Illustrations by Barry BlittOn March 21, 2005, a sandy-haired 43-year-old attorney named Mark “Thor” Hearne took a seat under the Greek Revival dome of the Ohio Statehouse to testify before the House Administration Committee. The committee was holding a field hearing on the subject of voter fraud, a hot topic in Congress—and in Ohio, where George W. Bush had eked out a narrow, hotly contested victory over John Kerry the year before.

Illustrations by Barry BlittOn March 21, 2005, a sandy-haired 43-year-old attorney named Mark “Thor” Hearne took a seat under the Greek Revival dome of the Ohio Statehouse to testify before the House Administration Committee. The committee was holding a field hearing on the subject of voter fraud, a hot topic in Congress—and in Ohio, where George W. Bush had eked out a narrow, hotly contested victory over John Kerry the year before.

Hearne introduced himself as counsel for the American Center for Voting Rights. The Buckeye State, he said, had suffered from “massive” registration fraud during the presidential election. Liberal groups like ACORN and the AFL-CIO were implicated in illegal voter registration schemes. An NAACP operative had paid for fake registrations in crack. Then, after enrolling thousands of phony voters, these same groups had flooded the courts with lawsuits designed to create bedlam on Election Day and prevent fraudulent votes from being discovered. To back up his story, Hearne submitted a 31-page report, signed by more than a dozen Ohio attorneys.

It was a startlingly lurid picture—and the latest chapter in a long-simmering feud between Republicans, who claim that fraud is rampant in US elections, and Democrats, who say such charges are merely an excuse to suppress the vote. Still, there was something different about this episode. It wasn’t just a one-off bit of bluster during a bitter recount battle. That would have been politics as usual. Instead, it marked a dramatic widening of the war. This was, after all, a congressional hearing, and Hearne represented an organization dedicated to pushing Republican claims of voter fraud not just during post-election court fights, but everywhere and all the time.

So two questions lingered after Hearne had finished his dramatic testimony. Who exactly was Thor Hearne? And what was the American Center for Voting Rights, a group no one had heard of before that day? Therein hangs a tale, one that starts on a nail-biter of an election night in a nearly forgotten battleground—St. Louis, Missouri.

On election day 2000, as officials in Florida wrestled with butterfly ballots and hanging chads, Thor Hearne—then the Missouri counsel for the Bush-Cheney campaign—faced a crisis. It had been a frantic day marked by long lines, improper purging of names from voter lists, and hundreds of voters turned away from the polls. As the problems in the overwhelmingly Democratic city mounted, the Gore campaign went to court to ask that the polls stay open three more hours. A judge granted the request, but Hearne appealed, and in short order, the decision was overturned.

Republicans were apoplectic over the Democrats’ maneuver. At stake were not only Missouri’s Electoral College votes, but also the fate of GOP Sen. John Ashcroft, who was locked in a tough reelection battle against a popular longtime rival, Democratic Gov. Mel Carnahan. Carnahan had died in a plane crash a few weeks before the election, but his widow, Jean, was set to serve in his stead. In the end, even as Bush carried the state, Ashcroft lost to a dead man.

Missouri’s senior senator, Kit Bond, fumed that Democrats had conducted “a criminal enterprise” designed to fraudulently register voters during the campaign and then create chaos on Election Day to cover it up. Republican losses, Bond told reporters, were due in part to dogs and dead people voting. Ritzy Meckler, a springer spaniel whom some jokester had registered to vote by mail, became a cause célèbre. A few months later, Missouri’s Republican secretary of state, Matt Blunt, released a report concluding that St. Louis Democrats had mounted “an organized and successful effort to generate improper votes in large numbers.”

It turned out there was nothing to these charges—no evidence ever surfaced of intentional fraud, only of confusion and bad management. But it didn’t matter. Hearne, Ashcroft, and Bond were now obsessed with voter fraud, and with Bush in the White House they had the power to do something about it.

