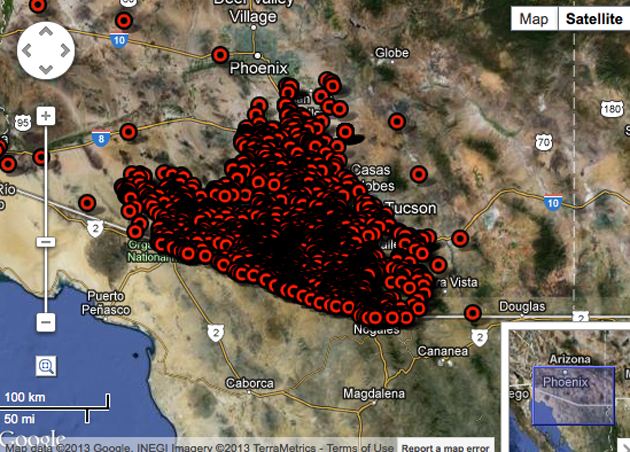

Every documented migrant death in Pima County, Arizona, from 2001 to 2013Courtesy of Humane Borders

Pima County, Arizona, has found a new tool in the quest to save lives along the US-Mexico border: data. On Monday, the county medical examiner’s office and Humane Borders, a human rights group based in Tucson, unveiled the Arizona OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants, an online mapping tool that allows anyone to search the hundreds of known deaths of migrants in the county since 2001.

The app, based on information compiled by the medical examiner and other sources and made possible by an anonymous $175,000 grant to the county, could help identify the unclaimed bodies of migrants and reunite them with their families. The data can be sorted by gender, cause of death, approximate location, and the victim’s last name, if known. The medical examiners “get these calls from people—’My loved one disappeared three months ago, five months ago, at this point,'” says John Chamblee, a researcher at the University of Georgia who helped create the app. “Or they’ll get a call like, ‘The smuggler called me,’ and they left their loved one at this point and they try to find out about them.” Now can just create a custom map using whatever information they have, and sift through the results.

The Pima County data’s impact is potentially far-reaching. Humane Borders hopes better tracking will help reduce the number of fatalities across the borderlands by giving aid workers an idea of where to place food and water. The data can also be used to trace shifts in migrant traffic and how policing strategies affect migrant safety. In Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, the number of migrant deaths jumped from 52 in 2011 to 129 last year, an alarming increase immigration experts attributed to more effective strategies to block crossings in Arizona. Researchers like Princeton University sociologist Douglas Massey have attributed the swelling number of deaths along to the militarization of the border: With easily followed geographic corridors closed off, migrants are forced to travel through less navigable terrain, where they may become lost or run out of supplies. According to the Border Patrol, there were 463 migrant deaths in the Southwest in 2012, the highest total since 2005.

But Pima County is mostly alone in its quest for better information on migrant deaths. Only a handful of other counties, such as Imperial in southeastern California, have even produced reliable data. Data collected by the Border Patrol is unreliable, and not very specific. (One of Chamblee’s challenges was to reconcile often contradictory data sets maintained by the border patrol, foreign consulates, and the Pima County medical examiner.) As Mother Jones has reported before, the Pima County medical examiner is unique because it is wholly independent of law enforcement, which means it faces less political pressure and fewer distractions. In some smaller counties in Texas, for instance, coroner is just a part-time job.

It’s not that officials in other counties don’t care about the issue; they’re just worried that the data would be misused. “Some of them think politically don’t think it’s a good idea to create this,” said Kat Rodriguez, a program director at Coalición Derechos Humanos Arizona. “Suddenly the narrative would be, ‘Oh my God, look how much money is being spent on these illegals.'”

The Pima County project looks at a slice of a larger dataset that does not exist for now. Draft legislation floated by the White House in February included language requiring US Customs and Border Protection to collect statistics on deaths along the border. It would be required to publish those statistics at least once a quarter and issue a report within one year of the bill’s passage analyzing any trends and recommending actions to prevent such deaths. The draft immigration bill being considered in the Senate has no such provision, nor do any proposed amendments. In the meantime, Pima County’s program will have to do.