As a safety instructor looks on, a fisherman jumps into the water in Narragansett, Rhode Island, during a safety drill. Commercial fishing is the deadliest job in America. Jesse Costa/WBUR

“Get your panic out now!”

Veteran fisherman Fred Mattera stands atop a fishing trawler at the Point Judith Harbor in Narragansett, Rhode Island, seagulls squawking by and a fishy mist in the air, and instructs the seven mostly young, tattooed men standing before him to pull on life-safety immersion suits that cover them from foot to head, to zip up and plunge feet first into the water. Then two groups of fishermen interlock like centipedes and take turns paddling backward until they reach a life raft where, going smallest man first, they pull in one by one.

This is survival training, and the plunge-and-rescue dry run is meant to gird the fishermen for the real thing, which comes too often in an industry beset by a high death rate and fragile federal net of protection.

Commercial fishing is the deadliest vocation in the United States. Four years running, from 2007 to 2010, the Bureau of Labor Statistics ranked commercial fishing as the most dangerous occupation in the United States. From 2000 to 2010, the industry’s death rate was 31 times greater than the national workplace average.

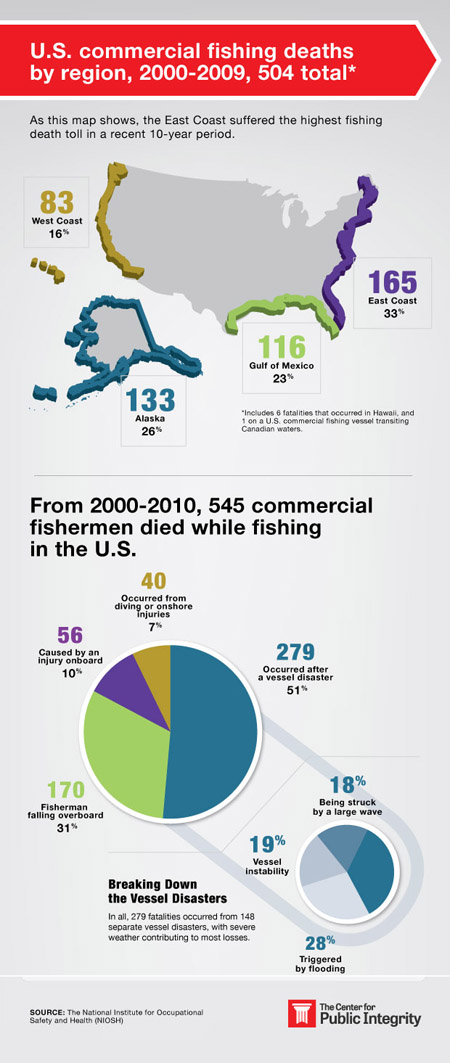

And no place, a recent National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health report reveals, is more deadly for commercial fishermen than the East Coast. From 2000 to 2009, the NIOSH report shows, 165 fishermen died from Florida to Maine. That’s more than Alaska—133 deaths—which had long been viewed as the most brutal place for commercial fishing but saw deaths dip amid a safety push. It’s a greater death toll than in the Gulf of Mexico, which suffered 116 deaths, or the West Coast, with 83.

The US Coast Guard has been granted only spotty powers to safeguard commercial fishing vessels, and the industry, steeped in a tradition of independence on the high seas, has long resisted government intrusion. Yet some longtime fishermen from Alaska to New England agree the federal safety net has left workers vulnerable.

“This has been an industry where there just hasn’t been a vigorous pursuit of safety at the federal level,” said former congressman James Oberstar, who held fishing safety hearings in 2007 as chairman of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

Advocates are trying to cast a new culture of safety. The immersion training in this seaside resort is one piece of a still-in-the works campaign—and, until full federal reform comes, a key ingredient to curbing losses at sea.

“Panic sets in when you don’t know what to expect,” said Mattera, who scrapped his dreams of going to law school 40 years ago when a roommate took him on a fishing boat, and who now runs a company leading safety seminars. “We’re taking that unknown out of it.”

In this tightly knit community, nearly everyone knows someone who died at sea.

“It’s like being a race car driver, one of those things you don’t want to talk about,” said lobster boat captain Norbert Stamps, who took part in the safety session with three crew members from his boat, Debbie Ann.

“We were all resistant in the beginning,” he said of the hands-on drills. “You now realize this isn’t fun and games. This is really serious stuff.”

