A surprising percentage of the public thinks Arctic warming is reverberating here at home.Armin Rose/<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&search_tracking_id=V5XuBqB-8p9uxqiZaydgkg&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=arctic+climate+change&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=6749344&src=mMzqC0uVQuTjAjhkh3WXYw-1-21">Shutterstock</a>

From Superstorm Sandy to wildfires, droughts, and freakout temperatures, weather extremes have been hitting the United States hard. And simultaneously, a new scientific theory has emerged to explain much of this weather weirdness: Climate change is warming the Arctic more than the mid-latitudes, leading to a loopy jet stream and, in turn, all manner of weather extremes, including both heat waves and also excessive cold.

What’s striking is that even as scientists continue to debate this idea, the public seems to buy into it. Or at least, that’s the upshot of a new study in the International Journal of Climatology, reporting on a series of surveys of residents of the state of New Hampshire (whom, the paper notes, are pretty representative of Americans as a whole when it comes to their views on climate change). From Fall 2012 through Spring 2013, 1,500 Granite Staters were asked the following question: “If the Arctic region becomes warmer in the future, do you think that will have major effects, minor effects or no effects on the weather where you live?”

Here’s the stunning result: 60 percent of respondents answered “major effects,” and another 29 percent answered “minor effects”—leaving just 11 percent saying “no effects” or professing that they did not know. Overall, then, 89 percent of these New Hampshire respondents thought changes in the Arctic would reverberate far beyond that region, and would affect their weather in the mid-latitudes. “Research on an Arctic/weather connection is new, but it seems to be reaching the public,” says Lawrence Hamilton, co-author of the study and a sociologist at the University of New Hampshire.

The study contained two additional noteworthy findings. First, in a reprisal of the notorious “smart idiot” effect, Democrats and Republicans polarized over the issue of the Arctic’s influence on weather, and that polarization got worse with increasing levels of education. Thus, highly educated New Hampshire Republicans—GOPers with postgraduate degrees—were the least likely political group to accept the idea of an Arctic influence on their weather. Democrats with postgraduate degrees were just the opposite—they were the most likely to accept it.

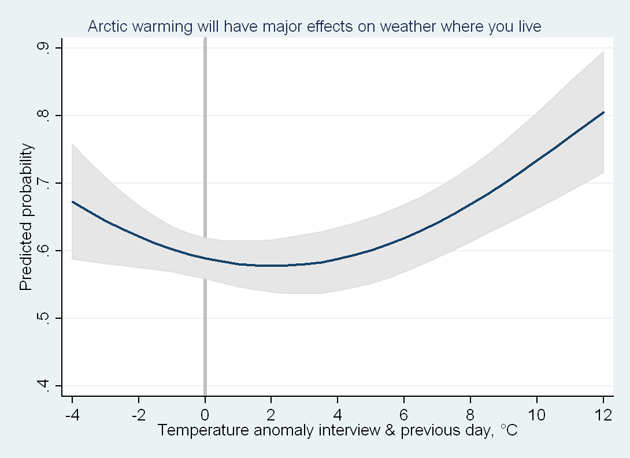

Perhaps still more interesting, belief in an Arctic influence on the weather depended on…the weather. In the study, the researchers compared respondents’ answers with the temperature on the day in which they were surveyed, and the temperature on the preceding day. They found that belief in an Arctic-weather connection increased with both abnormal heat and also abnormal cold:

One upshot of the research? That President Obama’s new climate communication strategy—focused on talking about the weather, rather than talking about “green jobs”—gains some more empirical support in its favor. “Our results indicate some degree of public acceptance for scientists’ global perspective in which Arctic change has consequences far outside the Arctic, and for studies showing that changing probabilities of extreme weather events are a key aspect of climate change,” says Hamilton.

In other words: It’s the weather, stupid. People get it—and so, it seems, do politicians.