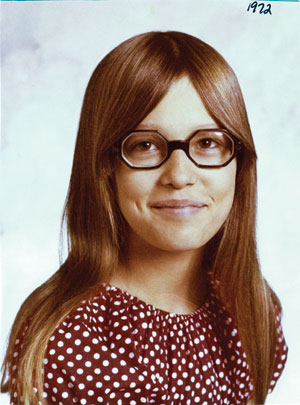

Mark with Houston at Houston's high school graduation in 2009Courtesy of the family

For more on this story, read Mac McClelland’s new chapter at the New York Times Magazine. It was also featured on the New York Times’ podcast, The Daily, which you can listen to below.

THE THING THAT STRUCK ME when I first met my cousin Houston was his size. He wasn’t much taller than me, if at all, and was slight of frame. On the other side of the visitors’ glass, he looked surprisingly small, young for his 22 years. The much more remarkable thing about him turned out to be his vocabulary, vast and lovely, lyrical almost—until it came to an agitated or distracted halt. In any case, all things considered, he seemed altogether extremely unlike a person who had recently murdered someone.

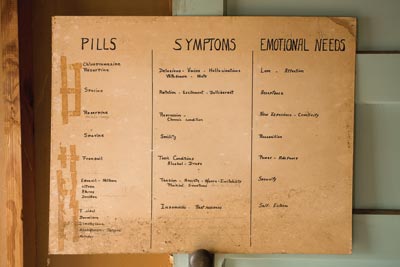

The symptoms displayed by Houston (in my family, a cousin of any degree is simply “a cousin”; technically, Houston is my third) in the year preceding this swift and horrific tragedy have since been classified as “a classic onset of schizophrenia.” At the time, it was just an alarming mystery. Houston had been attending Santa Rosa Junior College, living with his mom, playing guitar with his dad, when he became withdrawn and depressed. He slept all day; his band had broken up, and suddenly he had no friends. His dad, Mark, who had once struggled with depression and substance abuse but was now a pillar of the recovery community, and his mom, Marilyn, tried to help, took him to a psychiatrist. Houston didn’t have a drinking problem, but he mostly stopped drinking anyway. He didn’t smoke pot anymore, or even cigarettes. His psychiatrist indicated possible schizoaffective disorder in his notes, but put Houston on a changing regimen of antidepressants over the next eight months. It didn’t make any difference. Houston had started stealing his mom’s Adderall. He said it helped him feel better. He got fired from multiple jobs. Marilyn kicked him out, and he moved in with Mark.

“This was not my nephew,” my Aunt Annette, Mark’s sister, says of Houston’s behavior then. “He was always solicitous and loving and talkative with me. Now, he was anxious, quiet, said very strange things. He would say things that seemed not to come from him. I asked him how his therapy was going, and he said, ‘Terrible.'”

Toward the end of Houston’s devolution, he started having violent outbursts, breaking furniture; he tossed his mom across a room. Desperate now, Mark and Marilyn called the psychiatrist repeatedly and asked what to do. He told them to call the police.

“You can call the police,” the deputy director of Sonoma County’s National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), David France, said when I asked him what options are available to a parent whose adult child appears to be having a mental breakdown. “The police can activate resources,” like an emergency psych bed in a regular hospital, or transport and admission to a psychiatric hospital in a county that, unlike Sonoma, has one. But only if the police decide your child is a danger to himself or others can they arrest him with the right to hold him for three days—what in California is called a 5150, after the relevant section of state law. Otherwise you can be turned away for lack of space even if your loved one is willing to be admitted, or be left no good options if they’re not. Ninety-two percent of the patients in California’s state psych hospitals got there via the criminal-justice system.

But Mark didn’t want to call the police. For one, he didn’t think Houston was dangerous, just upset, despairing. Also, Mark read the news. The Santa Rosa cops had killed two mentally ill men they’d been called to intervene with in the last six years, one case resulting in a federal civil rights suit. This is not a problem unique to Santa Rosa—or to greater Sonoma County, which in 2009 paid a $1.75 million settlement to the family of a mentally ill 16-year-old whom sheriff’s deputies shot eight times. There’s no comprehensive data yet, but mental illness appears to be a factor in so many arrest-related deaths that the Justice Department has considered adding mental-health status to its national database of such deaths. Just last year, for example, the DOJ found the Portland, Oregon, police department had a “pattern or practice of using excessive force…against people with mental illness,” including eight shootings in 18 months and the beating to death of an unarmed man in 2006.

Anyway, Mark didn’t think three days of lockdown in a mental facility would make his son less unstable. He was looking for a meaningful treatment plan, not to rustle Houston through emergency services. “All those kids get shot by the police,” he told Marilyn. “Just let me handle it.”

So Mark didn’t call the police, and Houston didn’t get any additional help. Ten days before all the really bad things happened, Annette came out to visit from Ohio. “Honey,” she said to her nephew, “something’s going on with you, babe. Either something’s happened to you, or you’re not sharing something. I’m really, really worried that something’s going on.” She says he turned his head and looked at her eerily and said, “Maybe I’ll tell you about it sometime.” She says, “It didn’t even sound like him.”

