IN 2005, SAM ALLISON, a Tennessee housepainter in his 30s, arrived at Daniel Hoover Children’s Village, an orphanage outside Monrovia, Liberia. He’d come to adopt three children, but ended up with four: five-year-old Cherish; her nine-year-old brother, Isaiah; their 13-year-old sister, CeCe, who had taken care of them for years; and Engedi, a sickly infant whom Sam and an adoption broker had retrieved from “deep in the bush.” The older children’s father had sent them to Daniel Hoover during Liberia’s 14-year civil war, after their mother died in childbirth. The orphanage, run by a ministry called African Christians Fellowship International, often ran short of food, and schooling was sporadic. The children, who were forced to flee temporarily when rebels attacked the facility in 2003, referred to America—whose image looms large in a country colonized by freed slaves in the 19th century—as “heaven.”

In Tennessee, Sam and the four adoptees joined his wife, Serene—a willowy brunette who’d attempted a career in Christian music—and their four biological children. Together they moved into a log cabin in Primm Springs, a rural hamlet outside Nashville. Serene welcomed the children with familiar foods such as rice, stew, and sardines, and they were photographed smiling and laughing.

The cabin adjoined a family compound shared by Serene’s parents, Colin and Nancy Campbell, and the families of Serene’s two sisters. Colin is the pastor of a small church and Nancy a Christian leader with a large following among home-schoolers. Her 35-year-old magazine, Above Rubies, which focuses on Christian wifehood, has a circulation of 130,000 in more than 100 countries—mostly fundamentalist Christian women who eschew contraception and adhere to rigid gender roles. The aesthetic is somewhere between Plain People austerity and back-to-the-land granola, with articles like “Plastic or Natural?,” “Raising Missionaries,” and “Green to Go,” featuring recipes for concoctions like “green transfusion” and “My personal earth milk.” In a Facebook photo, Nancy twirls in a tie-dyed peasant skirt. Her daughters, striking women with waist-length hair, use Nancy’s magazine to peddle motherhood-themed CDs and health and lifestyle books with titles such as Trim Healthy Mama. It’s an extended family that thousands of home-schooling mothers know nearly as well as their own.

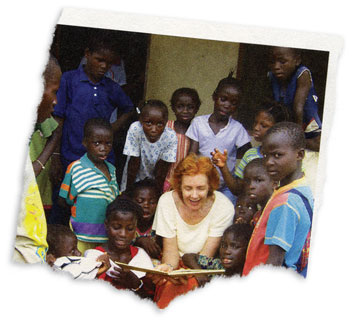

In 2005, Above Rubies began advocating adoptions from Liberia, arranged through private Christian ministries. Campbell—whose magazine likened adoption to “missions under our very own roof!”*—spent a week visiting Liberian orphanages and returned with “piles of letters addressed ‘To any Mom and Dad.'” She touted the country’s cost-effectiveness—”one of the cheapest international adoptions”—and claimed that 1 million infants were dying every year in this nation of fewer than 4 million people. “When we welcome a child into our heart and into our home,” she wrote, “we actually welcome Jesus Himself.”

Campbell urged readers to contact three Christian groups—Acres of Hope, Children Concerned, and West African Children Support Network (WACSN)—that could arrange adoptions from Liberian orphanages. At the time, none of these groups was accredited in the United States as an adoption agency, yet they all placed Liberian children with American families for a fraction of the $20,000 to $35,000 that international adoptions typically cost. Before long, members of a Yahoo forum frequented by Above Rubies readers were writing that God had laid the plight of Liberian orphans heavy on their heart. “Families lined up by the droves,” one mother recalled. They “were going to Liberia and literally saying, ‘This is how much I have, give me as many as you can.'”

