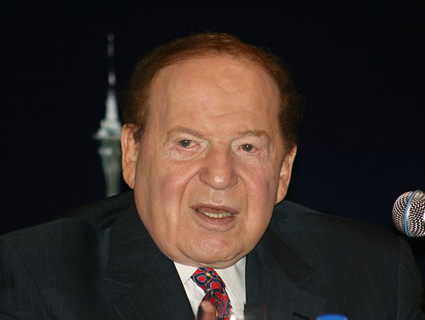

Sheldon Adelson, left, and George SorosColor China Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com; Lapresse/Daniele Montigiani/LaPresse/ZUMAPRESS.com

Can’t buy me gov.

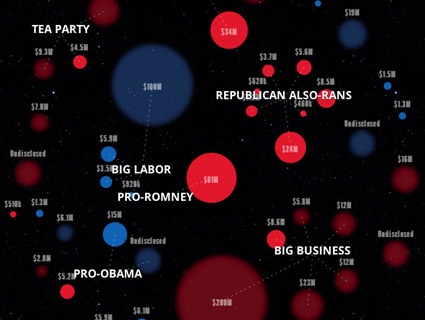

That line neatly sums up the dismal showing on Election Day for the fundraisers, super-PAC strategists, and big-dollar donors of the Republican Party. Outside groups spent north of $1 billion this campaign season—bankrolled mostly by a small cadre of wealthy contributors—and yet they and their funders, especially on the Republican side, were left with little to show for it when the sun rose Wednesday morning. The GOP’s flagship super-PAC, Karl Rove’s American Crossroads, had an abysmal 1 percent return on its $104 million investment. Megadonor Sheldon Adelson and his wife, Miriam, invested $57 million in 2012 races; only 42 percent of the candidates who received Adelson support won. Other big donors—say, Romney super-PAC backers—got nothing for their money.

Rove and his allies are bound to have a bunch of angry rich guys on their case. Which begs the question: Will the Republican Party’s biggest bankrollers stick by Rove, super-PACs, and politically charged nonprofits—or do they shut their wallets and move on?

Recent history suggests that the GOP’s megadonors might opt to sit out the political money wars in the 2014 campaign season. Think back to 2004, the last election in which wealthy bankrollers played starring roles. Then it was Democrats, not Republicans, giving seven- and eight-figure sums to influence the presidential race. Insurance executive Peter Lewis gave $23 million and Hollywood producer Steve Bing coughed up $14 million to independent Democratic groups such as America Coming Together (ACT) and the Media Fund. Liberal financier George Soros’ record-setting $24 million in donations spawned a thousand conservative conspiracy theories; Republicans claimed that Soros “had purchased the Democratic Party.”

What that money didn’t do was oust President George W. Bush. Despite early exit polls suggesting a John Kerry win, Bush overcame America Coming Together’s extensive get-out-the-vote effort and the Media Fund’s ads and won a second term. Bush’s win demoralized big Democratic donors. “They thought it was big waste of money because we didn’t win the White House,” recalls Ellen Malcolm, who cofounded ACT.

The 2004 election soured Soros, Lewis, Bing, and other Democratic donors on investing heavily in campaign-centric causes, Democratic fundraisers and insiders say. Soros shifted his giving away from pure politics, preferring to fund causes devoted to building up progressive infrastructure. (Soros did give $2.5 million to super-PACs in 2012, but that’s a tenth of his 2004 investment.) Neither Bing nor Lewis has come close to matching their 2004 donations. “They definitely cut back their funding significantly and that has remained the case,” Malcolm says.

The 2004 election soured Soros, Lewis, Bing, and other Democratic donors on investing heavily in campaign-centric causes, Democratic fundraisers and insiders say. Soros shifted his giving away from pure politics, preferring to fund causes devoted to building up progressive infrastructure. (Soros did give $2.5 million to super-PACs in 2012, but that’s a tenth of his 2004 investment.) Neither Bing nor Lewis has come close to matching their 2004 donations. “They definitely cut back their funding significantly and that has remained the case,” Malcolm says.

Republican megadonors could follow suit, giving less money to election-specific causes—or not donating at all. GOP funders have yet to publicly turn their backs on Rove and the super-PAC strategists who failed so spectacularly in 2012. But privately there’s “real anger” among donors and the grumbling has already begun, says one Republican strategist who knows the party’s donor landscape. “Publicly, they’ll say our investments were good this fall,” says the operative, who requested anonymity to avoid ruining relationships with donors. Behind closed doors, however, “I think a lot of people are gonna be asking: How was the money spent?”

This operative says the early reaction among some GOP donors was: “TV ads suck; ground game is what we need to look at.” These donors “are reconsidering what the future is like and what to emphasize.” Another Republican insider told the Huffington Post that the “billionaire donors I hear are livid. There is some holy hell to pay.”

Foster Friess, the retired mutual fund investor, told Politico this week he was “sort of burned out right now—just how much effort and resources I put into it.” Friess, no fan of negative advertising even before he joined the big-donors’ club, gave more than $2 million to the Red, White, and Blue super-PAC as a way of single-handedly keeping Rick Santorum competitive in the GOP presidential primary. Friess also chipped in hundreds of thousands more to super-PACs backing Romney and Senate candidates George Allen in Virginia and Connie Mack in Florida. All three candidates lost.

Donald Trump, who gave $100,000 to the Congressional Leadership Fund super-PAC, minced no words in the wake of Tuesday’s elections. He tweeted on Wednesday: “Congrats to @KarlRove on blowing $400 million this cycle. Every race @CrossroadsGPS ran ads in, the Republicans lost. What a waste of money.” (Numerous other big donors, including Adelson, did not respond to requests for comment about future giving.)

The Republican strategist predicts a shift among Republican and traditionally conservative donors away from pure politics and toward building a lasting get-out-the-vote infrastructure for future elections. “Just like we saw the food pyramid be dramatically flipped putting milk and proteins on top instead of grains, you’re gonna see a flip in conservative circles,” he says. “Instead of TV ads and mailers, it’s going to be voter outreach and microtargeting.”

From what he’s seen working with wealthy Democrats, Rob Stein, founder of the Democracy Alliance, a network of progressive donors, says it’s “entirely possible” that some big donors on the other side ditch Rove and take their millions elsewhere. But don’t think the GOP’s powerful super-PACs are fading into obscurity anytime soon. “I have a lot of faith in the abliity of Rove, [American Crossroads cofounder] Ed Gillespie, and Haley Barbour to say to their donors, ‘Slow down, guys, we’re political operatives and look what we built here,'” Stein says. “They gained a lot of knowledge, and it’ll come back and haunt us in 2014.”