Stamps began fishing at 13 and, after more than four decades on the water, said he takes his family to services for brethren lost at sea. “I’m preparing them for the fact that someday, something might happen,” he said. “You stay at sea long enough, everything happens.”

A decade ago, Mattera tried to rescue a friend’s 22-year-old son from a fishing hold 125 miles out to sea. The Rhode Island fisherman, Steven Follet, had collapsed, apparently after poisonous gases accumulated in the hold. Airlifted to a Cape Cod hospital, he died.

A decade ago, Mattera tried to rescue a friend’s 22-year-old son from a fishing hold 125 miles out to sea. The Rhode Island fisherman, Steven Follet, had collapsed, apparently after poisonous gases accumulated in the hold. Airlifted to a Cape Cod hospital, he died.

“Believe me, to this day it’s haunted me,” Mattera said. “Could I have gotten there five minutes sooner? All these things: My kid’s the same age as his. I will never forget coming in, going to see the family. In their eyes I was a hero. In my eyes I was a failure.

“In the end he’s not alive, and I swore to them, promised in his legacy we would change this culture of fishery.”

At his office overlooking the docks here, Mattera keeps a small picture of Follet on the wall near his desk. “It’s always in the back of your mind,” he said.

Inspection push snagged

For decades, safety advocates and government regulators have pushed for mandatory inspections of the often decades-old boats that take to deep water to bring back scallops, fish, squid, and lobster.

And for decades, Congress has stood still. Despite the strikingly high death rate among the men and women who live by the boat, the federal government has never required inspections of commercial fishing boats. The Coast Guard performs voluntary exams of safety equipment, and Congress recently acted to make those dockside reviews mandatory. But the law has yet to mandate detailed inspections of the vessels themselves.

“Fishing vessels are uninspected, so the Coast Guard doesn’t have jurisdiction to go on and look at the condition of the vessel. There’s no standards that a fishing vessel has to be built to or maintained to. That’s much different than a ferry or cargo ship,” said Jennifer Lincoln, a NIOSH epidemiologist based in Alaska who leads the agency’s Commercial Fishing Safety Research and Design Program.

“Every time there’s a vessel loss with high numbers of lives lost and the Coast Guard has done an investigation, one of the recommendations that always comes back is that these vessels should be inspected,” Lincoln said. “There’s industry push back: ‘That would be an expensive thing to do.'”

Pushing for sweeping safety changes, she said, is “like planting a tree.” The government can press for one change, and hope it sprouts into another. NIOSH can suggest reform, but has no law-writing power. That rests with Congress.

The National Transportation Safety Board has argued for vessel inspections and, in 2010, held a forum on fishing safety. “Fishermen tolerate long absences from home, inhospitable environments, and workplaces that are teeming with heavy, dangerous equipment while constantly in motion,” board member Robert L. Sumwalt III said at the hearing. “For some, the price paid is even higher: hypothermia, loss of limbs, and even death.”

From 2000 to 2010, 545 commercial fishermen died in the US, reported NIOSH, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than half of these deaths occurred after a vessel disaster, with boats sometimes swallowed by the sea. Another 30 percent involved fishermen falling overboard. Other deaths came from accidents on board, or while crew were diving or injured on shore.

Atlantic scallop fishermen suffered some of the highest death tolls, with a fatality rate more than 100 times the national average from 2000 to 2009, and some of the industry’s most notable disasters.

In December 2004, vast swells rolled the New Bedford, Massachusetts, scalloping boat Northern Edge on its side, plunging the crew of six into frigid waters 45 miles off Nantucket. One man survived, making the Northern Edge New England’s deadliest fishing tragedy since the sinking of Gloucester, Massachusetts’s, Andrea Gail in 1991, a case that inspired The Perfect Storm book and movie.

“I often wonder what is the true price of a pound of scallops,” fisherman Christopher Gaudiello said at the funeral for Northern Edge victims.

Mattera said the work can be brutal. “If you went scalloping for 10 days and stood in that box for 18 hours a day, day after day after day, you would not believe how fatigued you are,” Mattera said. “You cannot compare it to anything. Shuck and shuck and shuck, you would not believe the monotony. You are in constant pain…You are bringing a steel cage swinging in the seas. Man, that stuff hits you, you are a dead man or you are breaking hands, you are cracking skulls.”

A scalloper at work in New Bedford, Mass. Jesse Costa/WBURThere’s a human cost to the industry push back and congressional inaction, experts say.

