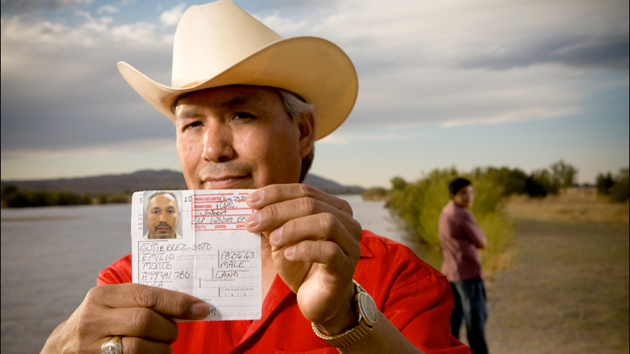

Former Mexican President Felipe Calderón <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/ciat/5242394248/sizes/m/">CIAT International Center for Tropical Agriculture</a>/Flickr

Former Mexican President Felipe Calderón, who led a controversial military crackdown on drug cartels, is moving to the United States to take an academic fellowship with Harvard University. But protesters, both Mexican and American, say that given Calderón’s political past, he shouldn’t be offered this prestigious position or even allowed to work here.

“It’s a total disgrace to the families of Mexican citizens who lost their lives because of the drug war,” says John Randolph, who worked for the US Border Patrol for 26 years before retiring, and has posted a petition on Change.org asking Harvard to rescind Calderón’s fellowship.

Randolph’s petition, which has received more than 6,700 signatures, cites evidence similar to that presented in a 2009 Mother Jones article on the drug war by investigative journalist Charles Bowden. In his story, Bowden details how after taking power in 2006, Calderón failed to protect persecuted journalists and used the Mexican Army (and over a billion dollars in American aid money) to fight the drug cartels, a strategy that has resulted in more than 60,000 deaths and the disappearance of thousands.

“I can’t help but think of the Mexican people who have tried to legitimately gain asylum in the United States because of the drug war—and have been turned down,” says Randolph. “How can Calderón waltz in and work for Harvard?”

Eduardo Cortés Rivadeneyra, who runs a construction business in Puebla, Mexico, has started a similar petition (in Spanish). He tells Mother Jones that he felt “insulted” when he heard the news of Calderón’s appointment at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “I assure you that thousands of Mexicans don’t want Calderón to teach in the US or anywhere else,” he says.

According to a statement by Harvard Kennedy School dean David Ellwood, “President Calderón is a distinguished alumnus of the Kennedy School and is known for his efforts in Mexico to improve the economy, expand and protect public health, address the drug problem, and engage with other world leaders around shared goals.” During Calderón’s fellowship, students will have the opportunity to ask him “difficult questions on important policy issues,” according to Ellwood’s statement. Harvard Kennedy School spokesperson Molly Lanzarotta points out that the inaugural fellowship, which is designed for retiring world leaders, is a one-year position, “not a faculty teaching appointment.”

Harvard isn’t the first university to try to get the former Mexican president onto its campus. In 2012, Calderón was in talks with the University of Texas at Austin. Once news got out that Calderón was meeting with the university president, students and other community members staged a protest on campus, disrupting a meeting of top Mexican government officials. Ultimately, Calderón never had any follow-up discussions with the university or job offers, according to Gary Susswein, a spokesman for the university. Susswein adds that the decision-making process took place “independent of any protests.”

Angelica Ortiz Garza, who doesn’t have any connection with the university but started an online petition against Calderón’s nomination at UT Austin, believes the protests “definitely had an impact on their decision.” But unlike UT Austin, she notes, Harvard is “far from the border” and Calderón’s time there as a student carries a lot of weight.

“So many tragedies occurred while he was in power, people are poorer, the country is in big debt, and there is a lot of corruption,” Garza says. “Unfortunately this has been always the case in Mexico, presidents usually leave the country to work or live in a better place.”