He did tell her about it, later. He told her he’d been having delusions, something about telepathic communications and aliens and wireless circuits. Something about his mom and dad—who’d been divorced for a long time—and teenage sister, Savannah, being in an incestuous sex ring. Something about an invisible friend, Devon, and also that he’d been cutting himself to exorcise the evil, and that Mark was poisoning him with lead and was the source of the evil. He did tell Annette, but only after it was too late, after he came home from the gym late one November night in 2011 and stabbed his father 60 times, with four different knives. When Savannah came downstairs and called 911, it appeared he was trying to behead him.

“What the FUCK?” my Aunt Annette exclaimed around the one-year anniversary of her brother’s death. “HOUSTON, what the FUCK?” But, she told me, the fact that what Houston did was “so heinous” didn’t mean he wasn’t a victim, too. “There was no facility, no support. There was nowhere to take him; there was nothing to do but call the police.”

“There’s been no place to put my anger,” she said about losing Mark. “Because I love this child. I know how sick he is. I was there at his birth.” And then she asked me to do the talking for a while, because she couldn’t talk anymore because she was sobbing.

Psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey calls a crime like Houston’s “a predictable tragedy.” That’s what he has also called the Gabrielle Giffords shooting; he says the same thing about the Virginia Tech massacre, the Aurora movie theater shooting, the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting, and dozens of other recent homicides, some of them famous mass killings or subway platform shovings, but many of them less publicized. Ten percent of US homicides, he estimates based on an analysis of the relevant studies, are committed by the untreated severely mentally ill—like my schizophrenic cousin. And, he says: “I’m thinking that’s a conservative estimate.”

Saying that the severely mentally ill are disproportionately responsible for homicides has made Torrey, author of The Insanity Offense and the forthcoming American Psychosis, unpopular in some circles. “[My critics’] argument is you can’t talk about these things because it causes stigma,” he says. In the aftermath of the Newtown tragedy, some mental-illness advocates insisted that even if Adam Lanza had Asperger’s or any mental-health issues, it would be totally inappropriate to cite that as a factor in his actions. But other administrators and caretakers think it’s vital to bring up. “We have to think about mental-health care in a public health framework,” says Dee Roth, who is on the National Advisory Council of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). “Public health measures solved rickets, cholera, people dying when they’re 30.” But when it comes to mental illness, she says, “we’re not treating the sick people.” And while the details of Lanza’s diagnosis or any attempts to treat it remain unconfirmed, what is known, as Torrey pointed out in a piece he coauthored in the Wall Street Journal, is that Connecticut is “among the worst states to seek such treatment. It has among the weakest involuntary treatment laws and is one of only six states that doesn’t have a law permitting court-ordered ‘assisted outpatient treatment,'” which, Torrey notes, “has been shown to decrease re-hospitalizations, incarcerations and, most importantly, episodes of violence among severely mentally ill individuals.” Although even Torrey, who founded the Treatment Advocacy Center, an organization that pushes for fewer restrictions on involuntary commitment, admits that such measures would hardly plug all the holes in our mental-health-care system.

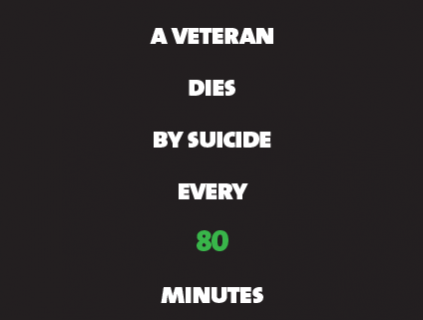

Obviously, lots of violence is perpetrated by the “sane.” And most violence committed by the severely mentally ill is committed against themselves. Even in the range of schizophrenia narratives, which commonly include suicide or dying on the street, Houston’s took an extraordinarily unhappy turn. But happy endings are getting harder for even the nonviolent mentally ill to come by. And as states and counties pare back what few mental-health services remain, we’re learning that whether people who need help can get it affects us all.

ON OCTOBER 12, 1773, the first patient was admitted to the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds in Williamsburg, Virginia, the first North American facility of its kind. The governor, an Enlightenment man, had prevailed upon the assembly to create a place where “a poor unhappy set of people who are deprived of their senses and wander about the countryside, terrifying the rest of their fellow creatures” could, with the help of experts, reclaim their “lost reason.” Over the next 100 years, the rest of the country followed suit, taking “lunaticks” out of cages in jail basements after Boston schoolteacher Dorothea Dix happened into one such dungeon in 1841 and launched a fact-finding and activism rampage that led to the establishment of 110 public psych hospitals by 1880.

About a hundred years after that, in 1977, my mother—Mark’s second cousin—dragged her 16-year-old baby sister kicking and ranting into Woodruff Psychiatric Hospital in Cleveland.

The day my Aunt Terri had a psychotic break, she just appeared in my mother’s backyard. The neighbor who was over babysitting my then-infant older sister didn’t know how long Terri had been out there when she finally noticed her, but she’d been pacing back and forth, long and hard and fast enough to wear a rut into the lawn. Raving in outer-space language. Flailing and swinging wildly.

“Do whatever you have to do to get her in the car,” the general practitioner said when my mom phoned him, after the babysitter called her home from work. The doctor had asked my mom to describe the scene. He’d asked my mom if she’d ever seen anyone act like that on any kind of drug. He’d told her to hold on and he’d call her right back after he contacted a special hospital in nearby Cleveland, and now he was telling her she had to get her sister there by any means necessary. So my mom told my Aunt Terri that she would take her to the airport, because the only discernible thing that Terri was babbling about was that Chris Squire, the bass player of Yes, was sending her messages that she needed to meet him in Canada right away.