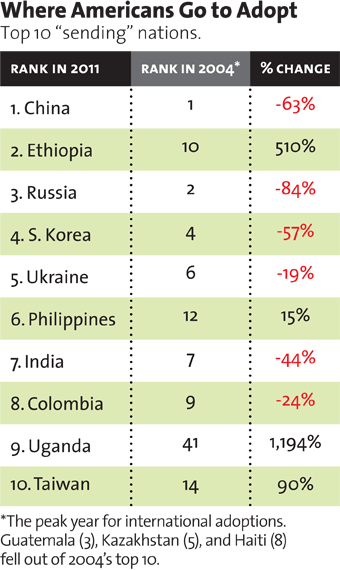

The magazine’s Liberia campaign, it turned out, heralded an “orphan theology” movement that has taken hold among mainstream evangelical churches, whose flocks are urged to adopt as an extension of pro-life beliefs, a way to address global poverty, and a means of spreading the Gospel in their homes. The movement’s leaders, as I discovered while researching my upcoming book on the topic, portray adoption as physical and spiritual salvation for orphans and a way for Christians to emulate God, who, after all, “adopted” humankind. Churches reported that the spirit was proving contagious; families encouraged one another to adopt, and some congregations were taking in as many as 100 children. Dozens of conferences, ministries, and religious coalitions sprang up to further the cause, and large evangelical adoption agencies such as Bethany Christian Services reported a sharp increase in placements at a time when international adoptions were in decline.

Within months of launching her Liberia campaign, Campbell reported to her readers that 70 children were in the process of being adopted through African Christians Fellowship International, most to families that were already large, with some taking as many as five or six. She recalled helping one adoptive father navigate Washington, DC’s Dulles airport with his new Liberian triplets; she put one of them, a wide-eyed infant named Grace, with bow lips and a Peter Pan collar, on the cover of the magazine. Campbell adopted four children herself, and Serene took a total of six. “From my article in Above Rubies about the children in Liberia there must have been up to a thousand children adopted,” Campbell informed me in an email, “and most have been a blessing.”

FOR PATTY ANGLIN, the cofounder of Acres of Hope, one of the groups promoted by Above Rubies, the campaign’s impact and Campbell’s characterization of the adoptions as “cheap, easy and fast” proved jarring. “So many people responded, and they were responding at an alarming rate,” she recalled.

In part, Anglin was worried because she knew how complicated things could get in Liberia, a nation that had only recently emerged from its civil war and was still in a state of near lawlessness. Given the conditions there, the prospect of a $6,000 adoption fee was enough to attract some shady operators. Adoptions that took a year to process in other countries could happen in weeks or days in Liberia, and bribery was rampant. Liberian parents began complaining that adoption had been misrepresented to them as some sort of temporary education arrangement—one local orphanage staffer proclaimed that his own children had been adopted and were now “benefiting from the program,” according to AllAfrica.com. WACSN, one of the agencies Campbell promoted, would eventually host a contingent of American preachers for a three-day revival in Monrovia. The organizers urged believers back home to get involved by adopting through WACSN, which had declared that it would only serve biblical literalists. The struggling Liberian government was able neither to keep tabs on children leaving the country nor to distinguish licensed adoption agencies from groups that merely had nonprofit status.

All was not harmonious in Primm Springs either, according to the four Allison adoptees I interviewed at length for this story. (Sam Allison has denied all of their allegations.) “Everything was good for a month,” CeCe, now 21, told me. “We got to the next month and things started to get a little weird.” Serene’s raw-food offerings were unfamiliar, but Sam would discipline them if they balked at eating her meals, the children said. Other cultural impasses included the children’s use of Liberian English and the Liberian prohibition on children looking adults in the eye. “They’d say, ‘You are so rude. I’m talking to you!'” CeCe recalled. “They expected us to adapt in a heartbeat.”

