Photograph: Greg Ruffing

Anticipation is rising on a night in early August as about 300 starry-eyed libertarians gather at George Mason University in Arlington, Virginia, for a lesson on how to save the Republican Party, the Constitution, and maybe America. The hero they’ve come to see is Justin Amash, a 33-year-old Michigan congressman who has spent the previous two months crusading against National Security Agency surveillance. The GOP gadfly is joined by three other congressional newcomers who serve as Amash’s ideological sidekicks. As the crowd jumps to its feet to greet Amash, one young activist can’t contain himself: “I’m on a first-name basis with the man who wants to save the Fourth Amendment!”

Just one week earlier, Amash had brought the House of Representatives to a standstill with a measure that would have prohibited the NSA from indiscriminately collecting Americans’ phone and internet data. Leaders in both parties opposed his amendment, but Amash had sensed an opportunity to capitalize on strong bipartisan disgust over the surveillance scandal. In just a few days he’d cobbled together 205 votes split almost evenly between Republicans and Democrats—and might even have seen his measure pass had House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and the White House not applied last-minute pressure to stop it.

Amash and his colleagues are greeted as liberators at the Young Americans for Liberty Convention, one of the dozens of initiatives spawned by the 2008 presidential campaign of Texas Rep. Ron Paul. Every so often the crowd of twentysomethings breaks into chants of “End the Fed,” or into a chorus of boos at the mention of establishment figures like Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham, whose existence Rep. Mick Mulvaney of South Carolina invokes the way a Hogwarts first-year might hint at Lord Voldemort.

The event has the feel of a fraternity reunion. At one point, Mulvaney takes an “End the Fed” trucker hat from an audience member and places it atop the curls of his colleague Thomas Massie, a Tesla-driving mechanical engineer who last year came out of nowhere to win one of Kentucky’s congressional seats. Rep. Raúl Labrador of Idaho finishes the night with a winding joke about Amash’s support for legalizing prostitution. And like any good brotherhood, they even have an initiation ritual: As the forum ends, Amash walks over to Mulvaney to recognize him formally with a custom red-and-gold “liberty pin” reserved for his closest allies in the House. A voice cuts through the din as they exit the stage: “We love you, Justin!”

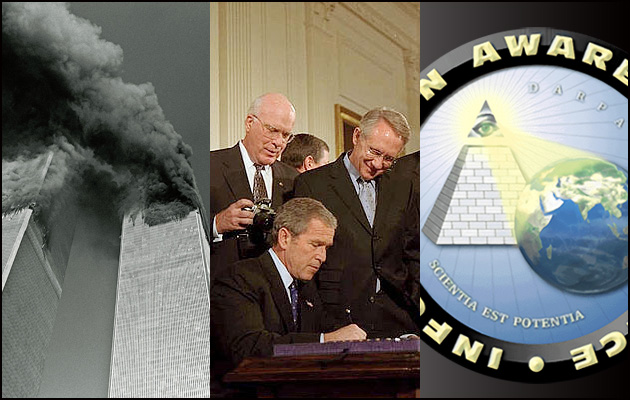

After a decade of aggressive expansion of the national security state, Amash, a Star Trek-tweeting, Justin Bieber-quoting amateur arborist from Grand Rapids, has emerged as an unlikely leader of the most serious rebellion against unchecked surveillance powers since 9/11. He’s also become a driving force in the fight for the future of the libertarian movement long led by the retired Paul—and perhaps even for the soul of the deeply fractured GOP.

His tactics have defied Beltway conventions. “There are committee chairmen that fear Justin Amash,” says Rep. Jared Polis, a liberal Colorado Democrat who has worked closely with him on surveillance issues. “That is rare for a second-term member.” Michelle Richardson, a legislative counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union, calls Amash “a game-changer.”