It took five white coats to contain Terri as she tried to scream and fight her way out of the hospital lobby. The admitting doctor didn’t know—no one who saw her in the first months she was in and out of hospitals was able to decide—if Terri, straight-As bright and talented but a party girl, went crazy because she was doing drugs or if she was doing drugs to self-medicate symptoms of oncoming crazy. By the time I’d been born and grown old enough to understand what adults were talking about, it didn’t matter. Aunt Terri was schizophrenic. Period. When I was younger, I was afraid of her. Or on some level, I was afraid of being her, more likely, of not being able to tell the difference between real voices and voices in my head, of being pulled so deep into my imagination that I’d never get out. When I was a teenager, I gave her rides home from family gatherings, but only after hanging back and hoping someone else would offer first.

Last year, Aunt Terri died in her yard. My Aunt Paula came to pick her up for the weekly grocery shopping and found her dead in the cold winter grass. This isn’t as bad as it sounds, I tell people when that lands on their face as horror. It was, in fact, pretty much the best-case scenario. She died in her own yard, of her own home, where she lived her own life, young at 52, yeah, but not a terrible age for a body doused in antipsychotics and incessant cigarettes, giving out too early, but from the ever-desired “natural causes.” Yet more and more these days, Aunt Terri’s best-case scenario is an unlikely one. It took a lot of work, on the part of my grandma and Aunt Paula, and 23 years of dedication by a caseworker, work I didn’t even want to do for a 15-minute car ride, work nobody wants to do, work counties and states are increasingly not paying for.

THE HOSPITAL my mother checked Aunt Terri into no longer exists. Neither does the state hospital, CPI—Cleveland Psychiatric Institute—that she was taken to later. Had it not closed a few years after her break, she may have ended up living in it for the rest of her life. But the changes in Terri’s brain coincided with massive changes in mental-health policy.

In the 1950s, more than a half million people lived in US mental institutions—1 in 300 Americans. By the late ’70s, only 160,000 did, due to a concerted effort on the part of psychiatrists, philanthropists, and politicians to deinstitutionalize the mentally ill. Today there’s one psychiatric bed per 7,100 Americans. The motives behind this trend were varied, to say the least. Emptying the asylums was going to save money. Who needed asylums anymore, anyway, with all the great antipsychotics now on the market? Deinstitutionalization was going to restore citizens’ rights and protect them from deplorable conditions popularized by movies and memoirs and often all too real. “We were totally creeped out,” my mom remembers of walking into CPI to visit her sister. “It was exactly like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. People just sitting around talking to themselves and staring into space in hospital gowns”—a place where a sane person would go crazy and the crazy were unlikely to be cured. Wouldn’t it be better if the mentally ill were treated at home, given support and therapy and medication via a network of community clinics? Anyone who visited even a “good” mental hospital found that message appealing.

My grandparents tried bringing Terri home. They weren’t medical professionals, and for years she was in and out of the hospital as they struggled to get her to take her medication and to take care of her when she wasn’t stable. Once, when doing the dishes with Aunt Paula after dinner, she smashed a frying pan into Paula’s head, causing her to see stars and their brother to tackle Terri to the floor, the single act of aggression anyone ever saw him commit. Several months later, after she started a fight that ended with my grandmother’s arm broken, she was moved to a group home owned by a nonprofessional but sympathetic woman in Madison, Ohio, 20-some miles from my grandparents’ house.

The constant presence of other people continued to agitate Terri; within six months she was thrown out. Using Terri’s Social Security income and Section 8 housing assistance, my grandparents got her a duplex in Painesville. She was evicted. She got another apartment, and was evicted again. Two more group homes in Cleveland, evicted. She would go door to door, “bothering” tenants. She would lie on the sidewalk in her bathing suit. And she would always, always, always be blasting music. Another apartment, in Mentor: evicted. With CPI long since closed by now, and hospitalization no longer an option, Terri was running out of places to go.

When in 1961 a joint commission of the American Medical and American Psychiatric associations recommended integrating the mentally ill into society, their plan depended on the establishment of local facilities where mentally ill people would receive outpatient care. Congress passed a law providing funding for these “community mental health centers” in 1963, and states, already under pressure from the patients’ rights movement, downsized their mental hospitals faster than anyone had anticipated. Between Vietnam and an economic crisis and lack of political will, though, adequate funding for community services never came through. In 1980, Jimmy Carter signed the Mental Health Systems Act, aimed at filling the gap. But a year later Ronald Reagan, already known for eviscerating mental-health services as governor of California, took office and gutted it, then decreased federal mental-health spending 30 percent and shifted the burden to state and local governments. By 1985, the federal government covered just 11 percent of mental-health agency budgets. When the crucial community services that the mentally ill were supposed to receive as the hospitals closed failed to materialize, more and more of them ended up on the streets. By the mid-1980s, pretty much everyone in America agreed that deinstitutionalization was not going well.