In October 2006, a year after their first Liberian adoptions, the Allisons adopted another pair of siblings: Kula, 13, and Alfred, 15. “In Africa we thought America was heaven,” recalled Kula, who is 19 now. “I thought there were money trees.” Primm Springs was a rude awakening: It was dirty, she recalled, and she had no toothbrush. The new house Sam was building—with the older kids working alongside him—often lacked electricity. There was only a woodstove for heat, and no air conditioning or running water yet. Toilets were flushed with buckets of water hauled from a creek behind the house. The children recalled being so hungry that they would, on occasion, cook a wild goose or turkey they caught on the land. “We went from Africa to Africa,” CeCe said.

*Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly cited Nancy Campbell as the source of this quote. These were the words of a different writer in Above Rubies.

They didn’t attend school, either; home schooling mostly consisted of Serene reading to the younger children. When the older kids watched a school bus drive past on a country road and asked why they couldn’t go, they were met with various excuses. So Isaiah and Alfred worked with Sam in his house-painting business or labored in Nancy Campbell’s immense vegetable garden while CeCe, Kula, and Cherish cleaned, cooked, and tended to a growing brood of young ones. It was also the job of the “African kids,” as they called themselves, to keep a reservoir filled with water from the creek. CeCe hadn’t yet learned to read when Serene gave her a book on midwifery so she could learn to deliver their future babies. “They treated us pretty much like slaves,” she said. It’s a provocative accusation, but one that Kula and Isaiah—as well as two neighbors and a children’s welfare worker—all repeated.

Discipline included being hit with rubber hosing or something resembling a riding crop if the children disrespected Serene, rejected her meals, or failed to fill the reservoir. For other infractions, they were made to sleep on the porch without blankets. Engedi, the toddler, was disciplined for her attachment to CeCe. To encourage her bond with Serene, the Allisons would place the child on the floor between them and CeCe and call her. If Engedi went to CeCe instead, the children recalled, the Allisons would spank her until she wet herself.

Sometime in 2007, Serene began asking the adopted kids whether they had been sexually abused back in Liberia. This was becoming a panicked theme on Liberian adoptions forums, as sexual “exploration” and abuse at some of the orphanages came to light. Serene accused CeCe of tempting her husband, and, according to the children, began flirting with Isaiah in ways that made them feel uncomfortable. Later, after Isaiah admitted that he had kissed and lain on top of one of the Allisons’ biological daughters, four years his junior, the local Department of Children’s Services registered a sex abuse report and the family was instructed to keep the boys in a separate bedroom.

In September 2007, Serene wrote a cryptic essay for Above Rubies about situations mothers might face “that seem out of your control or even out of your children’s control.” The magazine, which had previously resembled a doting grandmother’s scrapbook, began mentioning the Liberian children less and less frequently, but they were there between the lines as Campbell wrote about the need for strict discipline to bring about harmony in the home. “If you have to have a little war before you have peace,” she wrote, “don’t be afraid.”

The Liberian kids weren’t the only ones questioning their lot. I spoke with Rachel Johnston, a 28-year-old from Louisiana who arrived at Primm Springs in 2007 as an Above Rubies intern—one of many home-schoolers who signed up as “Rubies Girls.” “I had only been there about a day when I realized that things weren’t really right,” she said. For one, she saw the Allisons and the Campbells refer to To Train Up a Child, a book by fundamentalist preacher Michael Pearl and his wife, Debi, that advocates strict physical discipline starting when children are less than a year old. The book, which has sold nearly 700,000 copies, promises that “the rod” (the Pearls suggest flexible plumbing supply line) will bring harmony to a family in chaos, creating “whineless” children who have learned to submit. “Somehow, after eight or ten licks, the poison is transformed into gushing love and contentment,” they write. “The world becomes a beautiful place. A brand new child emerges.”

While Nancy Campbell insisted she “never adhered” to the Pearls’ book with any of her children, her own writings stress the need for obedience in the home: “It is amazing how peaceful and happy a child can be after they have received a good spanking,” one column reads. Pearl, whose teachings have been at issue in the deaths of several adopted children, told me his methods are not as effective with older children or adoptees from other cultures. Chuck Joyner, the assistant general manager for Pearl’s ministry, No Greater Joy, said the organization had heard from some of the hundreds of people who had adopted from Liberia. “Many, if not the majority, of the families encounter problems so severe that they had to give up the children,” he said. Pearl worried on his website that some of his followers’ Liberian children were “well-versed in all the dark arts of eroticism and ghastly perversion.”