A scalloper at work in New Bedford, Mass. Jesse Costa/WBURThere’s a human cost to the industry push back and congressional inaction, experts say.

Richard Hiscock, a longtime marine safety advocate from Vermont who worked as a US House staffer in helping to write safety laws, said government is too often “reactive to casualties.”

Marine safety laws on the books, he said, “have been what I described as the little Dutch boy going around putting his finger in the dike,” Hiscock said. “Every time there’s a major casualty there will be a lot of hubbub and there will be an investigation to see what we can do to improve the existing statutes and plug a loophole.

“And they’ve been doing this since 1838.”

Hiscock draws a contrast between the Federal Aviation Administration, which has broad power to ensure airplanes fly safely, and the Coast Guard. “Congress has given the Coast Guard little bits and pieces of authority, not the broad authority,” he said.

The Coast Guard’s website includes a Hiscock report, “The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities,” that details failed reform attempts dating years. In 1999, a Coast Guard task force issued “Living to Fish, Dying to Fish,“ a report citing the industry’s high casualty rate and lack of deep reform.

“Despite long-standing recognition of the serious hazards of commercial fishing, a long succession of proposed laws were not enacted,” the report concludes. “Many fishermen accept that fishing is dangerous, and lives are often lost. Many of those harvesting the bounty of our ocean frontier staunchly defend the independent nature of their profession, and vehemently oppose outside interference.”

Indeed, many fishermen have fiercely opposed government regulations—challenging, for instance, fish catch quotas some say hasten dangers at sea.

Reform’s Piecemeal Rollout

Strides have come, but slowly.

In 1988, Congress passed the Commercial Fishing Industry Vessel Safety Act, requiring fishing boats to carry survival craft, personal flotation devices and other safety equipment on board.

The regulations went into effect in 1991. A year later, the Coast Guard sought authority to inspect fishing boats. Approval never came.

“Whether the industry was lobbying enough or Congress didn’t see the need for it, we just weren’t given the authority,” said Jack Kemerer, division chief of the US Coast Guard’s Fishing Vessels Division.

Kemerer said the 1988 law and subsequent tweaks have helped drop death tolls from even higher numbers in the 1980s. “There have been improvements based on the law and safety programs and safety initiatives,” he said.

“But,” he added, “fishing still remains the most hazardous occupation in the country.”

In 2007, the House Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation held hearings, citing a string of tragedies from Alaska to Maine that had taken 22 lives in recent months.

A core of veteran fishermen, their spouses and safety advocates told the panel how they had lost friends to the seas.

“If we had regulated airline safety the same way we have regulated fishing vessel safety, all passengers on an aircraft would be issued a parachute and be trained in how to use it,” said Jerry Dzugan, executive director of the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association. “The fishing vessel safety act focuses on survivability after a vessel loss. By anyone’s definition, this is a reactive, rather than a proactive approach to casualties.”

Maine lobster fisherman Robert Baines described finding two teenage boys—aspiring fishermen—drowned in the cold April waters after their boat, inadequate for the weather conditions, capsized. One boy’s body washed ashore; Baines found the other in the water. “I will never forget that unnecessary tragedy,” he said. When the 1988 law passed, he said, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association opposed safety requirements for state registered vessels. “Times have changed,” said Baines, chair of Maine’s Commercial Fishing Safety Council.

Oberstar, then the transportation committee chair, concluded that the government needed a “much more vigorous program” and national standards to safeguard the industry.

He too draws a contrast between the FAA’s powers and those handed the Coast Guard. “Safety in aviation shall be maintained at the highest possible level, not the level industry can afford,” Oberstar said, and flights can be grounded with a mechanic’s signature. “That’s the kind of standard we need for Coast Guard inspectors.”

That standard has not come, but another reform swell passed with the US Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010. Congress approved an amendment requiring the Coast Guard to examine safety equipment on commercial fishing vessels every two years.

Now, fishermen can seek voluntary examinations of their safety equipment. If they pass, they get a sticker. If they fail the so-called “No Fault Exam,” no violation is issued. Captains of failed boats do risk citation if they take to the seas and happen to be boarded by the Coast Guard. The 2007 congressional hearing, however, revealed that less than 10 percent of the commercial fishing fleet took advantage of the voluntary program.

But even that voluntary review couldn’t ensure fishermen knew how to use the equipment. “That’s like taking your car in to go in for a safety sticker, and then you get into it and you don’t buckle up and you drive down the highway,” said Rodney Avila, a New England fisherman and safety advocate.

