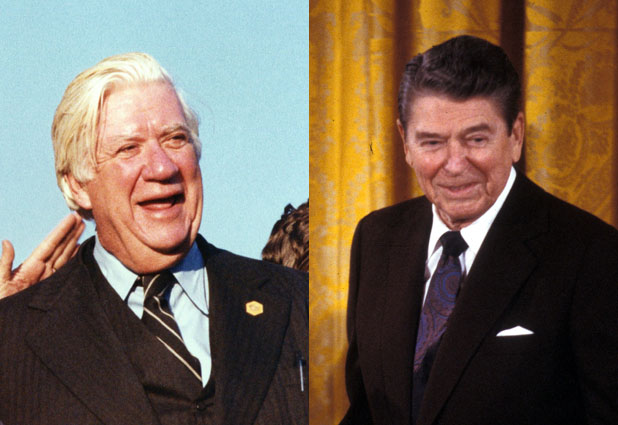

O'Neill: Carter Archives/ZUMA; Reagan: Arthur Grace/ZUMA

My pal Chris Matthews has a well-timed book coming out next week. A quasi-memoir, Tip and the Gipper: When Politics Worked chronicles the odd-couple relationship that conservative icon Ronald Reagan and liberal workhorse Tip O’Neill developed after Reagan became president in 1981 and had to contend with the Democrat-controlled House that O’Neill presided over as speaker. Matthews was present at the creation of this pairing, serving as a young aide and strategist for the experienced, feisty, and crusty O’Neill. In fact, Matthews, as he explains in this gripping, behind-the-scenes, first-person account, was recruited as an O’Neill lieutenant by other Democrats seeking to bolster O’Neill’s national standing and touch up his media skills so the speaker could have a chance in the coming political warfare between him and the popular and telegenic 40th president of the United States.

The subtitle is something of a spoiler, giving away the moral of this story. It also proclaims the here-and-now relevance of this engaging patch of history, for yes, children, once upon a time partisan arch-rivals in Washington were able to fight fiercely over profoundly important policy matters, hurling tough words and concocting clever ploys to gain the upper hand, without threatening government shutdowns or financial crises, without hostage-taking, and without resorting to the most excessive rancor. More significant, amid these bare-knuckled battles, these two strong-willed political foes were able to put aside acrimony to craft the occasional compromise, such as an accord to raise taxes (to tame deficits), legislation to strengthen Social Security, and a jobs bill to counter the ravages of recession. Government was divided, but it sort of worked.

Matthews’ take on Reagan may be more charitable than some liberal Hardball devotees would prefer. (Here’s my summation of the Reagan years.) But Matthews is telling a political tale, and though he was a front-row participant in the story, he admirably adopts an evenhanded approach (not shying away from pointing out O’Neill’s missteps) to serve up his big point: Political combat is necessary and important for the nation, but it need not be self-destructive and nuclear. And one of the first Tip-Gipper deals demonstrates this—and shows how far off the track today’s GOPers have strayed.

It was a month after Reagan’s inauguration, and once more Congress faced the task of raising the debt ceiling so the nation could pay the bills the House and the Senate had already accrued. In a few weeks’ time, the current Congress will be handed the same unpleasant job, and tea party GOPers are now threatening again to block an increase in the debt ceiling—a move that could trigger a financial crisis at home and abroad—unless President Barack Obama assents to dramatic spending cuts or the defunding of Obamacare.

In early 1981, Reagan, who successfully campaigned against President Jimmy Carter as a champion of slashing government spending, had to ask Congress to boost the debt ceiling. The previous year, as Matthews notes, not a single GOP House member had supported increasing the borrowing limit when Carter needed to do so. Yet with the House then in the hands of the Democrats, it didn’t matter. Carter had the votes. The measure passed. But that vote gave Republicans political ammo; they could attack the Dems for creating more government debt (even if that was not accurate).

When his turn came, Reagan faced a different situation. He couldn’t raise the debt ceiling and avoid a government default without the help of O’Neill and the opposition party. The speaker was not as brash—or irresponsible—to seize hostages in these circumstance. But he did desire a deal. Matthews writes:

When Reagan’s top [congressional] lobbyist asked [O’Neill] for his support in getting the debt ceiling raised, the Massachusetts Democrat made a simple request. He wanted Max Friedersdorf to relay back to his boss precisely what the deal would be, which was that he, Tip O’Neill, wanted a personal note from the president to each and every Democratic member of the House asking for his or her support in the matter of raising the debt ceiling. Friedersdorf agreed on the spot and carried the message back to Reagan. The asked-for letters arrived the next day—all 243 of them.

It was a small, telling episode. Here was the Democratic congressional leader proposing a wholly pragmatic cease-fire. The debt ceiling vote had offered each side a chance to discredit the other. O’Neil proposed avoiding harm to either party.

O’Neill could have caused a crisis and disrupted Reagan’s first weeks as president by instructing his House Democrats to vote “nay.” But he opted not for obstructionism:

The sole condition he’d made stemmed from his desire to help protect the sitting members from their opponents’ likely attacks come the next election. To accomplish this, he needed Ronald Reagan’s cooperation. Looking to the future, if a Republican challenger were to slam one of O’Neill’s Democrats for big spending, pointing to his vote to raise the debt ceiling as evidence, the note from Reagan would give him adequate cover. As an effective solution, it was an arrangement that worked, for both sides—and the republic moved on.

Moving on—that seems to be what tea party Republicans want to prevent these days. But back in the time of Tip and the Gipper, the GOP’s goal was to shrink government, not blow it up. And Reagan and his crew—sometimes to the annoyance of Reagan’s die-hard ideological allies—realized that compromise and deal-cutting were not mortal sins; they were part of governance. (Reagan, by the way, raised the debt ceiling 18 times during his two terms as president.)

Many a commentator in recent years has huffed that these days Ronnie would be branded an accommodationist and driven out of the GOP. Perhaps. But I imagine he’d find his spot. A fellow who could conjure up false facts and anecdotes at the drop of an index card to support conservative orthodoxy would not be out of place in the modern Republican Party. Yet at a time when the nation keeps reliving GOP acts of political terrorism, Matthews is providing a public service by recounting an era when even the most ardent partisan gladiators could bend toward pragmatism, if only to keep the republic moving and allow for other battles to ensue. And if Matthews had three decades ago told O’Neill and Reagan that they were overseeing what would come to be seen as the glory days of bipartisanship in Washington, this pair of tough Irish American pols would have probably asked the young fella what he was drinking.