Online, parents began writing that their adopted children were manipulative and wild, compulsive liars or thieves, and sometimes violent. “There are two languages in Liberia,” wrote one mother, “English and lying.” Families described the distressing ways the kids reacted to reprimands, from unresponsive pouting to uncontrollable wailing. Some regarded it as manifestations of PTSD, while others saw defiance. The adoptions began to fail.

“Many adoptive families were not prepared for the devastation that these children were suffering from,” acknowledges Acres of Hope’s Patty Anglin—the memories, in some cases, of extreme violence, relatives killed, corpses in the street. These were “good, good families,” she adds, “but oftentimes they have the heart, but not necessarily the background or education to understand what is involved.”

Yet the scope of the failure suggested another problem: With so many adoptees going to families for which attachment and love were defined as immediate obedience, it was a mismatch of children’s needs and parents’ propensities on an epic scale.

IT WASN’T JUST Above Rubies readers catching the adoption bug. In 2007, the Christian Alliance for Orphans, which took root around the same time Campbell published her first adoption articles, held a pivotal meeting at the Colorado headquarters of James Dobson’s Focus on the Family; pastors emerged ready to preach the new gospel of orphan care and adoption, according to an account in the Los Angeles Times. Focus was soon predicting that, within a decade, it would be “pretty uncommon” for Christians “to not adopt or not care for orphans.”

Indeed, just two years later the Southern Baptist Convention, America’s largest Christian denomination save the Catholic Church, passed a resolution calling on its 16 million members to get involved, whether that meant taking in children themselves, donating to adoptive families, or supporting the hundreds of adoption ministries that were springing up around the country to raise money and spread the word. Neo-Pentecostal leader Lou Engle also called for mega-churches to take on the cause, which would give them “moral authority in this nation.”

The movement spawned numerous conferences and books built around the idea that adopting a needy child is a form of missionary work. “The ultimate purpose of human adoption by Christians,” author Dan Cruver wrote in his 2011 book, Reclaiming Adoption, “is not to give orphans parents, as important as that is. It is to place them in a Christian home that they might be positioned to receive the gospel.” At an adoption summit hosted by the Christian Alliance for Orphans at Southern California’s Saddleback Church, pastor Rick Warren told followers, “What God does to us spiritually, he expects us to do to orphans physically: be born again and adopted.”

Families wrote about their “adoption journeys” in blogs with names such as Blessings From Ethiopia or Countdown 2 Congo and raised money for their adoption fees by soliciting donations or selling T-shirts. Describing herself as “a dumpster diving orphan lunatic,” a mother wrote that she was still “afflicted with my Orphan Obsession” after bearing two kids and adopting four more. One ministry declared simply: “Adoption is the new pregnant.”

All of this enthusiasm has created an army of advocates rallying to revive an international adoption business that has been on the wane since 2004, and has reoriented the industry in a more overtly religious direction. Of the 201 accredited adoption agencies listed with the State Department, more than 50—including many of the largest—are explicitly Christian (not counting the Catholic agencies). Still more use religious imagery or language on their websites or partner with evangelical groups. “I adopted in 2001 and there was none of this, but I noticed the creeping religiosity since then,” said Karen Moline, a board member for the watchdog group Parents for Ethical Adoption Reform. “On adoption forums, people started signing their messages, ‘Blessings,’ and there would be pictures of children from a Third World country saying, ‘Lost souls.’ The fervor is unparalleled.”

