<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rig_wind_river.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>

What if a gas company wanted to set up a fracking rig on your property? What if you found out that you couldn’t say no? A new report from Reuters explains how tens of thousands of homeowners across America suddenly found themselves vulnerable to this nightmare scenario, as they discovered that their deeds cover their surface land but not the rights to the minerals beneath it. And as the American energy boom opens new land to extraction, homeowners from Florida to California to Washington to North Carolina have discovered that they unknowingly signed away the rights to what’s under their property. And they might not be able to do anything about it.

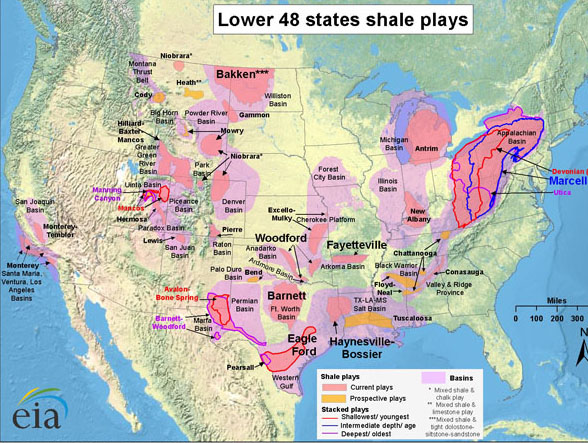

Mineral rights—the right to extract and profit from whatever is under the ground—are more and more commonly being separated from land deeds, and in many cases, sellers aren’t legally required to disclose that the estates have been split. After reviewing property records in 25 states, Reuters found that D.R. Horton, the biggest home-builder in the US, “has separated the mineral rights from tens of thousands of homes in states where shale plays are either well under way or possible, including North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, Oklahoma, Utah, Idaho, Texas, Colorado, Washington, and California.” When the rights are split from the property deed, homeowners not only have no say, they also don’t see royalties from the drilling, which paid out more than $20 billion nationally in 2012.

The impacts can go way beyond potentially having a well pad show up on your doorstep. According to Reuters:

Loss of mineral rights isn’t the only hit homeowners take. Property-tax assessments don’t take into account severed mineral rights. And “lenders may not be willing to extend mortgage loans on property that is subject to intensive gas extraction activities,” according to a report last year by the North Carolina Department of Justice.

Wells Fargo, the nation’s largest home lender, sometimes denies mortgages to homes encumbered by gas leases. And for the past year, Sovereign Bank has been including clauses in mortgages allowing it to declare borrowers in default if any part of the subsurface property has been “leased, assigned or otherwise transferred for use to extract minerals, oil or gas,” according to a copy of the bank’s mortgage addendum. If mineral rights are severed, “we would not move forward with financing a property,” said a bank spokeswoman.

Insurance policies usually exclude damage from “industrial operations,” and some companies are denying coverage altogether for homes where the mineral rights have been severed. Title insurance companies have been exempting anything to do with mineral rights from their policies, too.

Landowners have pushed back with mixed results. The D.R. Horton returned mineral rights to a group of 700 angry homeowners in North Carolina after an inquiry by the state Department of Justice. But some individuals haven’t been so lucky. Earlier this year, Martin Whiteman of West Virginia lost an appeal for an injunction and damages after Chesapeake Appalachia—a subsidiary of Chesapeake Energy—used ten acres of his 101 acre sheep farm to set up three wells and a series of disposal pits that rendered the land practically unusable. As the practice expands and more people discover that a few lines of legalese have radically changed the deal they thought they were getting, it’s possible states will clarify how developers have to disclose this practice. Until then, it’s buyer beware.

The whole piece is worth a read. You can find it here.