Washington can’t quite get a read on Amash. Karl Rove calls him a “liberal Republican“; Democrats insist his fiscal policy makes Paul Ryan look like a New Dealer; some in the GOP establishment just straight up say he’s an asshole. But after his campaign against the NSA, what no one can do is ignore him. Not only has Amash flouted the respect-your-elders path for making it in Washington, he’s also built a case that libertarianism can amount to more than just a protest vote. Increasingly, when he denounces government spending, military intervention, and abuse of executive power, Amash has company from both sides of the aisle.

Amash believes he’s at the vanguard of a generational shift in how Congress approaches a whole range of political issues. The word he likes to use is “realignment.” At the forum in Arlington, when asked to explain what sets the four horsemen on stage apart from the old guard, Amash breaks into a huge smile. “Everything.”

The most immediate thing that stands out about Amash is that, for someone who never misses a vote and uses Facebook to report on each one he takes (some 2,000 and counting), he spends an inordinate amount of time trolling people on the internet. (Amash himself uses that term, telling the activists in Arlington that “I’m on those forums; I’m trolling the forums.”) Favorite targets include McCain, whom he views as pretty much everything that’s wrong with Washington (McCain, for his part, calls Amash a “wacko bird“), and Canadian pop star Justin Bieber (who has not weighed in on Amash). This is, in part, simply the way millennials communicate. But it also reflects two defining elements of Amash’s political rise—his distaste for DC decorum and his aversion to compromising on core issues.

Problem with Republicans is we think we’re selling good pizza. We could learn a lot from @dominos.

— Justin Amash (@justinamash) January 17, 2013

The son of immigrants, Amash was not politically active until his mid-20s. His Palestinian father lived in a refugee camp in the West Bank until 1956, when a church offered to sponsor his family’s emigration to the Midwest. Attalah Amash arrived with $17 in his pocket but thrived in western Michigan, where he married his wife, Mimi, a Syrian immigrant, and launched a successful hardware business. Justin, the middle of three brothers, attended the University of Michigan and then stuck around Ann Arbor to earn a law degree.

Although he largely avoids discussing his heritage now, back in 2006 it compelled him to write a letter to USA Today protesting negative coverage of the Iraq War. Contrary to his anti-interventionist rhetoric these days, Amash aligned himself with the neoconservative proponents of the war, hammering the claim that Arabs might not be naturally disposed to democracy as “not only historically mind-boggling but also patently offensive.” He now calls Iraq a mistake “in retrospect” and says of his earlier views, “I was pretty young at the time.”

It was not long afterward that Amash discovered libertarianism and its irascible chieftain, Ron Paul. As he tells it, one day he stumbled upon the Wikipedia page of F.A. Hayek, the Austrian economist lionized by Paulistas. He breezed through Road to Serfdom, Hayek’s hatcheting of the nanny state, and found his calling.

In 2008, Amash—who by then worked as a corporate lawyer and helped manage the family’s tool business—poured $73,000 of his own money into a state House race to win a seat in Lansing, where he quickly went about distancing himself from basically all of his colleagues. “We would joke, ‘Oh my gosh, Amash is voting no again!'” recalls Barb Byrum, a former Democratic state legislator. (At least 70 times Amash was the only one to cast a no vote.) “I know some media outlets are fawning over his supposed bipartisanship, but it doesn’t square with the state rep I served alongside of.”

Even some of his fellow Republicans were peeved, but Amash’s work caught the eye of the conservative grassroots; after a year at the state capitol, he had about 10,000 fans following the explanations he posted for each of his votes on Facebook. He connected with his role model, Paul, through the congressman’s brother David, a local pastor, and flew to Texas to meet him. With the support of big-time conservative players like the Club for Growth and Grand Rapids-based Amway magnates Dick and Betsy DeVos (Amash went to the same high school as their eldest son), Amash powered his way through a crowded primary in 2010 to replace a retiring GOP congressman in Michigan’s 3rd District.