In 2010, a year when international adoptions overall fell by 13 percent, Bethany Christian Services—one of the nation’s largest agencies, with adoption-related revenues of around $25 million—announced that its placements were up 26 percent and international placements were up 66 percent for the first six months. Adoption inquiries had nearly doubled. Bethany’s numbers have since declined in tandem with the fortunes of the industry, but the countries still experiencing adoption booms—among them African nations such as Ethiopia, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—have been the focus of intense missionary activity. “I think if evangelicals weren’t driving a lot of the adoption business, there would be no international adoption, period,” Moline said.

While these families clearly aim to help, the “orphans” they hope to save are a complicated group. Many come from countries where orphanages are essentially the child welfare infrastructure that families turn to in times of need. In some instances, children have been fraudulently passed off as having no family; in others, children with intensive needs, whether emotional or medical, have ended up in homes unequipped to handle them. Although reliable numbers are hard to come by, it is estimated that 6 to 11 percent of all US adoptions fail, with the number climbing to nearly 25 percent for children adopted as adolescents. Failed international adoptions have become so common that a panel on the subject at the 2012 Saddleback summit drew one of the largest crowds of the conference.

THE ALLISONS, for one, had bit off more than they could handle. The remainder of their story, as the children recalled it, went something like this: One morning in the spring of 2008, Serene and CeCe quarreled over dishwashing, and CeCe ended up leaving home with her suitcase. “I told her, ‘I’m sick of everything that you guys have been doing to us,'” she later recalled. “‘You don’t send us to school, you don’t feed us the right food.'” When she came back to fetch her siblings, CeCe said, Sam shoved her to the ground.

That night, Sam brought CeCe and Kula, who also had been running afoul of Sam’s discipline, to stay at the home of a woman they knew from church until the Allisons could figure out what to do with them. But when she heard the girls’ stories, the woman helped them call the Department of Children’s Services. There was a court hearing, and Kula, along with Alfred, who had turned 18, were sent to live with their uncle, a Liberian immigrant, in eastern Tennessee. CeCe was bounced to Sam’s sister’s place and then to the North Carolina home of the director of the Daniel Hoover orphanage. She felt homeless, she told me, “like a street dog that nobody cared about.”

In the end, the Allisons delivered CeCe to the Atlanta home of Kate and Roger Thompson, old friends of the Campbells; it was meant to be a temporary stay before sending her to a home for troubled girls. Kate is a Christian singer-songwriter with an album about adoption who had once cared for Serene and her sisters while their parents went on a mission. She has 14 children, 8 of them adopted through foster care. And while the Thompsons differed with the Allisons on parenting, Kate recalled feeling sorry for Serene: “She was barely in her 30s, trying to deal with teenagers with horrendous issues from living in a war zone.” But her view began to change a few months later when Serene called to say they were sending CeCe’s brother, Isaiah, then 13, back to Liberia. Serene had caught him watching her in the shower.

The Thompsons begged them to reconsider, to send Isaiah to counseling instead. They also called Children’s Services, which, according to Kate, warned the Allisons that it could be illegal to repatriate Isaiah. But Sam and Serene sent him off anyway. “They told me, ‘If we told people about what you did, they’d put you in jail,'” Isaiah told me later. “I felt so bad, I didn’t even care.”

When Isaiah and his escort, a man Sam knew, arrived in Monrovia, they found the orphanage closed. The escort left him instead with a pastor who cared for street children. Isaiah begged the man not to leave him behind. He had only a backpack of clothes and $40—and his green card would expire in six months if he remained in Liberia. He spent three weeks scavenging for food, until his great aunt found out he was in Liberia and brought him home to River Cess, a desolate coastal outpost where he could no longer understand the Kru language his cousins spoke. Isaiah felt safe, at least, but food was scarce, and he took to sleeping most of the day to escape his hunger. He also contracted malaria, as did a five-year-old cousin, who died one night by his side. “To stop myself from crying,” he told me, “I would think that what I did was really bad, and this is the least I can do.”