“Homelessmentallyilldeinstitutionalized was one noun in the media at the time,” says SAMHSA’s Roth, who is the source of the oft-cited data point that a third of America’s homeless people are seriously mentally ill (helping to rebut the misconception then that they all were). In 1984, Dr. John A. Talbott, then president of the American Psychiatric Association, apologized for the association’s role in the disaster. “The psychiatrists involved in the policymaking at that time certainly oversold community treatment,” he said, “and our credibility today is probably damaged because of it.”

“Think of it as haircuts,” says Roth, who watched deinstitutionalization unfold in her 37 years as chief of evaluation and research at the Ohio Department of Mental Health. “In the age of the great gothic castle on the hill, mentally ill patients had everything taken care of. Health care, sleeping, eating, etc. When they got out, they were supposed to have everything. They got Medicare and Medicaid, but [policymakers] didn’t think about food. And haircuts. Clothes. How to find a place to live.” How to do laundry; how to grocery shop. How to ensure people who need meds take them. What to do with people who had too many behavioral problems to avoid being evicted six times in a row.

Fortunately for my aunt, she lived in a state that, as Roth explains, had some “very dedicated, very dogged” leaders at the Department of Mental Health who were determined to make Ohio a model for post-deinstitutionalization life. By the mid-’90s, my home state “was famous all over the country for all kinds of stuff,” she says. Independent-living initiatives. Supported-employment programs. Supported education. Home-based services for kids. Active and excellent case management.

It was an excellent case manager who ultimately helped solve my aunt’s housing crisis. Eleanor Dockry, a tiny woman with chin-length black hair and black-frame glasses, was assigned Terri’s case through Pathways (now called Beacon Health), a nonprofit outpatient service provider supported by the county Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services (ADAMHS) board—essentially the rump of what was supposed to have been the community-services network envisioned by the reformers of the ’60s—and a slew of other community organizations. Though I met her for the first time just a few months ago, she took care of my aunt for 23 years, a life jacket. Eleanor knew that you could only be evicted from so many places before no landlord in Ohio would rent to you, so she sat my grandparents down. “I think if you could afford to buy something for her, that would be good,” she said. My grandparents pulled the money together for a trailer in a mobile-home community near their house.

“I have my own place,” Terri bragged to my mother, beaming, at 36 years old. “Daddy bought it for me.”

Eleanor came by at least once and sometimes twice a week. She took Terri to her favorite restaurant, McDonald’s, or to the park, or to go buy her nieces Christmas presents with money she saved from her Social Security check. (Terri liked to give me bubbles and sidewalk chalk, even when I was in college.) Every three weeks, Eleanor took my aunt to get her antipsychotic haloperidol injections, which Terri stopped refusing after my grandfather convinced her they were necessary for her own and everyone else’s good. Eleanor took her to Neighboring, a local nonprofit, which offered field trips, skill-building lessons about cooking or doing laundry, and support groups about medication side effects, as well as art classes, the results of which were sometimes displayed in the local mall.

“She just had a few little problems” with neighbors once she was in her own place, Eleanor says. The rock music, of course. An obsession with hoses that made her turn them on and leave them on, flooding the driveway. “But since they owned it there’s nothing they could do.” She lived on her own for almost two decades. “She did better than you could really expect for someone so mentally ill.”

So mentally ill: According to the National Institute of Mental Health, the term “mentally ill” can be applied to a whopping quarter of the US adult population in any given year, because broadly, it includes everything from depression to attention deficit disorder. “Seriously mentally ill,” however, is used to describe severe functional impairments like major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, which occur in up to 6 percent of the population. Within the severely mentally ill schizophrenic population (about 2.4 million Americans), my aunt—who constantly talked to invisible people, and got “pregnant” at 19 with Yes bassist Chris Squire’s baby (“It always came back to Chris Squire,” my mom says), her belly swelling realistically huge with his imaginary baby inside it—classified as low-functioning, making her about as mentally ill as a person can be. Still. With family and a few resources in place, Social Security checks and housing subsidies and a great caseworker, “she was able to manage on her own,” Eleanor says.

At Aunt Terri’s funeral, my family asked that in lieu of flowers, donations be sent to the mental-health organizations that made her life possible. We nieces who lived out of town and couldn’t make it were instructed to honor Terri and her love of loud music by throwing ourselves a peace-disturbing one-person dance party at the time of the service, wherever we were. My grandma and Aunt Paula resolved to find a broke veteran (who turned out to be struggling with his own psychological issues) and to give Terri’s trailer to him. My grandmother wanted to help other people needing help since the government had helped Terri. “She was independent until the very end,” she says.

“I’m so grateful,” she says, “that we had so much support.”

“OHIO ONCE HAD one of the top mental health systems in the country,” lamented the National Alliance on Mental Illness in a 2011 report. “Today, after several years of significant budget cuts, thousands of youth and adults living with serious mental illness are unable to access care in the community and are ending up either on the streets or in far more expensive settings, such as hospitals and jails.”

