear that Park would not be tapped for a leadership position, he and his mother began pressing Bo Hi Pak for the additional $20 million they were allegedly promised. Pak moved to have the dispute heard by an arbitrator, based on an arbitration clause in the contract. Park and Choi couldn’t afford the arbitration fees, so a friend introduced them to Robert Hirsch. A slight man with scraggly bleached-blond hair and skull-shaped rings studding his fingers, Hirsch was once a high-rolling Manhattan lawyer. But in 1994 he and his partner, Harvey Weinig, were convicted of laundering millions of dollars for Colombian drug cartels, in a scheme involving rabbis, diplomats, and a police officer. (Weinig, who was also found guilty of aiding a kidnapping and extortion scheme, later had his sentence commuted by then-President Bill Clinton.)

Despite Hirsch’s tainted past, Park says he and his mother came to trust him and asked him to handle the arbitration. But Hirsch, who had lost his license to practice law, was barred from arguing the case. So the three of them hashed out an agreement: Hirsch would pay all legal expenses, and Park and Choi would sign over the rights to any award or settlement to him, with the verbal understanding that they’d split the money. Hirsch, who now goes by Reuven Ben-Zvi, maintained that this arrangement would allow him to become a party to the case and represent them in the proceedings because litigants in civil cases can represent themselves. But the deal put Park and Choi at the mercy of a convicted felon.

Ultimately, Hirsch and the lawyer he enlisted to assist them, Alisa Lachow-Thurston, failed to file key paperwork or show up to the July 2010 arbitration hearing. Lachlow-Thurston says she was just a “side assistant” and made no decisions about “what to file when and how.” Hirsch maintains they chose not to participate after discovering that the arbitrator assigned to the case worked for a law firm that had business ties to the firm representing Bo Hi Pak. “Sam and Annie could continue in the biased arbitration—without me—or they could elect to not further participate in the arbitral proceedings,” he says. If they had taken part, Hirsch argues, they would have forfeited their legal rights to “pursue redress in the courts.”

Bo Hi Pak traveled from his home in South Korea for the hearing. According to sealed transcripts, which were obtained by Mother Jones, he admitted under oath that he was not Park’s father, even though his name is listed on Park’s birth certificate. He also claimed to have no idea who Park’s father was and said he’d raised him as a favor to Choi. “I was fond of her at that time,” he said, “and really want[ed] to help her somehow.”

The arbitrator ultimately found the release agreement was valid and rejected Park and Choi’s $20 million claim. A county court affirmed the ruling. Alleging Choi and Park had been victims of “theology-based” racketeering, Hirsch appealed in 2011, but the district court refused to hear the case.

The legal battle has taken a heavy emotional toll on both of them, and their financial situation has grown increasingly shaky. Their Phoenix home is on the brink of foreclosure, and Park is inching toward bankruptcy. Whatever the outcome, they are ready to finally leave their painful double lives behind. By going public they also hope they can help other Moon disciples break free from the Unification Church. “So many people sacrificed for the movement, but they didn’t really know what they were sacrificing for,” Choi says, weeping. “I used to worry about my financial future and about my son’s security. But now it’s very clear to me: My job is to light the candle—to light a candle so that people can see that the entire movement was built on a lie.”