Frantic, Kate and Roger Thompson eventually tracked down Isaiah in River Cess and brought him back to Atlanta. Shortly before they did, the Allisons emailed Isaiah in care of Acres of Hope, assuring him that they had forgiven him, as well as the Thompsons, “for this interference…Remember the beautiful times we had together, remember we loved you always. No one can ever take away the truth of what really happened here.”

Isaiah had a printout of the email on him when he arrived in Atlanta 20 pounds lighter and suffering from PTSD. He hadn’t read it. During his four years at the Allisons’, he hadn’t learned how.

ULTIMATELY, all but 3 of the Campbells’ and Allisons’ 10 adoptions ran into serious problems. They were purged for a time from Campbell’s website, prompting readers to gossip about the family’s “disappearing children.” In a 2009 video, Serene claimed that the missing adoptees were off at school. Campbell’s biography was amended to say she had adopted “some” Liberian children.

In response to specific questions for this story, Sam Allison responded with a blanket email dismissing the children’s allegations as “lies and untruths.” Nancy Campbell conceded that Serene “did have some problems with her older children (who were adults) and wanted their independence immediately…She embraced these children as though they were from her womb and it was terribly painful for her to be rejected by them.” Only one of her own adoptions failed, Campbell said.

The Campbell-Allison clan was hardly the only one struggling. The Liberia forums were overflowing with tales of failed adoptions, most of them involving placements facilitated by the Christian brokers Campbell endorsed.

Some ended in tragedy. In 2008, Kimberly Forder, a Washington woman whose adopted eight-year-old boy had died of pneumonia in 2002, pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Prosecutors blamed his death on her systematic abuse, alleging in court documents that Forder starved the boy (he ate dog food) and made him sleep in a crib. One punishment reportedly consisted of dunking his head in a bucket of water used to clean dirty diapers. This was the same family Nancy Campbell escorted through Dulles with their Liberian triplets—adoptions arranged by WACSN after the eight-year-old’s death.

In 2010, a county court stripped a Mennonite Brethren family in Fairview, Oklahoma (WACSN also had ties to the Mennonites, most of whom are not evangelical), of custody of four Liberian sisters. Penny and Ardee Tyler had been convicted of felony child abuse for, among other things, tying one of their adopted kids to a bedpost for two nights, and leaving her outside in the cold; their adult son was convicted of rape by instrumentation.

The next year, Kevin and Elizabeth Schatz, a home-schooling California couple adopting through Acres of Hope, admitted to beating one of their three Liberian daughters, seven-year-old Lydia, to death for mispronouncing a word. In their home was a copy of Michael Pearl’s To Train Up a Child. “You must know that they did not kill their children with the little switches that we advocate using,” Pearl said, in reference to several fatal incidents. They were “locking them outdoors, giving them cold baths, denying them foods, and beating them mercilessly. There’s nothing in our literature that would suggest anything like that.”

Stories also began to pile up about children who had been returned to Liberia. “You heard about the Tennessee case that returned the child to Russia?” Edward Winant, former vice consul in charge of adoptions at the US Embassy in Monrovia, asked me when I visited the country for my book. “We’ve had at least three similar cases.” One girl, no more than 10 years old, was found wandering around the airport with $200 in her pocket.

I also met Bishop Emmanuel Jones, a Liberian evangelist who runs a home for street children. He has taken in three returned adoptees and says he knows of at least five others. Most are boys who have displayed sexual behavior or girls who “don’t want to submit,” he said. It’s hard to say what happens to other “rehomed” Liberian children because disrupted adoptions are poorly tracked, and many times the children simply drop off the map. At one point the Liberia forums were abuzz with adoptive and foster parents seeking new homes for their children. Some families called for suspending judgment of parents coping with failed adoptions, which were beginning to seem almost a routine part of the process. “Let’s be a community of support for ALL adoptions,” wrote one poster, “in any aspect of their journey.”

