The Obama administration is nearing the end of negotiations on one of the most far-reaching international free trade agreements in US history. The deal, called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), is aimed at boosting trade among 12 participating countries, and the next and final round runs from July 15 to 24. The negotiations don’t just concern the selling of shoes and toothpaste across borders; the trade deal, which will be the product of a three-year process, has the potential to affect many areas of American life. And because information on the negotiations is not public, it’s hard to know what those impacts will be. Here’s what we do know so far:

What countries are involved? The TPP currently includes the United States, Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. But it could eventually include half the countries in the world.

$0 to $650 (in billions)

?

How will it affect US law? The agreement, which has a total of 26 chapters, could affect a host of policy areas, ranging from intellectual property rights to product safety and environmental regulations. Here’s how: To make trade easier between countries with different sets of regulations, parties to international trade pacts have to bring their regulations into accordance with common international standards. This can lead to pressure to revise rules in areas like the environment and food and workplace safety in the United States, according to trade experts Josh Meltzer, professor of international studies at Georgetown Law School, and Susan Aaronsen, professor of international affairs at George Washington University. Once the agreement becomes international law, countries can also sue the United States for what they see as violations of the agreement, which can compel Washington to alter US law and regulations.

What’s with the secrecy? The American public is not allowed to see the text of this deal while its being negotiated. This has some lawmakers and advocacy groups up in arms. Several members of Congress have recently called on the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to release the draft that is under construction to the public, but to no avail. The text will become public once the final deal is signed by all countries.

Trade deals always operate under a certain level of secrecy, trade experts say, which makes it easier for countries to negotiate amongst themselves without too much noise from advocacy groups and others inside countries. “That is how trade deals have worked…if they are made public, all interested groups can start tearing things apart before it’s even done,” says Bryan Riley, a senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation. But there is precedent for releasing proposed trade deal information to the public. A full draft text of the Free Trade Area of the Americas was released in 2001 during negotiations on that 34-nation pact; a draft text of the recently-completed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement was released; and the World Trade Organization posts negotiating texts on its website.

So who does get to see it? Members of Congress and a trade advisory council—which includes groups from industry and civil society—consult with the USTR and get to see the TPP negotiating texts. But many members of Congress are not happy with their level of access.

Two congressional committees—the House ways and means committee and the Senate finance committee—have jurisdiction over trade, and are in close communication with the USTR about the deal. Staff of members on the key committees are allowed to see proposed negotiating texts, but for other congressional staffers it’s not so simple. A spokeswoman for the USTR says the agency “works closely with staff of other committees that have jurisdiction on issues potentially affected by TPP, including providing access to review US proposals.” But a staffer for a senator on the finance committee, as well as two staffers for members who are not on the committees, told Mother Jones they have not yet been granted access to the negotiating text.

The same staffers say that their offices have experienced major delays in obtaining sections of proposed TPP text they requested from the USTR. (One did receive the requested text; the other two have not yet.)

Reps. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) and Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) have also asked the USTR to observe negotiations, but they have not received permission to do so. In the past, Congressional delegations have been allowed to observe negotiations during important trade deals.

“The administration has not yet provided a level of transparency in the TPP talks that would more fully enable Congress…to offer their valuable input,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), who is chair of the senate finance subcommittee on trade, wrote in an email to Mother Jones. Lawmakers have been concerned about transparency in previous trade deals, but there is extra concern regarding the TPP because of the number of sectors of the economy it could affect, lawmakers say.

The trade advisory committee does get to see proposed negotiating text. It is made up of some 700 members, and according to the USTR “was created to ensure that US trade policy and trade negotiating objectives adequately reflect US public and private sector interests.” The advisory council includes a few dozen members from labor, environmental, and consumer groups, but it is heavily dominated by corporations and industry trade groups. (The USTR maintains it also consults with civil society groups outside of the advisory committee.)