Under the new rules, which could go into effect later this year or next, the Coast Guard will check to ensure safety equipment is up to date and boats have proper life preservers, survival suits, life rafts, flares, alarms and documentation. The Coast Guard has not yet decided what consequences would follow a failed exam—but one possibility is that the boat would not be allowed to sail.

The rules also call for enhanced training of fishermen and lay the groundwork for safety compliance programs for older or substantially changed vessels.

Still, the pending mandatory dockside exams do not call for Coast Guard inspections of the vessels themselves. That would entail a “cradle-to-grave program” in which the Coast Guard issues a certificate of inspection, re-inspects the boat every year and conducts an out of water inspection every five years.

There’s a big difference, the Coast Guard’s Kemerer said, between an exam and a fuller inspection. “Safety would certainly be improved,” he said.

To some, having equipment exams but not the vessel inspections is like checking a car’s seat belts and air bags, but never getting around to the engine and frame.

Who is to blame?

“That’s the $64,000 question,” Hiscock said. “It’s a shared responsibility. Congress has never had the courage to do it, and the industry has never pushed for it.”

Kemerer said the exam could be a step toward more extensive inspections one day. The stakes, he said, warrant it. “When a serious emergency develops…the fishermen, if they haven’t practiced getting into their life suit or how to deploy a life raft, they are facing death,” he said. “Sometimes you only have a matter of minutes.”

Still, a question begs: If inspections came, who would pay for them in an industry with approximately 20,000 federally documented fishing boats and some 50,000 state registered vessels?

“We’re talking about hundreds of inspectors that would be needed, but right now with the budget climate the way it is, there’s no way we could get the number of inspectors,” said Kemerer. “It would be great to have it. The challenge would be: How do we accomplish it?”

Hiscock, the former House official, questions just how hard the Coast Guard has pushed for a full vessel inspection program. “They’re not up there lobbying for inspections constantly,” he said.

Deaths at Sea

In a stretch of New England where seafood is king, tragedies continue.

Up and down the East Coast, fishermen set out to make a living, but then lose their lives. Some were unprepared for the catastrophe confronting them, government records show.

- In March 2009, the Lady Mary—a 76-foot fishing vessel—sank in 210 feet of water 65 miles off the New Jersey coast, killing six crew members. The NTSB said flooding, triggered by a hatch mistakenly left open during rough weather, likely sank the ship.

- In January 2009, the Patriot sank 14 miles east of Gloucester, drowning its two crew members. “The Coast Guard attributes the vessel’s loss to a rapid event, most likely a capsizing, that did not allow the crew time to respond or access live saving gear,” a Coast Guard report found.

“Everyone thinks it’s never going to happen to them, that’s the problem,” said Avila, who served on the New England Fishery Management Council. “A lot of fishermen have never set off flares…A lot of fishermen have been fishing for 40 years and they may not have inflated a life raft. Most people don’t read [the instructions] until you need it.

“And when you need it, you have a minute or two until the boat sinks.”

Avila is among the reform advocates in New Bedford, a city of 95,000 some 60 miles south of Boston founded by whalers. Fishing remains the city’s lifeblood and, occasionally, a cause of mourning.

A string of New Bedford fishing boats sank in frigid, rough waters beginning in 2004.

When the Northern Edge went down that winter, the sole survivor was a crew member who had taken safety training in Portugal. That survivor, Pedro Furtado, later filed a lawsuit and contended the boat operator improperly stored life safety suits in an engine room—where the crew couldn’t reach them in emergency.

In January 2007, New Bedford’s 75-foot Lady of Grace—battered by 40-knot gales, and taking on ice—was missing at sea as it staggered to escape the weighty chill and return safely to harbor.

On January 26, five days after Lady of Grace set out to lure fish and scallops, the Coast Guard found the vessel submerged in 56 feet of water at the bottom of Nantucket Sound. Like so many New England fishing boats, Lady of Grace was workmanlike, not sleek, and aged—built 29 years earlier, its blue façade dotted with black marks.

Divers recovered the bodies of the captain, a fisherman for 25 years, and another crew member, in the business for 27 years. The bodies of the other two men did not surface. Heavy ice literally sank the boat, the Coast Guard concluded, drowning the men before they could reach port. Once more, the Catholic Church held solemn funerals, and the close-knit Portuguese community prayed for families left fatherless.

