Photo Illustration: <a href="http://preprod.motherjones.com/authors/dave-gilson">Dave Gilson</a>; <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=college+campus+girls+bench&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=85571599&src=30d981fe624f7591fe605aaa7d20a25d-1-4">Tyler Olson</a>/Shutterstock.

Last year, when Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Corbett suggested offsetting college tuition fees by leasing parts of state-owned college campuses to natural gas drillers, more than a few Pennsylvanians were left blinking and rubbing their eyes. But it was no idle threat: After quietly moving through the state Senate and House, this week the governor signed into law a bill that opens up 14 of the state’s public universities to fracking, oil drilling, and coal mining on campus.

For a system starved by budget cuts, it’s an appetizing deal: The Indigenous Mineral Resources Development Act mandates that 50 percent of all fees and royalties from the mineral leases will be retained by the university where those minerals are mined, 35 percent will be distributed across the state system, and another 15 percent will go towards subsidizing student tuition.

Of course, those benefits don’t take into account externalized costs.

Environmentalists and educators are concerned that fracking and other resource exploitation on campus could leave students directly exposed to harms like explosions, water contamination, and air pollution. They’re also worried oil and gas development would leave campuses ruined for future generations. It doesn’t help that Pennsylvania has a lousy regulation record, with a tally of violations that have increased more than fourfold since 2005. According to the PennEnvironment Research and Policy Center, Pennsylvania drilling companies racked up a total of 3,355 violations of environmental law between 2008 and 2011, 2,392 of which posed a direct threat to the environment and safety of communities. Meanwhile, in 2010, the state left 82,602 active wells go uninspected, more than all the active wells in New York and Ohio put together.

“Students need a place to learn and grow, but they’re being forced to jeopardize their health to get that education,” says Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of Delaware Riverkeeper, a local water quality watchdog. “This has been a big giveaway by the state of Pennsylvania to drilling interests, and it’s at the expense of students and the public.”

Still, that giveaway deal can look awfully sweet, especially when the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education has been struggling under Governor Corbett’s draconian budget cuts. In 2011, Corbett, who received $1.3 million from the oil and gas industry in his 2010 election, slashed funding for PASSHE’s 14 schools by 18 percent. Though he briefly floated the idea of cutting another 20 percent from the system in February, cuts remained at the previous year’s levels in the final draft of budget deliberations. That same budget also included a $1.7 billion tax break for Shell in order to coax a refinery into Western PA.

Professor Bob Myers, who runs the environmental studies program at Lock Haven University, one of the schools at the edge of the Marcellus, says he understands the school system’s economic concerns. Still, he’s horrified at the prospect that PASSHE might install rigs near students. “I’ve become extremely concerned, disturbed, and disgusted by the environmental consequences of fracking,” Myers says. “They’ve had explosions, tens of thousands of gallons of chemicals spilled. And we’re going to put this on campus?”

Pennsylvania isn’t alone, nor was it the first to come up with the idea of funding higher education with natural gas revenue. A couple of colleges in West Virginia have leased their land to fracking companies, and Ohio has a similar law to Pennsylvania’s. The University of Texas also makes money from natural gas well pads on its land, and even installed one 400 feet away from a daycare center at its Arlington campus. (The daycare center has now moved.)

While the new Pennsylvania law will apply to all 14 member universities within the State System of Higher Education, the six schools that sit on top of (or are adjacent to) Marcellus Shale are likely the most economically viable to frack. Below is a map of the Pennsylvania schools that are subject to the provisions of the act, the PA schools that sit on top of the coveted shale, and universities outside of Pennsylvania that are leasing or considering leasing natural gas acreage on their land.

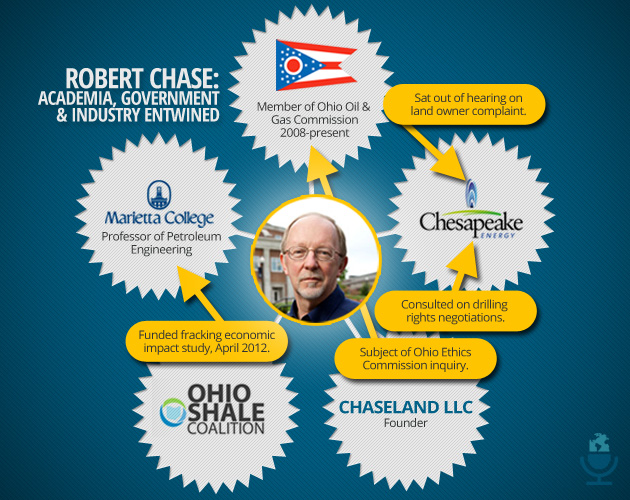

But natural gas is shaping more than just the physical landscape of public education. Penn State University, which is part of a separate state school system from PASSHE, has been dealing with a backlash of public criticism over oil and gas-funded fracking research. Last week, the Marcellus Shale Coalition, a fracking advocacy group, pulled a Penn State study it had paid nearly $150,000 to support after faculty members declined to participate. Earlier reports from that study, co-authored by former Penn State professor and paid industry researcher Tim Considine, were met with accusations of bias, similar to the infamous SUNY-Buffalo study produced by its industry-funded Shale Resources and Society Institute, and a University of Texas at Austin report that was actually authored by a millionaire drilling company board member.

It seems, however, that there might be one obstacle in the bum rush of the fossil fuel industry into state schools. Under Corbett’s Indigenous Mineral Resources Development Act, presidents of the state universities would have to provide written authorization to allow drilling on campus. This could potentially provide a critical window for student voices to petition their university heads.

Ryan Patrick Egan, a junior at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, one of the colleges on Marcellus Shale, and active member of the college’s environmental club, says that even with the tuition benefit, he still would see a decision to allow fracking on campus as one of purely short-term gain. His club has been hard at work trying to get the IUP president to sign onto the Presidents’ Climate Commitment, which would pledge a target date for the institution’s carbon neutrality. Drilling rigs near the quad also wouldn’t be a good look against the university’s recent efforts at promoting sustainability through LEED certified buildings. “If this bill is implemented to full strength it’ll negate the progress that’s been made and push us two steps back,” Egan says.

Evidence suggests that college presidents aren’t immune to the influence of oil and gas companies. IUP’s current president Mike Driscoll, assumed his role at the university after a vice chancellorship at the University of Anchorage Alaska, where one of his crowning achievements was nailing down UAA’s largest corporate gift in its history—a $15 million donation from ConocoPhillips for an arctic engineering endowment and the name of the college’s new science center.

Myers sees the future buyout of PASSHE campuses as a sad consequence of Pennsylvania’s long entanglement in resource exploitation and get-rich-quick schemes. “We gave [the fossil fuel industry] carte blanche to the state,” he says. “And it’s just because Pennsylvania needed the money.”