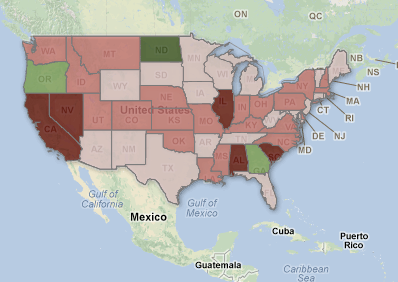

The glory days of Ohio’s mental-health department had already come to an end by the time the budget crises of the late 2000s rolled around. But the recession and the subsequent tea party austerity movement made things even worse. On the list of the 10 states that cut the most from mental-health budgets between 2009 and 2011, Ohio was No. 6. Then Gov. John Kasich’s 2012-13 budget slashed local government funds by a billion dollars and continued a trend of downsizing community mental-health programs. “The most fragile people in our society, we looked out for them,” the governor said. “And if there’s a hole or a mistake, we’ll come back later to figure it out.” (He’s since proposed restoring some services.)

“Ohio,” as Roth explains, “is a microcosm of the United States.” Collectively, states have cut $4.35 billion in public mental-health spending since 2009.

As in the rest of the country, Ohio allocates funds differently to different counties based on formulas and politics. My Aunt Terri was lucky to live in Lake County, Eleanor says. Not that it’s perfect there: All the Neighboring programs Terri once participated in have been eliminated, and the county doesn’t have the budget for enough group homes for its lowest-functioning mentally ill, which, if my family had been unwilling—or unable—to procure Terri her own place, would have been her last option. In this county of 236,000, there are a total of 18 “acute beds” in such facilities, so while Terri waited for someone occupying one of them to die, she’d have been checked into a psych ward at a hospital, and if Lake County didn’t have any psych ward beds open, she’d have been moved to a hospital in Summit County, an hour away, if it had a bed. Eleanor says the need for group homes contributes to homelessness in largely suburban Lake County, where the single operating shelter, 30 percent of whose residents are mentally ill, turns away 800 calls a year. But at least Lake County still had the funds to give Aunt Terri a caseworker.

In some other places, Eleanor says, people “just fall through the cracks.” Take next-door Cuyahoga County—home of the Cleveland Indians, and the largest mentally ill population in the state. William Denihan, CEO of the ADAMHS board there, explains that Cuyahoga has been the biggest loser, since the Ohio Department of Mental Health cut funding for community services there by 60 percent in 10 years. “The average county in Ohio got $4.20 per person” in state mental-health funding in fiscal 2012, he tells me in his office overlooking Lake Erie. But in Cuyahoga? They got 20 cents per person. Meanwhile, demand for beds in homeless shelters, along with emergency room and jail admissions, is exploding. “The prison population is the largest cost in Ohio,” Denihan shakes his head. “The largest mental-health hospital is our jail system.”

This is true across Ohio, where, 25 years into the Reagan-era policy changes but even before the recent austerity cuts, there were enough high-profile cases of mentally ill inmates being beaten, undertreated, killed by guards, or committing suicide to make it the subject of the 2005 Frontline documentary The New Asylums. But it is also true across the nation, where the three largest de facto psychiatric facilities are jails. In 2011, the sheriff of Cook County threatened to sue Illinois for making the jail the largest mental-health provider in the state. “We’re not set up to do that, obviously,” he said. As of 2006, 1.3 million of America’s mentally ill were housed right back where they were in Dorothea Dix’s day: in prisons and jails. Between 1998 and 2006, the number of mentally ill behind bars more than quadrupled; the share of mentally ill people among the incarcerated was five times higher than in the general population. More-recent national prison stats aren’t out yet, but in some county jails, mental-illness rates have increased by nearly 50 percent in the last seven years. It’s not uncommon for individual jails to report that 25 or 30 percent of their inmates are mentally ill, or that their mentally ill population rises year after year.

In Summit County, Ohio, just south of Cuyahoga, the sheriff announced last year that he would not “be a dumping ground anymore for these people,” and shut the jail to admissions of the mentally ill. He was the first sheriff in the country to do such a thing—somewhat ironic given that the county is exceptionally proactive in keeping the mentally ill out of jails. To make up for the lack of state funds, Summit County passed a dedicated mental-health levy on local property taxes in 2007. It is also one of five training sites in the nation for mental-health courts, which get offenders into treatment rather than locking them away.

“No one ends up in jail rotting,” Summit ADAMHS chief clinical officer Doug Smith promises me, dismissing the very notion of that happening here with a shake of his head. “We don’t have those problems here, like they have in California.”

Ah, California. No. 1 in the amount of mental-health funding cut from 2009 to 2011, No. 7 in cuts as a percentage. Home to one of the largest jail/psych facilities in the nation, the LA County Jail. Where visitors can’t believe how many bat-shit-crazy homeless we’ve got. Where deinstitutionalization was pioneered under Gov. Ronald Reagan with the 1967 Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which made it vastly more difficult to commit people, and where the rate of mentally ill in the criminal-justice system doubled just one year after it took effect. Where, often, the severely mentally ill live in jail for three to six months because they’re waiting for a bed to open up in a psychiatric facility. California: where, says Torrey, the psychiatrist who warns about “predictable” violence like my cousin’s, “they led the way in [deinstitutionalization], and they’ve led the way downhill. They’re certainly leading the way in consequences.”