Avila knew everyone on that boat.

“I lost a lot of my friends that year, and it wasn’t a good feeling,” he said. “I was already into safety a little bit before that happened but that just confirmed it. I just dedicated myself to the safety program.”

A fisherman for more than five decades, Avila said he felt invulnerable to tragedy. After all, he reasoned, he always spent money for safety equipment.

“Even though I had all the best equipment, I didn’t know how to use it,” he told the NTSB forum in 2010. “And right then and there, a light bulb went off and I started looking at all my fellow fishermen in my port one by one, who had started fishing with me, and they were in the same boat—different vessels, but same boat. They had the best equipment, but they didn’t have the knowledge to use it.”

Avila got a wakeup call when he flew to Alaska for safety training himself. “I thought I knew everything there was to know about it until I sat in his class. And then I scratched my head the first, maybe the second day and I said boy, I really know nothing about this,” he told the NTSB.

Now, like his friend Mattera, he leads drills that prepare fishermen for the worst—and get them intimately acquainted with equipment that could save their lives. The best safety equipment is useless, he learned, unless you know how to operate it: How to quickly zip into a life suit. How to inflate a life raft, send a mayday call, plug a gaping leak on a boat taking on water. With help miles away and unforgiving waves pounding, fishermen have scant moments to act.

“The problem with a boat, when something happens or breaks, you are out in the middle of the ocean,” said Mattera, the long-time fisherman from Rhode Island. “It’s not like you are out at the curb and can call AAA.”

Using the life-saving gear can mean the difference between death and survival.

Lincoln, the NIOSH official from Alaska, said getting into an immersion suit increases odds of survival by 7 percent. Getting into a life raft, she said, increases survival chances by 15 percent.

In Alaska, a safety campaign supported by industry helped lower the death totals. There, NIOSH studied the industry’s high fatality rate and focused on the sectors, such as the crab fishery, with the highest numbers. “NIOSH would look at the fishing data for the entire state, and we identified a hazardous fishery and then we worked with the Coast Guard and crab fishermen,” Lincoln explained. “What can we do to prevent these fatalities from happening?”

NIOSH intends to use the same targeted approach in the East Coast, Gulf Coast and West Coast, using its region-by-region breakdown as a guide. “What’s that one or two things we need to focus on to intervene so that fatalities start decreasing?” Lincoln asked.

Lasting reform, she said, requires industry buy in and a focused, not “one-size-fits-all mentality.” Having fishermen help lead safety drills is one piece of the puzzle. “If the training can be led by the fishermen, then they already have credibility by the people they are trying to train,” Lincoln said.

The potential for tragedy is compounded by the economics of an industry that experiences steep price swings—and feels the domino effect of a still-shaky economy. Looking to save money, some captains set out with fewer hands on deck, leading to fatigue during the long days on the water. They stay out in dangerous weather to lure the extra fish that will reel in a bigger bounty. And, they put off housekeeping.

“When you have economic hardship, a lot of times the first thing you neglect is the safety equipment,” Mattera said.

“Stretching it out,” he calls it. “It’s like having a home and knowing you should paint your home every 10 years. And when 10 years comes it costs you $10,000 to paint it and you already have a second mortgage. You either do it yourself, which ends up being half-ass, or you wait.”

Mattera said he and Avila had been complacent before tragedy spurred them to act. “Now we’re like pains in the asses to everybody because we’re so committed to this,” said Mattera, who until recently owned an 84-foot trawler, Travis & Natalie, named after his now-adult children.

After a boat goes down, Avila said, everyone starts pointing fingers. At the boat owner, the government, the regulations. His goal is to shift from the blame game to a culture where fishermen are prepared for chaos at sea. “If you go out fishing and you’re not prepared for any disaster, that’s like you going into a gunfight with a pea shooter.”

In Rhode Island this month, Mattera played the role of man overboard in another drill. Using their might and a yellow lifeline, two men pulled him back aboard. “Like a swordfish,” Mattera said, “235 pounds.”

One of the rescuers, Mike Gallagher, recalled finding a friend dead on a boat in 2002. The man, fishing alone, had not returned at day’s end, and Gallagher searched for him the next morning. Trapped by equipment onboard, the fisherman was dead from head trauma.

“I used to fish alone back then,” said Gallagher. “I never went alone after that.”

This story was produced in collaboration with NPR and WBUR in Boston. The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit, independent investigative news outlets, for more of their stories go to www.publicintegrity.org.