CECE NOW LIVES with her husband, Samuel, a fellow Daniel Hoover adoptee, and Sammy, their toddler, in a modest apartment complex in a suburb of Charlotte, North Carolina. Samuel’s sister, who was also adopted, lives there as well. Charlotte is a hub of Liberian adoptees; Samuel, a slim and quiet 23-year-old, was part of a touring boy choir adopted, almost in its entirety, to local families—the heartwarming story of the “Hallelujah Chorus” was featured in Oprah’s O magazine. When he and CeCe married, in 2011, all of her bridesmaids were Daniel Hoover alums, and a good number of their friends were children from adoptions that fell apart. “Most of us, when we came to America, there was some part of us that a lot of adoptive parents didn’t understand, that we would never be the same like their own kids,” CeCe said.

Samuel works days at a Tyson chicken processing plant where CeCe began working nights when their baby was about a year old. She also tries to supplement their income with a direct-sales jewelry business. She applied to cosmetology school but didn’t have adoption papers to prove her citizenship, nor full educational records. CeCe had asked the Allisons for them, but for close to four years they wouldn’t return her calls.

It turned out the Allisons had neglected to complete the stateside adoption process, thus jeopardizing the legal residency of some of the children—as Kula discovered during her 2011 readoption by Pam Epperly, a longtime Tennessee foster mother. “Kula made disclosures that disturbed our court staff as well as the judge,” a representative from a Tennessee children’s service provider told me. The rep alerted the Department of Children’s Services, which opened two cases on the Allisons but closed one of them after the remaining children did not disclose any abuse. Several months later, with the other case still pending, the Allisons left the state. Unable to track them down, DCS ended its investigation.

At some later point, the Allisons apparently returned to Tennessee. In the summer of 2012, hoping to keep tabs on her kid sister, CeCe sent them a message on Facebook. Alfred had already reconnected with the family, and when CeCe asked to see Cherish, she heard back at long last. Sam and Serene asked if she was “ready to move on and let God take control of things.”

Last September, for the first time in years, CeCe returned to the Allisons’ home. Cherish was nearly a teenager, and Engedi, who hadn’t been talking when CeCe left home, was a big girl now. Sam cried and Serene apologized. CeCe posted a Facebook picture of Serene holding baby Sammy (“First grandchild!”), and before long she had resumed friendships with the entire Campbell clan. When she returned for Thanksgiving, Alfred and Kula came too.

The turnaround doesn’t surprise the social-services worker who asked DCS to investigate the family. It’s like battered wives syndrome, she told me. “If the children at any point established a connection, they’re going to want to return…Even though it ended badly, it’s still a connection.”

IN 2009, LIBERIA imposed an emergency moratorium on international adoptions, citing “gross mismanagement.” The move came in response to a tense child-trafficking dispute between the government and Addy’s Hope, then an unlicensed Texas agency whose clients, the government said, did not have permission to take children out of the country. (Addy’s Hope disputes this.) The agency’s representatives had rushed a group of seven children onto a plane, evading the British NGO Save the Children and Liberian officials who tried to stop them. It was the last straw for a problem-plagued program.

During my 2011 trip, I visited Addy’s Hope’s old orphanage. In a bare but tidy concrete building, pastor Baryee Bonnor and his wife were still caring for 19 children left in limbo by the moratorium. The American parents who had intended to adopt “stopped supporting them when adoptions closed,” he explained, and few of the Liberian parents had returned to reclaim their children.

Now Liberia is poised to reopen for overseas adoptions, supposedly under more stringent requirements. Thus far, only three agencies have been approved to work in the country. One of them is Acres of Hope, which now partners with a licensed agency and also has begun arranging adoptions from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On my very first night in Monrovia, as I ate at a hotel restaurant popular with expats and development workers, a Christian Lebanese logging executive came to my table. When I told him why I was there, he asked if I wanted to adopt a child, and offered to take me the next day to the interior, where he would help me find a baby to bring home. I declined, but he remained excited by the prospect, and was already forming a plan. “They all need adoption,” he said, his eyes growing misty. “It would be viewed as a miracle.”