Children stand amidst the rubble of Cebu, Philippines, after Typhoon Haiyan. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/69583224@N05/10844671344/sizes/c/in/photolist-hwiLY9-hwiM6d-hwiMk1-hwiLSY-hvMWzo-hvMBY5-hvLPJc-hwWaKR-hwX3tc-hudgy1-hueD5c-hudgPw-hudgBY-hvZXW9-hvhWZw-hvixCC-hvjj64-hwhcJq-hwhcyq-hwijwa-hwhctL-hwhcJW-hwijoK-hwhctf-hwijvZ-hwhcK7-hAa3bC-hsoc6T-hD1BmX-hut5nR-hynZVy-hD1XPm-hD38DB-hD1ChK-hD3jM8-hD1F1v-hD3iuD-huzhMv-hpRBJB-hwXooL-hpRVi5-hpT56k-hurCVy-hv5eFG-hv4DJ5-hxk8Ey-hv4pJF-hv4DF9-hv62kr-hxfSL1-hvLD8w/">EU Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection</a>/Flickr

Aid agencies are still digging through rubble in the Philippines in the wake of Super Typhoon Haiyan, which was just one of many record-smashing oceanic storms to spring up in the last decade. Insurance adjusters have already pegged Haiyan’s price tag alone—counting damage to homes, businesses, and farms—at $14.5 billion. Today, as politicians and policy wonks dive into a second week of UN climate talks in Warsaw, the Philippines’ lead delegate has called for developed nations whose industrial emissions drive climate change to foot the bill for disasters like this. It could be one hell of a bill: Natural disasters altogether have cost the world $3.8 trillion since 1980, according to a new report from the World Bank.

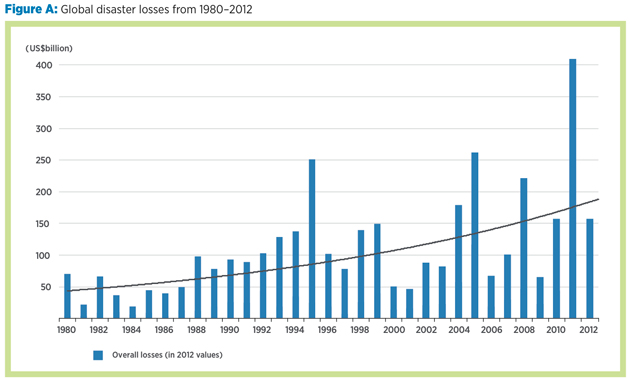

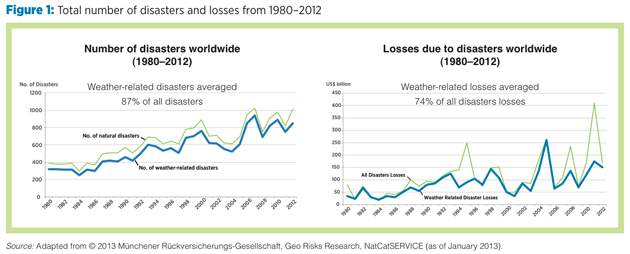

Using data from Munich Re, the world’s largest reinsurance (insurance for insurers) agency, World Bank analysts found that 74 percent of that cost arose from weather-related disasters like hurricanes and droughts. They also found, as the chart below shows, that annual costs are on the rise, from around $50 billion a year in the 1980s to $200 billion a year today, thanks to a rising number of disasters and growing economic development:

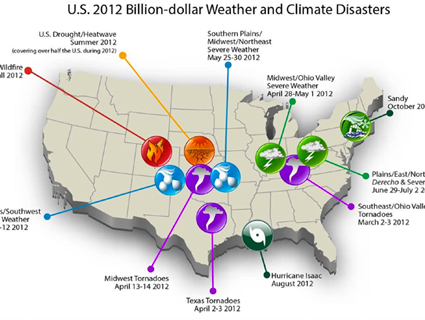

In the United States, last year was the second-most expensive year on record for weather disasters, with Hurricane Sandy and drought in the Midwest pushing the total to more than $100 billion. And another recent World Bank analysis found that without significant investments in protective infrastructure, flood damage alone could cost coastal cities worldwide $1 trillion every year by 2050. While not every event can be linked directly to climate change, predictions for increased sea level rise and extreme rainfall in the tropics made in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report suggest these costs aren’t likely to recede anytime soon.

“We’re not able to stop storms,” World Bank Vice President for Sustainable Development Rachel Kyte said from Warsaw. “That puts a lot of infrastructure at risk, as well as a lot of lives and livelihoods.”

Not just the cost, but the total number of natural disasters is on the rise, up roughly 183 percent since 1980, according to the study:

The task for negotiators in Warsaw, Kyte said, is to hammer out an international arrangement to help developing nations—which are disproportionately impacted by extreme weather—find the cash to rebuild after future disasters like Haiyan. One option is to hold big polluters like the United States and European Union financially liable for climate impacts, beyond their contributions to relief efforts; EU delegate Juergen Lefevere dismissed this approach as an impossible “blame game” in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, given the difficulty of assigning responsibility for individual events to climate change.

Kyte said that while she sympathizes with the “narrative around equity and justice” driving calls for climate reparations, the ultimate solution will likely entail rich countries diverting some of the money they would normally pay into humanitarian aid funds and development banks into a new program that poorer nations could tap after disasters to rebuild in a stronger, smarter way that accounts for future climate change. Developing countries, she said, “need to be able to access additional resources to pay for the additional cost of building back better.”