Ashcroft went first. Having been appointed Bush’s attorney general, he quickly rolled out a new program to train US Attorneys and others to recognize and prosecute voter fraud. He also announced that he would designate special officers throughout the country to receive Election Day complaints about voter fraud and voter intimidation. “Election crimes are a high law enforcement priority of the Department,” his office announced. (Just how high a priority would become apparent a few years later.)

Then it was Bond’s turn. Shortly after Florida’s shoddy procedures became a national sensation in 2000, Congress began work on legislation to clean up the voting system. For the most part this was a bipartisan effort; both Democrats and Republicans had been appalled by the hanging-chad spectacle. The Help America Vote Act (HAVA) passed by huge majorities in October 2002 and was signed a few days later by President Bush.

But along the way, Bond made sure that the act was also a vehicle for his voter fraud crusade. Bond regaled reporters and senators with his tales of brazen abuses, often invoking Ritzy Meckler (who, it should be noted, never cast a ballot). The only way to fix these problems, he said, was to make sure each voter had to show ID at the polling place.

In the end, HAVA’s identification requirement was a modest one. It applied only to first-time voters in federal elections who, like Ritzy, had registered by mail, and it directed states to accept a wide variety of ID types. But even so, it was a historic first. Suddenly, voter fraud—real or otherwise—was in the national spotlight.

Republicans kept up the drumbeat of complaints for two years. As the 2004 election approached, the pace picked up. John Ashcroft launched new fraud investigations in swing states. Karl Rove, who earlier in his career had turned a razor-thin loss in an Alabama judicial race into a razor-thin victory by insisting that his client had been robbed—and eventually getting the Supreme Court to agree—went on Sean Hannity’s show to warn that “there has been a lot of voter registration fraud” in battleground states. Conservative journalist John Fund published Stealing Elections, a book claiming that shady vote-buying schemes by Democrats had left America’s elections resembling those of “an emerging Third World country.” Right-wing blogs trumpeted the case of Mac Stuart, a former ACORN employee who claimed he had been fired for refusing to go along with illegal voter registration activities in Florida.

And Thor Hearne? Well, his good work in Missouri had not gone unnoticed. He was now serving as national counsel for the Bush-Cheney reelection campaign.

But if Republicans spent the 2004 election season feverishly warning that Democrats were scheming to steal the White House, it was nothing compared to the furor among Democrats after the election. The early exit polls on Election Day had suggested that John Kerry was leading in virtually every key state, including the crucial battleground of Ohio. Yet by the time all the actual votes were counted, Kerry’s anticipated victory turned into a narrow loss—by a mere 120,000-vote margin in Ohio—and Bush secured a second term.

Outrage boiled over immediately, and not just around muttered conspiracy theories that Republicans might have rigged Ohio’s Diebold voting machines. Balloting problems were so widespread in 2004 that when the Democratic staff of the House Judiciary Committee wrote a report titled “What Went Wrong in Ohio,” the executive summary alone was three pages long. The bill of particulars was damning: Misallocation of voting machines led to long lines in Democratic precincts; Republicans knocked minority voters off the rolls with “caging” tactics (sending letters to voters’ listed addresses and purging those whose mail was returned); some 93,000 ballots were declared spoiled and left uncounted. The report blamed one man above all for these problems: Ohio’s Republican secretary of state, Kenneth Blackwell, who was also a state co-chair for the Bush-Cheney campaign. In one notorious move, Blackwell ordered county election boards to reject voter registration forms printed on paper of “less than 80 lb. text weight.” (This order, at least, was later rescinded.)

It was against this backdrop that Thor Hearne took the stand before the House Administration Committee in March 2005 to talk about the Ohio election—and shift the focus back to where Republicans felt it belonged, on deception by Democrats. And it was against that same backdrop that GOP legislatures across the nation began rolling out a brand new weapon in the voter fraud wars: the photo ID mandate.

In the past, states had accepted a variety of documents, such as utility bills and bank statements, to verify that a voter was who he said he was. But in ’05, Republicans in Indiana pushed through a law to change all that. It called, for the first time, for photo ID only, no exceptions.