In Washington, Amash’s propensity for pushing “nay” won him the admiration of Paul and ingratiated him with a handful of young colleagues also ushered in as part of the GOP’s 2010 tea party wave. (Politico named him “most likely to lead a rebellion of the nerds.”) He voted “present” on a bill to defund NPR on the basis that the measure was probably unconstitutional, and he launched a quixotic effort against commemorative coins, which he considered to be a form of backdoor earmark.

His habit of bucking party leaders was not without consequences. After he voted against Paul Ryan’s budget plan last year, the House Republican Steering Committee stripped him of his committee assignments and his seniority, ostensibly for his lack of party discipline. What really set off the leadership, though, was something else—what Lynn Westmoreland, a veteran Republican congressman from Georgia, termed “the asshole factor.” Amash didn’t just break with his colleagues, he trolled them. On Facebook, he explained to his growing cadre of followers that Ryan’s plan wouldn’t have actually produced a balanced budget until 2040.

Why should one man control the value of money? What does God need with a starship? Equally perplexing questions. #EndTheFed #StarTrekV

— Justin Amash (@repjustinamash) June 7, 2012

Amash viewed the committee purge as a betrayal by a party that “doesn’t tolerate dissent or independent thinking.” He told the National Review that John Boehner would be smart to avoid western Michigan for a while, and when it came time to elect a new speaker in January, Amash cast his vote for his friend Raúl Labrador instead.

“The Republican leadership put him in a position where he’s got nothing to lose,” says Marcy Wheeler, a Grand Rapids-based blogger who regularly writes about civil liberties and national security at Emptywheel. “He doesn’t need their funding. He doesn’t owe them anything.”

When I asked him about the reprimand after a town hall in his district, Amash brushed off the question. “I didn’t have to rethink my role” to make an impact, he said. “I lost my committee spot because I was making an impact.” Or, as he put it on Twitter: “Some Members of Congress are playing checkers. Others are playing chess. I’m playing Star Trek 3D chess.”

What that also meant was pushing his own balanced-budget amendment in lieu of Ryan’s, and in an unusual fashion: He asked all 434 of his colleagues if he could come to their offices to try to sell it, in presentations running as long as 30 minutes. More than 100 accepted, even if the legislation seemed dead on arrival. It was a curiosity; as one Democrat confessed, it was the first time in his three decades on the Hill that someone from the opposing party had invited himself in like that. Amash was able to enlist 14 Democratic cosponsors, even though his plan dramatically slashed the social safety net. His door-to-door pitch highlighted his ambition to be more than just DC’s next “Dr. No.” One of Congress’ most uncompromising radicals was also in the coalition-building business.

Amash began his second term with the aim of reining in the surveillance state. Spurred by the Justice Department’s seizure of Associated Press phone records, he introduced legislation to stop the executive branch from collecting data from telecom companies without a warrant. Amash had been building a base of support with monthly meetings of his Liberty Caucus. As the gatherings shifted from fiscal issues to civil liberties, they were sometimes joined by Democrats.

When ex-intelligence-contractor Edward Snowden began exposing the NSA’s massive surveillance programs through leaks to the Guardian and the Washington Post last June, Amash shifted into high gear. He teamed up with Rep. John Conyers, a liberal Michigan Democrat and a longtime skeptic of government power, to restrict the NSA’s operations. Amash’s amendment would have narrowed the scope of data collection to only individuals under investigation. (In a separate measure, Amash also sought to make the classified opinions of the FISA court that oversees NSA requests available to all members of Congress, not just those on the House Intelligence Committee.)

As Conyers and Polis worked their Democratic colleagues, Amash and his staff put together a spreadsheet of GOP members they’d have a chance of swaying; he spent the next couple of days personally lobbying more than three dozen of his conservative colleagues, including Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.), who had written the statute being used to justify the NSA’s activities and was stunned at what it had become.