THE TENDERLOIN, a neighborhood on the western edge of San Francisco’s downtown, has never been quite as infamous as New York City’s skid row once was, but it is no less deserving of its own depressing show tune. Emerging from the Civic Center subway station—with a guy stalking behind you barking, “Bitch. Bitch. Bitch”—you can generate a tour of movie-drama levels of abandoned humanity by simply doing a 360-degree spin. See a guy in a camo jacket selling four boxes of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese, cursing at unsellable mac and cheese. A guy rubbing his hands and smelling them, rubbing his hands, smelling them. A guy with a skateboard and chatty invisible friend to his lower right; another guy earnestly preparing a crack pipe; a filth-covered gal sitting and staring intently at nowhere; a lady with one shoe, no bra, a high ponytail, and a confused face, weeping and glancing around, lost in the broad light of day.

“This is not a ghetto,” says Cindy Gyori, executive director of Hyde Street Community Services, one of the city’s underfunded community mental-health centers. “Nobody is born here. They’re looking for the end of the rainbow,” and they end up here because San Francisco has “a reputation for being open.” Of the 1,000 individuals the clinic sees per year, 44 percent walk in the door homeless. Fifty percent admit to substance abuse. From wherever they came, “they bring their problems with them.”

Gyori, a petite white-haired lady with an exuberance you wouldn’t expect to last 20 minutes, much less 40 years, in this neighborhood—its 35 square blocks host 6,000 homeless people and 72 crimes on any given day—joined the civil and patients’ rights movement that had helped a cost-cutting Gov. Reagan pass Lanterman-Petris-Short. As a social worker, she experienced deinstitutionalization shake out; she’s had to call the police, invoking LPS’s Section 5150, on “lots of people” who “didn’t know how to take care of themselves” and were a threat to their own or others’ safety. But she still disagrees with those who think it should be easier to get people committed, medicated, or treated against their will. Whether they’re in their “right mind” or not, she says, mentally ill people should be able to do whatever they choose until they’re a danger—just like non-mentally-ill people. That violence has often already occurred by the time someone gets 5150’d is, Gyori says, a necessary “complication of our rights in America.”

What of the studies that show that involuntary-treatment laws decrease rates of violence and hospitalization and incarceration among severely mentally ill patients? Such laws are “stupid,” Gyori says. If your concern is public safety and crime prevention, she adds, “it’s the funding that matters.” Funding for school screening programs that could catch signs of severe mental illness. Funding for early treatment to keep the moderately mentally ill from becoming a lot sicker, and funding for rehab programs for those who didn’t get treatment and started self-medicating. Funding for intensive case management, subsidized housing for people who are functionally disabled. All things that combat the isolation and desperation and hopelessness that can help cause and exacerbate mental illness—schizophrenia included. The majority of Gyori’s clients are suffering afflictions like PTSD, anxiety, depression, and the associated addiction issues. That is: With treatment, they’re theoretically capable of recovery and (nonsubsidized) functioning. But Gyori’s staff is short, underpaid. New clients can’t be seen for initial risk assessment for a month. The city’s public-housing shortage is so severe that it closed the list to new applicants. “This society is set up to create Tenderloins,” she says.

“We’re dealing with the most stigmatized and misunderstood population. You can scream outside my window,” she says, turning her face in the direction of the guy screaming outside her window—something about “dinner”—”and I’m not gonna make assumptions that it’s your fault. As long as a person is disabled, and income is limited, you have to help them. Destigmatization is a big part of it.”

Sure. When I leave the clinic, it is admittedly difficult not to judge the strung-out-looking fellow lunging through the crosswalk hollering a song about monkeys, the refrain of which is a monkey call, or the parties responsible for the two piles of human shit I sidestep in as many blocks. Though an estimated 1 in 5 families contains someone with a mental illness, even families of the mentally ill aren’t always sympathetic. “We have families who aren’t willing to work with us or do anything,” says my Aunt Terri’s caseworker, Eleanor. “Your family was so willing; everybody was there to do whatever.” But she’s certainly not talking about my great-grandmother, who pronounced Terri lazy, and not even so much my grandfather, who thought his daughter was a spoiled brat who just wanted attention. And she wasn’t talking about me, whose total uselessness in Terri’s transportation and other needs earned me the resentment of at least one cousin.

Sonoma County NAMI’s David France told me about classes his organization holds for families to combat this lack of compassion. I saw a similar school talk in Ohio once as a teenager. I remember the heavyset woman well, her matching blouse and pant of some artificial peach fabric. I don’t remember whether her illness was depression or bipolar or what, but I do remember that she told us her method of self-harm was to pull out all of her eyelashes because it was a self-harm no one noticed. She told us, with the inevitably pleading look of a person who knows they’re telling you something important but also knows you can’t possibly understand, that suicide was a permanent solution to a temporary problem. That no matter how sick you are, there’s room for improving and becoming a functioning member of society, like her.

I remember finding her totally weak and disgusting.

“People with mental illness are not valued in this society,” says Roth. Not valued members of the family Christmas party. Not valued recipients of dwindling state budget dollars. “It’s not a place where people want to give money. We’re in a country right now that is so mean-spirited, people really aren’t in any mood to spend any money on anybody.”

