Zhang Naijie/ZUMA

As I think of Syria today, two neighborhoods of Damascus are on my mind.

One is Yarmouk, a neighborhood of mostly Palestinian refugees and their descendants. When I think of the “the camp,” as it was so often called, I don’t usually think of the fact that its population has shrunk to a fraction of the 112,000 people that once lived in that 0.8 square-mile space. I don’t think about allegations of a little-reported chemical attack there last July. I don’t think about the shelling and crushing of homes.

When I think of Yarmouk, I think of that hour, at about 4 a.m., when pious old men shuffled to the mosque to begin the day and clutches of young people walked home with a swagger to end their night. I think of the way the sky at the end of Palestine street would turn pink at the end of the afternoon as I carried bags of cucumbers or peas or cherries home from the market. I loved how the streets felt lived in—how they filled every night with scraps of fruit rinds and newspapers and plastic bags yet were clean by the morning. I loved that everyone lived so close together in Yarmouk and that the voices of gossiping women and kids playing soccer in the alley blended with the music of Fairuz and Um Kalthoum and the cooing of pigeons in our windows.

When I think of Yarmouk, I think of Mazen’s house. Mazen had done five years as a political prisoner, but he didn’t really talk about it much. He was the glue to an intellectual and cultural circle in the camp. Most Thursday nights, he’d cook an elaborate feast and sometimes he’d show a film or people would read poetry or someone would present their photography. Later in the night, the music would come on. Some would dance, flicking their wrists above their heads and jutting their hips sideways. Others would spill out onto the little courtyard, where conversations would build: Was Obama better than Bush for the Middle East? What was the best collection of Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry? Was it wise to ally with “enlightened sheikhs” to spread political messages through the mosques? What was the future of Assad?

When I left Yarmouk in July 2009 for a short trip to Iraqi Kurdistan, I had no idea it would be the last time I’d see it. One friend, Ayman, saw us out that morning. He was quite a bit younger than me, but he was always worrying about us. “Be careful,” he said as we left. I couldn’t have imagined that in a few days, my girlfriend (now wife) Sarah, my friend Josh, and I would be captured and thrown in Iran’s Evin prison. Or that within a few years government snipers would position themselves on Yarmouk street and pick off men who entered the camp.

Ayman (not his real name) had agreed to take care of our plants while we were away. A handful of days after we left, he saw a report on our capture on the news. He went back to our apartment and sat there alone, silently. Then, he gathered up as many of our things as he could—our trinkets from Yemen and the Old City of Damascus, my Arabic books, the beautiful short stories of the Syrian writer, Zakaria Tamer. (I love his shortest of all: “A sparrow left his cage, and when he grew hungry, he returned to it.”) He took all these things and stored them in his parents’ house. He left Sarah’s dry-erase board just as it was.

Our friends went to the Iranian Embassy to plead our case, taking considerable risk in identifying themselves with Americans whom Tehran was accusing of espionage. A few days later, the secret police took over our apartment. Ayman never went back. Neither did we.

Before living in Yarmouk, we lived in the far north of the city. The neighborhood was called Muhajireen, and it clung to the side of Mount Qasioun. Had it been in the United States, Muhajireen would have been prime real estate, perched so high above the city. In Damascus however, the rich didn’t like to climb hills. Most people didn’t, really. It was difficult to get our friends to come there, it felt like such a trek.

It was a hard climb, it’s true. I remember walking down on winter days, sliding on ice as I descended. Cars would skid and slip sloppily down the hill. I’d walk down to the bottom of the hill, past the cemetery where people dusted off their loved ones’ tombstones, past the mosque that held the tomb of ibn Arabi, the 13th-century Sufi philosopher. I’d enter suq al jumaa, the most beautiful market I’ve ever seen, where barrels of brightly colored pickles were stacked along the cobbled roads. The air smelled of spice and fresh bread.

Muhajireen was like an incredible little secret—you could see almost the entire city, all 1.7 million people of it, from up there. At dusk, I’d sometimes go up onto our roof. I’d watch pigeons take flight from the coop on our neighbor’s rooftop, spiraling upward in tight circles so high that they almost became invisible. Then, with a piercing whistle and a wave of a bright flag, my neighbor would send them diving back toward the earth, swooping straight into their coop. I could see such flocks of pigeons rising across the entire city, tracing little rings in the sky.

We often sat on the roof at night too, smoking apple tobacco from our argilla pipe and reading the roads of the city, laid out in front of us like a giant illuminated map. As I stared at the Old City, a vaguely circular 5,000-year-old patch in the midst of straight lines, I’d often think of the prophet Muhammed. Legend has it that he stood atop Mount Qasioun as he passed through Syria. From its apex, he looked down on the city of Damascus, but declined to enter it. “Man should only enter paradise once,” he said.

Even after we moved across the city to Yarmouk, I would come back sometimes to go up on Mount Qasioun and look out over the city at night. The last time I went up there, Sarah, some friends, and I climbed up just above the line of houses. We wanted to go farther, but we stopped short when we saw what looked to be a military base.

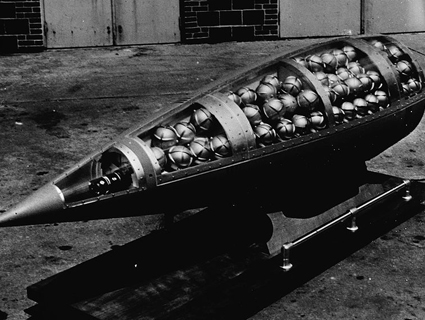

I couldn’t have imagined rockets flying down from that spot and waking people before dawn, making them choke and kick and scream, shrinking their pupils down to needlepoints. I don’t know for certain that chemical weapons were launched from there, as some have reported—the United States is now saying some were shot from another base. What I do know now is that the base we came upon when we climbed that night was a station of the Republican Guard and that it is one of several sites that witnesses said they saw rockets raining down on Ghouta the night of the chemical attack.

If the United States does decide to strike in Syria this station will almost certainly be a target. If there are chemical weapons there, will they explode? Which direction will the wind be blowing—away from, or toward the houses beneath the pigeon coops?

Sometimes, when I think of Damascus, I think of a park on the edge of Yarmouk. It was barren—some plastic chairs and tables placed across an expanse of mostly dirt. Neon lights hung off dry, leafless trees. Nearby, a grumpy man was perpetually chasing children out of his artichoke field. I’d often go there in the afternoon. In the distance, Assad’s presidential palace seemed to be looking over us, over everything.

“You see this road?” a friend asked me one day as we sat there, pointing to the street that hugged the edge of the camp. “This didn’t used to be here. When I was a kid, if you came out past these houses, this was all fields. Then Assad built this road all the way around the camp so they could gain access to it quickly, should they need to.”

Not long after the uprising began, Syrian rebels occupied the camp and the military put it under siege. Most of our friends left, but Ayman’s family stayed. Eventually, the Syrian military burned their house down.

Still, they didn’t go. One day, Ayman’s family drove down Yarmouk Street, that thoroughfare I remember as a teeming stretch of glitzy shops, internet cafés, and juice bars. As they drove, a bullet from a sniper pierced the front window and entered Ayman’s stepdad’s head. He died instantly alongside his wife and stepdaughter.

I had met him once, at Ayman’s house. We were eating pizza. I remember the night being warm. He came home to find Ayman dancing in the middle of the living room for no apparent reason. I think the music on the stereo was Algerian, which was the rage at the time. He hugged his wife and gave her a kiss, then he sat down on the couch, laughing and watching as Ayman continued to dance.