Amash worked both the procedural and theatrical sides of the battle: While his aides wrangled with House staff to craft language that couldn’t be tossed out on a technicality, he used social media to threaten an ugly intraparty fight. By the time he finally cornered Boehner on the House floor to make his case for a vote, he’d cobbled together a large enough cohort—as many as 250 backers by his own whip count—that Boehner risked an open insurrection if he buried the measure. When Boehner caved, the White House intervened against it—the first time in eight years, Amash says, that an administration had weighed in on an amendment to a House bill. Civil liberties advocates hailed the effort as a breakthrough. “One of the major upshots of the Justin Amash story is that standing by principles can work politically,” says Jim Harper, the director of information policy studies at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. Conservatives traditionally do not object to broad government surveillance, Harper points out—but Amash had forced the issue.

Amash viewed the roll call vote as evidence of a sea change. “If you were a Republican who was in Congress for five years or less, you were likely to support my amendment, actually,” he says. “We won the majority of those Republicans. If you were here for more than five years, you were overwhelmingly likely to vote against my amendment.”

He had learned a lesson from the December purge, but not the one Boehner had in mind: Trolling can work. “The mainstream Republican group in Congress would tell you that the way to make an impression nationally is going along with the mainstream, getting your committee assignments and so forth, and maybe in 10 or 12 years you might have some input,” says Mulvaney. “Justin has turned that entire system on its ear.”

If Amash represents a new twist on the DC libertarian, it may be despite, not because of, his connections to the movement’s best-known leader; part of what makes him a compelling figure is the extent to which he breaks from his mentor. “He’s more thoughtful and less curmudgeonly than Ron Paul,” says Polis. “Ron Paul also clung to a lot of outdated social sentiments.” Adds Mulvaney, a cosponsor of the NSA amendment, “Dr. Paul was easily dismissed by sort of the mainstream Republican party in Washington because to a certain extent he was”—he catches himself—”he did come across as a little bit crazy. Justin’s been able to deliver much the same message in a much more marketable package.”

Amash has been aided by a demographic shift in Congress and in the party’s grassroots, as self-described “liberty” Republicans have increasingly moved into positions of influence, riding a tide of anti-Obama obstructionism. Consider Preston Bates: In 2012, the 23-year-old college dropout from Louisville, along with his friend John Ramsey, a wealthy undergrad Bates met on the Paul campaign, launched the super-PAC Liberty for All with the goal of electing more Paulistas. Their first project: pouring $650,000 into a Republican primary in Kentucky to help Massie beat the GOP establishment’s candidate. A bitcoin promoter who refers to his curly mop of hair as “the Rand-fro” (like that of Paul’s son Rand, the Kentucky senator), Massie quickly established himself as Amash’s co-conspirator and best friend in Congress. (Amash calls him a “godsend.”)

“Justin Amash was the kind of person who persuaded me that I was libertarian-inclined,” Bates says. He rattles off a list of some of his favorite Amash moments, like the time the congressman trolled White House press secretary Jay Carney on Twitter, and then he collects himself. “I kind of feel like a boy describing a school crush.” Liberty for All propped up another Paul-inspired candidate, Kerry Bentivolio, a reindeer farmer seeking an open congressional seat outside Detroit. The PAC boosted the spending of the first-time candidate and Santa impersonator by a factor of 10 to help him win the primary, and Amash helped mobilize voters in the general election. (Bentivolio’s accomplishments in Washington so far include referring to American Samoa as “American Somalia” on the House floor and calling for Obama’s impeachment over unspecified constitutional violations.)

GOP leadership doesn’t like that I explain votes @ http://t.co/4dJV5pGi. I’m “egregious a**hole” for shining light on waste.

