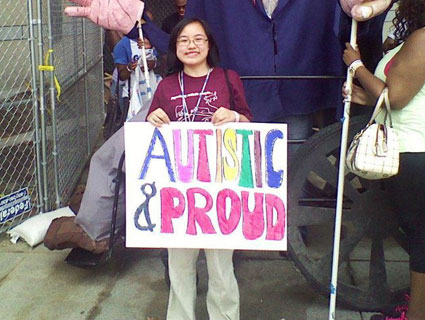

19-year-old Lydia Brown, an autistic undergraduate at Georgetown, says she fits the media stereotype of a mass shooter "perfectly."Courtesy of Lydia Brown

In the aftermath of the mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, journalists rushed to pathologize whatever drove Adam Lanza to mow down 20 children and six adults with a semi-automatic rifle. Perhaps, they implied, it was his alleged Asperger’s Syndrome, an Autism Spectrum Disorder characterized by difficulties in interpreting social cues and communicating emotion.

For example, sources speaking with the New York Times, described Lanza as an intelligent, friendless loner, with a “flat affect” who never showed any “emotions going through his head.” He was, said a doctor on Fox News’ Hannity, “out of touch with reality” and “didn’t have empathy.” Like other autistics, Lanza, said a psychologist on CNN, was “missing something in the brain.” (It’s worth noting neither of the networks’ “experts” specialize in neurological disorders, like autism.)

For people in the autism community, their response to the media’s portrayal of the gunman’s diagnosis was frustration—and anger. This again?

“We are a community that faces tremendous stigma and prejudice, and unfortunately when this happens, the mainstream media presents stereotypes and inaccurate information about autism and disability that only make that stigma and prejudice worse,” says Ari Ne’eman, who is the president of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network and himself autistic.

Although there’s no evidence suggesting autistic people are more violent than the general population—in fact, studies show the opposite may be true—this isn’t the first time journalists have made the specious connection between autism and heinous criminal acts. The Monday after the mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, MSNBC host Joe Scarborough speculated on-air that shooter James Holmes was “somewhere, I believe, on the autism scale” and “more often than not,” mass murderers are autistic.

Earlier this summer, the Daily Mail perpetuated two other common myths about autistic people when the UK paper described Anders Breivik, the Norwegian terrorist who fatally shot 69 people at a summer camp in July of 2011, as having a “rare, high-functioning form of Asperger’s that has left him incapable of empathy or real friendship.” While that might be true of Breivik, the notions that autistics are incapable of feeling empathy and avoid human companionship have been repeatedly debunked.

“We want to hunt for explanations. We want reasons for horrible things that happen,” says Steve Silberman, a Wired reporter who’s currently writing a book about autism and neurodiversity. “The problem is that people tend to go for these sort of pre-packaged, stereotypical explanations …and that’s one way we make people who commit these acts seem not like us…and somehow less than human.”

This shoddy reporting, particularly from influential and far-reaching news outlets, has real consequences in shaping the public’s perception of autism and other disabilities, Ne’eman explains.

“We’re like anyone else. We’re people who apply for jobs, look for places to live, apply to colleges. We’re generally looking to be included in society and when there is a myth out there that we’re people you have to be afraid of, that has a practical impact,” he says. “We talk to a lot of people, for example, who are discriminated against in the workplace after they disclose their diagnosis.”

Lydia Brown, an autistic 19-year-old sophomore at Georgetown University, worries that stereotypes about autistic people will affect her employment opportunities. Despite an impressive resume, Brown is admittedly socially awkward. In high school, after another student overheard her telling a joke about one of her novels, a school administrator called her into his office and accused her of plotting a school shooting.

“I’m actually pretty terrified,” Brown said when asked if she was concerned about the media’s depiction of mass murderers like Lanza. “Because I’m the kind of person who fits this profile perfectly.”

In the days following the Newtown shooting, Brown said her blog picked up traffic from more than a dozen different Google search terms linking autism and murder. The searches were all along the lines of “are autistic people more likely to kill”, “how many mass shooters were autistic,” and “are people with autism dangerous.”

“It’s really bothersome that we have to even be having this conversation,” says Shannon Des Roches Rosa, an editor for The Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism whose 12-year-old son, Leo, is autistic. “We don’t want to go out there and have to defend them as [not being] murderers or [ourselves as] parents of murderers. We should be talking about gun control, better mental health support. We should be joining everyone in mourning.”