Mike Kane/San Antonio Express-News via ZUMAPress

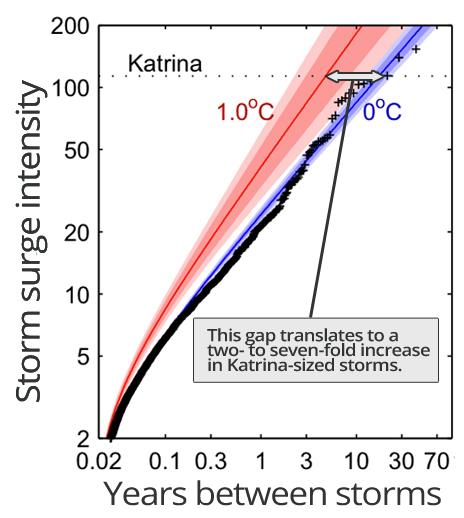

Batten down the hatches, East Coasters: A new study argues that for every one degree Celsius (1.8 degrees F) of global warming, the US Atlantic seaboard could see up to seven times as many Katrina-sized hurricanes.

That’s the conclusion of Aslak Grinsted, a climatologist at Copenhagen’s Niels Bohr Institute, who led an effort to match East Coast storm surge records from the last 90 years with global temperatures. His results, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that the strongest hurricanes are likely to become more commonplace with only half the level of warming currently projected by scientists.

“There is a sensitivity to warming, and it is surprisingly large,” Grinsted said.

The study compiled storm surge measurements from tide gauges at six locations on the East and Gulf Coasts, filtering out the effects of seasonal cycles, daily tides, and overall sea level rise to isolate the impact of storms. Next, these records were stacked against both global temperatures and a series of other climatic factors, like natural water temperature cycles and regional rainfall. The result? Global temperatures turned out to be one of the best predictors for hurricane activity. Using computer models, Grinsted found that a one-degree (C) rise in global temperatures could multiply extreme hurricane frequency by two to seven times.

When it comes to extreme weather, hurricanes are among the most costly events—and also among the least understood. Most of our understanding of the link between hurricanes and climate change traces to a research paper released in 2010 that argued that hurricanes worldwide could become up to eleven percent more intense by 2100; Grinsted’s research adds the wrinkle that the biggest storms, in addition to becoming bigger, are likely to happen more often. That is, in the US: Grinsted said exact projections would likely differ for other coastlines across the world.

There’s still a lot of work to be done on predicting hurricane activity in the face of climate change, said J. Marshall Shepherd, head of the University of Georgia’s atmospheric sciences program, who wasn’t an author on this paper but called it a “very important” addition to the underdeveloped body of scientific literature on this subject. A key step will be adding more exact sea surface temperature measurements from satellites into datasets like Grinsted’s, since hurricanes are as much a product of the ocean’s climate as they are the atmosphere’s.

“It is often lost on many that the ocean, like the atmosphere, is also warming,” he said. “It represents a vast reservoir of untapped heat that won’t be realized for many years.”