— Justin Amash (@repjustinamash) December 13, 2012

When it comes to influencing policy debate, Amash may yet eclipse Paul the Younger, who scored points with some trolling of his own on the issue of drones but has been hampered by the same kind of conspiratorial whispering and racist associations that tarnished his father’s career. Rand’s first campaign spokesman was a KKK-sympathizing singer in a satanic metal band; one of his Senate aides held an annual party to drink to John Wilkes Booth. Then there was his stated disapproval of the Civil Rights Act, and his incessant fretting about the president’s nonexistent plans for national gun confiscation. Amash has taken what civil libertarians of all stripes appreciated about Paul’s father, while largely leaving behind the baggage.

“With Rand Paul sometimes it’s a clown show—his stuff isn’t serious,” observes Wheeler. “I think Amash increasingly has the press pull of the Pauls, but he’s actually working more closely with the civil liberties community in DC, and I think they trust him to be able to work on these issues.”

Yet there are limits to Amash’s brand of post-partisanship. That’s because he doesn’t just want the government out of your data: He wants it out of practically everything else too—public education, central banking, industrial investment, and the Middle East. (Amash, the only member of Congress of Syrian heritage, loudly warned that any military action against Bashar al-Assad would be unconstitutional without congressional authorization. He also showed up at a classified briefing on Syria wearing a Darth Vader shirt.) On the fiscal front, he thinks the Ryan budget doesn’t go far enough: “He’s for sequestration on steroids,” says Garrett Arwa, executive director of the Michigan Democratic Party.

One notable exception to Amash’s leave-me-alone ethos: He believes fetuses are protected by the 14th Amendment and supports banning all abortions. And while Amash was an outspoken critic of the Defense of Marriage Act, arguing that such issues should be left up to the states, as a member of the Greek Orthodox Church he’s personally opposed to same-sex marriage. When I ask him in Arlington if he’d support a lawsuit from a lesbian couple challenging Michigan’s prohibition on gay marriage, he hesitates. “I don’t know enough about the particular case,” he says. “But my position has stood since the beginning of time: I don’t think government should be defining marriage.”

I do not support the #hocuspocus plan that doesn’t really defund #Obamacare.

— Justin Amash (@repjustinamash) September 10, 2013

Ultimately, the fine points of his positions may not matter to the grassroots, which clearly sees him fitting right in with his libertarian forebears. Recently on CafePress, a “Paul-Amash 2016” trucker hat was going for 13 bucks.

I caught up with Amash in the middle of August at a community center in the farm town of Lowell, southeast of Grand Rapids. The town hall meeting was packed, the audience considerably older than the one he met in Virginia. This was a district whose dairy and corn farmers rely on the crop subsidies Amash has pledged to eliminate, and where voters have long favored more moderate Republicans—including their onetime 12-term congressman, Gerald Ford. Yet Amash was greeted enthusiastically.

The area has “enough of a Democratic presence that I don’t think any Republican representing it until now has thought that he should stray too far from what is considered mainstream Republicanism,” says Bill Ballenger, a former GOP state senator who runs the website Inside Michigan Politics. “But with Amash, it’s ‘Katie, bar the door.’ He doesn’t give a damn.”

Amash’s team started off with a dig at the NSA and never really strayed from that course. “Put your phone on silent, turn it off—there’s an NSA joke in there somewhere,” his district adviser warned the crowd. Then, after a plug for his Facebook page, Amash launched into a brief lecture on why voters should care about Edward Snowden as much as he did.

“I’ve looked at private lawsuits myself,” he said when asked if citizens have any recourse against Fourth Amendment violations. And he couldn’t resist getting in a few digs at his party’s leadership. “Republicans give cover to the White House on many of these issues.”

His constituents were thoroughly spooked. “It sounds like Russia, doesn’t it? Communist Russia,” said one attendee.

“It’s very scary,” Amash said.

“Is it too late, Justin?” asked another.

“I don’t think it’s too late.”

Afterward, Amash made a quick exit, but a handful of folks stuck around, still buzzing about the NSA. “Justin’s tops,” said a constituent from nearby Ionia. There was just one problem. “He’s still too young to be president.”