But as Randall Hagar, director of government relations for the California Psychiatric Association, points out, the country will pay for it one way or another. “Taxpayers pay for nuisance issues related to the homeless,” he says, especially since the total elimination of California’s $55 million mentally ill homeless outreach program, which deployed teams to help with everything from housing crises to paperwork. Since the defunding of the state’s mentally ill offender crime reduction program, which delivered services like training, counseling, and outpatient assistance to discharged transgressors, the incidence of violence has increased among that population, says Hagar. In Virginia between 2010 and 2011, mental-health treatment facilities turned away 200 people determined to be dangerous because there were no available beds. In Arizona, a Phoenix hospital saw a 40 percent jump in psychiatric emergency room episodes after the abolition of mental-health services to 12,000 non-Medicaid-eligible mentally ill. The moral issues of not taking care of society’s sick and vulnerable aside, Hagar says, our post-deinstitutionalization transinstitutionalization is not cheap: “Two to three thousand dollars in treatment saves $50,000 in jail.”

In the Tenderloin—as in Santa Rosa, as in Cleveland and Phoenix and Lynchburg—”do we have the resources to adequately treat them? No,” Gyori says. Neither for those who seek it, nor for those who “don’t want your help but go bonkers in the street and have to be locked away.” Whatever differences they have over the patients’ rights debate, Torrey and Gyori agree on one thing. “Sometimes,” Gyori says, “people need to go to the hospital. The problem is, now you don’t have acute beds. So people are let go too soon, and it’s not as easy to get in.”

“The system now is, they don’t wanna see people,” Torrey complains. “None of us are suggesting that we need to go back to 1930, when I as a psychiatrist could say, ‘I don’t like the sound of your voice, so I’m going to keep you in my facility that I also happen to own for three weeks.’ You have to have a system of checks and balances.”

But the pendulum has swung far past patients’ rights and well into the territory of wild neglect. The dismantling of the mental-health system has left those willing to undergo treatment with no options, and rendered the laws to protect against dangerous scenarios ineffective. “Danger to self or others is defined too limitedly,” Torrey says. In the eight states where that’s the only triggering mechanism for treatment, “you either have to be trying to kill your psychiatrist or trying to kill yourself in front of your psychiatrist.” Some states have less-strict provisions, but even there, no open beds plus the expense of keeping someone in the beds equals admission standards that are too high and discharge standards that are too low.

Regardless of what you think about commitment rules, the bottom line is you have to have facilities. If there had been a facility—not “a psych ward in a general hospital which is set up to see people with eating disorders and depression,” Torrey says, but a clinic staffed with the appropriate kinds of professionals and with an open bed and antipsychotics that have proven to be extremely effective if properly administered—if my Uncle Mark could have taken Houston someplace like that—maybe crimes like Houston’s could be not just predictable, but preventable.

“Hospitals are motivated to get people out as quickly as possible,” says Robin Lipetzky, who deals with the fallout as chief public defender of Contra Costa County, just across San Francisco Bay. “We ignore the mentally ill until they commit a crime that ends them up in prison. Over and over again we see these situations where parents of these folks who commit these offenses—if they don’t kill their parents, which is what often happens—say they’ve been trying and trying to get treatment for these kids and it’s just not available. And it’s usually young adults. There’s not enough out there in terms of resources for families. The people making the budgets don’t look at it as an integrated whole. It’s unfortunate that that calculation isn’t done at the same time.” Although, she concedes, not all the pieces of calculating the cost of “treatment of the mentally ill up front” would be that easy to do. “How do you put the price,” she asks, “on people losing their lives when people have a psychotic break?”

“SOCIETY SHOULD BE more helpful and there should be more services, obviously,” says Lieutenant Corrado Ghioldi of the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office. But in the meantime, “we had to evolve, grow, and specialize to be able to take care of these people.” The Sonoma County jail, just a few miles away from the spas and rolling, vineyard-lined hills that make the region world famous, is an expensive-looking salmon-colored facility hidden from the street by manicured trees. (“Is this the new Nordstrom?” people drove up to ask when it was first built.) Ghioldi has spent a career trying to better serve his jail’s mentally ill population, which has increased 3,650 percent since 1992, and which now includes Houston. “We’re slowly turning into a big mental-health facility. I never could have imagined this 20 years ago,” he says. And then, more to himself, with something approaching awe, “What’s it gonna be in 10 years?”

The jail has animal-assisted therapy now. An independent-living course. Their “Prevention, Art & Anger Management, Thinking Cognitively, Health Issues, Stress Reduction (PATHS)” program won an award in 2011 from the Council on Mentally Ill Offenders. An unusually dedicated corrections deputy who’s even joined the local NAMI board, Ghioldi convinces the deans of nearby universities to come teach recidivism-reducing classes by offering to go give university students presentations in exchange. “We wouldn’t survive without volunteers because we don’t have the money to run all these classes,” he says.

Houston, who had already been incarcerated for 430 days the first time I visited him back in January, costing the county $49,811 in jail expenditures alone, won’t go to any of the classes. He gets medication, but no therapy. After I identified myself as a cousin who knew Annette and we settled into our visiting-booth chairs, he explained, without complaining, that he wasn’t exactly thriving here. He talked about his illness a little, how he’d had “some episodes” that had landed him in the most acute cells of the most serious of the jail’s three mental wards, “the dungeon,” which includes rooms with padded walls and no socializing and barricadable windows and sometimes sick people yelling and screaming on all sides. “You would have a nervous breakdown,” he told me, “just standing in there for 10 minutes.”

