Tucked away in the basement of the Russell Senate Office Building is a small, secretive corner of the upper chamber of Congress. No interviews with staff are permitted. Photography is not allowed inside and film crews are barred. Virtually all inquiries from journalists are shot down. As one employee furtively explains when I visit the facility, “We’re not allowed to talk about anything that goes on here.”

This is Senate Hair Care Services, the official barbershop and salon of the world’s greatest deliberative body. To reach it, customers must navigate past the office of freshman Arizona Sen. Jeff Flake, a canteen, the air-conditioning division, and a cluttered message board advertising guitar lessons and martial-arts classes. The joint is lined with creaky wooden chairs and features a shoeshine station that looks like it fell out of the 1930s. The walls are decorated with photographs and head shots of current and former senators, including Barack Obama, Joe Biden, John Glenn, and John F. Kennedy. A basic trim goes for $20. The “Royal Treatment Facial and Shave” costs $30. A perm is $75.

Lately, the barbershop has taken heat for its cost to the American taxpayer—and a renewed push to privatize has begun. “It’s time,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), a longtime client of the salon, told the New York Times. “In fact, I was talking to some of my friends there the other day, and they said they recognized too that the time has come.”

When I stop by on a Friday afternoon, a manicurist takes me into a corner and asks me what I’d like.

“Give me what John Kerry used to get! Or give me ‘The Ted Cruz.’ Or…how do you do Kelly Ayotte’s nails?” She chuckles and gently reminds me that she can’t discuss which famous cuticles she has or hasn’t buffed and polished.

“Just make me look fabulous” is all I can think to say. I decide to go with a simple $18 manicure. As the manicurist soaks my hands, she insists that I’ll be able to see my reflection in my fingernails “for days!”

The salon’s high-profile fans are more forthcoming, mostly about longtime top barber Mario D’Angelo. “I call him the butcher. He is a butcher, and I’ve got the scars to prove it,” McCain, a regular since his days serving as the Navy’s Senate liaison in the late ’70s, told the Daily last year. D’Angelo used to dye the hair of long-serving South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond. The senator’s wife “and the girls in the office always wanted it lighter, sort of a more natural look,” D’Angelo told the author of the book The Centennial Senator. “So we tried to do what he wanted one month, and then the next month we would satisfy the ladies. That’s why we kept changing the shade of his hair. It went back and forth from a light brown to a dark blonde. He always said, ‘I want it darker.’ Sometimes he would say ‘black’; I know he didn’t mean black.”

The salon caters to senators, their staffers, and even interns, though outsiders who seek it out are welcome. But there’s a scheduling hierarchy: If a senator (or a more powerful senator) wants your slot, you could be bumped. Suppose New York’s Chuck Schumer, the Senate’s third-ranking Democrat, needs a trim at 9:30 a.m. but Wyoming’s Mike Enzi, a three-term Republican who occupies no major leadership positions, has reserved the spot. The gentleman from Wyoming will have to yield.

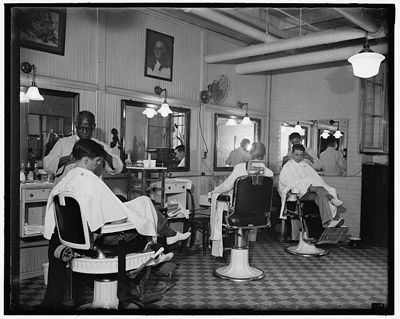

The barbershop, which was housed in the Capitol until the mid-’70s, has groomed senators for more than 150 years. For most of that time, it was just another boys’ club perk, along with the complimentary, personalized gold-trimmed porcelain shaving mugs it distributed to all incoming lawmakers. An 1893 newspaper article reported that “three colored barbers” tended to the clients, who could also receive a massage or relax in a steam box that was “just big enough for the fattest possible Senator to get into.” Haircuts and shaves were free, though some senators resisted the idea of tipping.

Only senators were allowed back then, and as now, the service was discreet. Asked about his partisan leanings, 83-year-old barber John Simms reportedly told a nosy senator in 1928, “Oh, g’way, don’t ask me that.” Besides, he added, “No resident of Washington can vote anyway.” (Simms’ ghost is said to haunt the Capitol corridors.) The shop maintained a private room where lawmakers could make calls or hold meetings while getting a trim. “I heard a lot of conversations between senators, but I never talked about it with anyone,” boasted barber Elbert Link in 1981.

Like the Senate itself, the shop was slow to shed its exclusionary past. A separate beauty salon for female senators and male senators’ wives operated until 1998, when it merged with the barbershop. Today, Senate Hair Care Services’ list of options features a racially diverse array of models of both sexes, the result of a 2003 controversy stemming from complaints that its staff was ill-equipped to handle the hair of black clientele. “The world is changing, and the barber shop is going to have to change with it,” Robert Foster, a black committee staffer, told Roll Call.

The most enduring complaint about the barbershop is its expense. In the late 1970s, the free haircuts and shaving mugs were cut off and the appointment book was opened to the public. Yet for more than a decade, the salon has racked up annual deficits in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, only to be bailed out by taxpayers. In 2012, it was more than $400,000 in the red (0.0000001 percent of federal spending). Small-government types fume when they observe that the House barbershop was privatized in 1994—and charges $6 less for a trim.

Nevertheless, I was happy with my subsidized manicure. As I write this, it has been six whole days since I visited Senate Hair Care Services. And I can still see my face in my fingernails.