Cluster of hibernating gray bats (Myotis grisescens):Image courtesy of <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/usfwshq/">US Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters</a> via <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/usfwshq/5687233991/">Flickr</a>

The US Fish and Wildlife Service confirms white-nose syndrome (WNS) is present at Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama. This cave provides winter hibernation space for several bat species, including the largest documented wintering colony of endangered gray bats. More than a million individuals of this federally listed and IUCN listed species nest at Fern Cave.

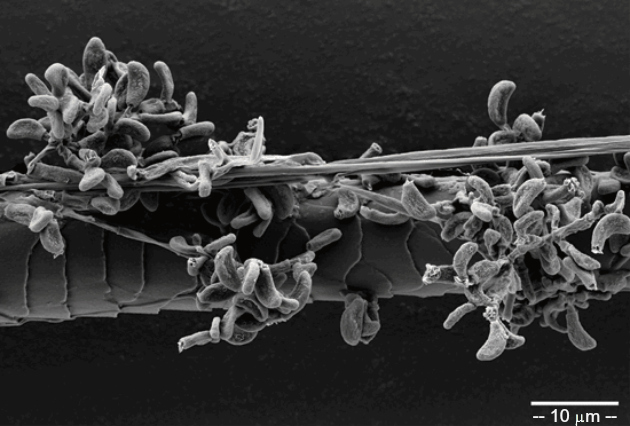

White-nose syndrome—a fungal disease possibly imported from Europe on the boots of spelunkers (cave explorers)—hits bats at their winter hibernation roosts. It was first identified in North America in New York in 2006/2007 and has since spread to 22 states (more on that here) and five Canadian provinces. WNS has decimated bat populations with mortality rates reaching 100 percent at some sites. In the northeastern United States, bat numbers have plummeted by at least 80 percent, says the USGS, with ~6.7 million bats killed continent wide. The Center for Biological Diversity reports that biologists consider this the worst wildlife disease outbreak ever in North America.

“With over a million hibernating gray bats, Fern Cave is undoubtedly the single most significant hibernaculum for the species,” says Paul McKenzie, Endangered Species Coordinator for USFWS. “Although mass mortality of gray bats has not yet been confirmed from any WNS infected caves in which the species hibernates, the documentation of the disease from Fern Cave is extremely alarming and could be catastrophic.”

Strong words for a government agency. But the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) is even more pissed off. “With white-nose syndrome wiping out bats across the eastern United States, it should be all hands on deck,” says Mollie Matteson, a CBD bat specialist. “But tragically the response to this crisis continues to be lackluster. [Bats are] supremely important for farming, for our food security. They eat thousands of tons of insects, including crop pests, every year.”

The CBD says researchers estimate the economic value of bug-eating bats to American agriculture at $22 billion, maybe as much as $53 billion a year. Yet federal funding for WNS research and disease response coordination has been scarce the past several years and is likely to become even scarcer in the 2013 and 2014 federal budgets.