It was quiet as a library when I later visited the unit and interviewed some of the deputies, whom Ghioldi handpicks and specially trains to work in the psych units, 35 mental-health officers in all. Though they were decidedly not doing what they signed up for at the police academy, each spoke sensitively and passionately about their wards and asserted, to a man, that working with this population was the most rewarding career on the force. Meanwhile, the faces and naked chests of crazy inmates appeared through the long vertical windows of the reinforced metal cell doors.

During the 45 minutes that I got Houston out of his cell, mostly what he wanted to talk about was books. Superfriendly but often avoiding my eyes and pulling his jaw down, he was ceaselessly ticky and fidgety, common side effects of the antipsychotics he’s on. He told me he was reading Bertrand Russell—Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits—and when I said I couldn’t really hang in that philosophy discussion, he switched to poetry. When I chastised him for reading hardly any books by women, he smiled, looking embarrassed, and promised to read whatever I sent. He wanted to know what my college thesis was, and asked me a lot of questions about it.

We did not talk about Uncle Mark, or the 500 people who went to his memorial thanks in part to the 35 years he’d spent mentoring in AA. We didn’t talk about how Houston had so gruesomely killed him, or, as unspeakable as that was, that sometimes unchecked illness can lead to far worse, given access to guns plus delusions about a movie theater or a temple or an elementary school. We did talk about the possibilities for Houston’s own life. After more than a year of evaluations, in which several psychiatrists declared Houston schizophrenic, it still wasn’t clear if the DA’s office would pursue a murder trial or if Houston might be sent to the psych hospital in Napa for treatment and possibly eventual release.

“I might get into politics,” he said when I asked him what he’d do if he ever did get out. “Like work in an organization, not just standing around getting signatures.” Or “help people in my situation.” Someday, he said, he’d really like to travel. He asked me a lot of questions about what it’s like to travel, eyes big behind his glasses; he said he also liked the idea of teaching abroad, like another cousin in Abu Dhabi, where the prince shuts down the highway to show off his fantastic cars.

It’s different, obviously, because no matter what happens to Houston, and on top of whatever else he has to overcome, he’ll always have done what he did. But I told him about Aunt Terri anyway. How she’d prevailed after she stayed on her meds and got a good caseworker and a place of her own, even though she was much lower-functioning and less lucid than he is. How it seemed that she’d found joy in her interests—music, smoking, collecting cat figurines. And in family. When she was cleaning out the trailer, Paula found Terri’s diary, and in addition to brief, sweet poems, it was full of updates about our lives. On one page, under the heading MY CHILDREN, appeared many names. Some were of babies who did not exist. Some were my cousins’. One was my own.

I told Houston about as many happy endings as I could think of. I told him about the therapeutic community I’d seen in Ohio that was way more effective than institutionalization, though not covered by Medicaid, a working farm with Belgian horses and beautiful Belted Galloway cows and programs to help residents better integrate into society. When he looked impressed, I didn’t tell him they don’t accept people who’ve committed violent crimes.

“I told Houston once that my hope for him is that he can deal emotionally with what he’s done,” killing his dad, his biggest fan, his best supporter, says Fred Von Renner, a family friend who visits the jail every week. “Houston has told me he hopes he never goes to that place again, where he hears voices that say his parents are against him,” where he’s overcome by darkness. “I told him I hope he can go to Napa, get out, get the right level of medication, get a life, a family. ‘That’s the hope I hold for you,’ I told him.”

“With Houston,” my grandmother, on the other hand, admits, “I’m on the fence. You can’t proclaim him well because you can’t guarantee that this man will go out in the world and take his medication. If he takes it, fine. He’ll do fine. But if he’s noncompliant? Can a person like this be trusted? That would be my fear.”

The last time I saw Houston was in a courtroom at the end of February. It was yet another hearing, to set his trial date, now slated for April 5. He didn’t look at me, or at anybody, not even his mother, Marilyn, as she stood in the audience, yelling, “He’s gonna die if he stays here more. He’s gonna commit suicide.” He kept his tortured-looking face pointed at his twitching thumbs, probably wondering, amid his delusions—despite the antipsychotics, he still sees people hiding in the corners in the dark, still suspects people of being conniving extraterrestrials or robots—if, when the trial moves forward, his NGI plea—not guilty by reason of insanity—will be accepted by a jury. Whether he will go to prison, or—after likely waiting another six months in jail for a bed to open—instead be sent to Napa for treatment and stay there for years, or forever, occupying one more precious bed that won’t be available to one more guy having trouble until it’s too late.

“I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve seen this kind of situation leading up to somebody killing somebody,” says Lipetzky, the Contra Costa County public defender. “I have two NGI clients right now who tried to kill their parents,” Eleanor says. “One of them even had ’em tied up and everything” when the parents were able to talk their child out of it. If we don’t talk about the whole, true picture of untreated mental illness, Torrey says, so that we can treat it, the far-from-standard but still very real possibilities for violence from a judgment- and impulse-impaired brain, “the stigma’s going to go on forever because of the high-profile homicides that cause the stigma.”

“Once Houston is finally hospitalized and treated,” my Aunt Annette says, “maybe Mark will finally be able to truly rest.” And if that doesn’t happen, at least—at the very least—”his story can go to a greater cause. I want people to know about this,” she says, with a sharp, gasping cry. That’s why she’s telling me, and I am telling you: “If this story can serve a purpose, I feel like Mark will not have died in vain.”