What’s in the deal? Because negotiations are not finished—there is still one more round to go—no one knows exactly what will be in the final agreement. With the working texts not public, it’s even harder to know which way negotiators are leaning. “One downside [of secrecy] is its critics can assume the worst-case scenario, and proponents can assume best-case scenario,” Heritage’s Riley says. Here are some of the worries that lawmakers and advocacy groups have about the deal:

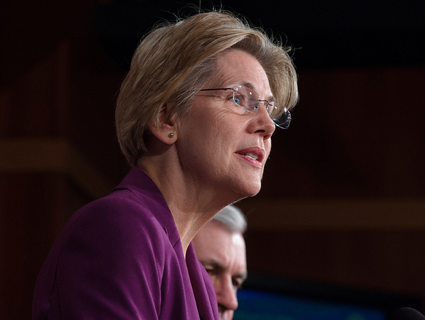

- Financial regulations: As Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) warned at a Senate Banking Committee hearing in May, “There are growing murmurs about Wall Street’s efforts to use the Trans-Pacific Partnership…as [a] vehicle…to water down the Dodd-Frank Act. In other words, trying to do quietly through trade agreements what they can’t get done in public view with the lights on and people watching.” The financial industry has indeed been pressing the USTR to use the deal to roll back financial reform. The Coalition of Service Industries, a trade association whose members include Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, and American International Group, recently wrote a letter to the USTR urging TPP negotiators to soften rules on US financial firms operating abroad. A spokeswoman for the USTR says that as of yet, the TPP does not address these regulations.

- Intellectual property provisions: According to a version of the intellectual property chapter of the TPP leaked over a year ago, participating nations would be held to much stricter copyright laws than now exist under current law. The draft says that member nations would have to make criminal penalties available for copyright infringement “on a commercial scale,” which could include something as small as downloading a single copyrighted song. After the leak, the USTR announced the deal would include “exceptions and limitations” to these copyright provisions “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.”

- Food, workplace, and environmental rules: The TPP has the potential to alter a variety of US regulations governing everything from food quality to labor standards to environmental rules. DeLauro is concerned with food safety in particular, “because of the likely influx of possibly contaminated food into the United States,” she says. The USTR insists it is aiming for the deal to raise standards, not lower them. But Aaronsen says the trade deal could easily push regulations in the United States in the opposite direction. “TPP could be a good thing,” she says, but because of the lack of transparency, “We don’t know.”

- Jobs provisions: The TPP revives the decades-old debate over whether trade deals create or kill jobs. In November, 23 mostly Democratic senators, including Wyden, Sherrod Brown, Al Franken, Barbara Boxer, and Kirsten Gillibrand, wrote a letter to the Obama administration expressing their concerns that the TPP could weaken the already fragile employment situation in this country: “Trade when done right should create and preserve good American jobs instead of outsourcing them,” they wrote, and urged that the TPP not restrict “Buy American” and “Buy Local” government procurement policies. “These trade agreements are often good for large corporations and not so good for American workers,” Brown told Congressional Quarterly in March. The USTR responded, “For every $1 billion in American goods and services that we export to other countries, we know that about 5,500 jobs are supported right here at home.”

What’s next? The TPP is due to be signed between countries in October, but the talks may drag on until spring. And it is unclear whether members of Congress will ever be able to see the entire contents of the massive trade deal before it’s finalized. Right now, the Obama administration is operating as if it had something called fast-track authority. Under fast-track, which expired in 2007, Congress permits the president to negotiate and enter into a trade agreement without Congress amending the deal or voting on it beforehand. After the trade pact is finalized, Congress does have to vote to implement it, but trade experts say it is unlikely that Congress would vote down the product of a complex, three-year, multiparty negotiating process that the GOP largely supports.

Despite the range of issues at stake, the massive Trans-Pacific Partnership hasn’t received much attention. “In general, people don’t care about trade,” Aaronsen says. “I’m saying, ‘Guys, this is where it’s at’…We’re talking about things that have a huge impact on the social compact.”

Front page image by EDHAR/Shutterstock.