Democrats opposed the bill, arguing that it was just a cynical effort to make it harder for people with no picture ID—often the young, the poor, and the nonwhite—to vote. The bill passed nonetheless, on a party-line vote. Then it was challenged in court, and three years later, in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, the US Supreme Court handed down a key decision upholding the photo ID requirement. Sure, wrote Justice John Paul Stevens for the majority, the law might have been motivated in part by Republican “partisan interest.” But so long as its goals were supported by “valid neutral justifications,” it was constitutional.

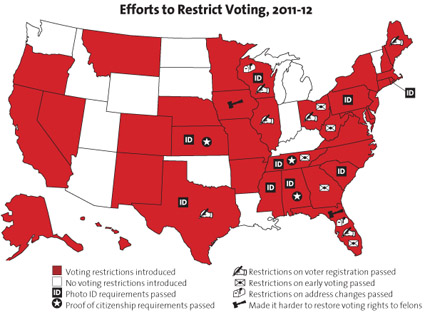

With that, the floodgates opened. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 16 states have now passed photo ID laws, and bills are pending in 11 more.

In retrospect, the campaign against voter fraud was long, patient, and strategic. Sen. Kit Bond got the ball rolling in 2002 when he made sure ID requirements were part of HAVA. In 2005, a commission on voting rights headed by former president Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker III gave a bipartisan blessing to photo ID rules. Thor Hearne spent the following two years barnstorming the country with dramatic tales of voter fraud. Meanwhile, the Justice Department and the Bush White House browbeat US Attorneys around the country to crack down on voter fraud, even firing a handful (including David Iglesias, then the US Attorney for New Mexico) who apparently weren’t zealous enough. And then, finally, the 2010 election brought new GOP majorities to 11 states—and with them a brand new wave of restrictive voting laws.

At this point, you may be wondering if there’s really anything wrong with all this. What’s the problem with cracking down on voter fraud? And why shouldn’t voters be required to show photo ID? If you need ID to cash a check or buy a six-pack, why not to vote?

The answer—surprising to many—is straightforward: Not everyone has, or can easily get, a photo ID. If you don’t drive, you don’t have a driver’s license. If you’re poor, you probably don’t have a credit card. And if you’re unbanked and don’t need ID to buy liquor, you probably don’t have much need for photo ID at all.

Once that sinks in, the electoral significance becomes obvious. In 2007, shortly before the Crawford decision was handed down, the Washington Institute for the Study of Ethnicity and Race released a study of Indiana voters showing that among whites, the middle-aged, and the middle class, about 90 percent possessed photo ID. Among blacks, the young, and the poor—all of whom vote for Democrats at high rates—the rate was about 80 percent. Overall, 91 percent of registered Republicans had some form of photo ID, compared to only 83 percent of registered Democrats.

Likewise, an NAACP report in 2011 concluded that the recent flood of new voter ID laws had a “disproportionate impact on minority, low-income, disabled, elderly, and young voters,” prompting an NAACP official to dub these laws “James Crow, Esquire.” Attorney General Eric Holder last year blocked South Carolina’s new photo ID law, noting that more than 80,000 minority voters in the state don’t have driver’s licenses.

Still, Republicans argue, anyone can obtain a photo ID with a modest amount of effort if they really want to vote. And isn’t this small amount of inconvenience worth it in order to crack down on fraud?

Sure—but first there needs to be some actual fraud to crack down on. And that turns out to be remarkably elusive.

That’s not to say that there’s none at all. In a country of 300 million you’ll find a bit of almost anything. But multiple studies taking different approaches have all come to the same conclusion: The rate of voter fraud in American elections is close to zero.

In her 2010 book, The Myth of Voter Fraud, Lorraine Minnite tracked down every single case brought by the Justice Department between 1996 and 2005 and found that the number of defendants had increased by roughly 1,000 percent under Ashcroft. But that only represents an increase from about six defendants per year to 60, and only a fraction of those were ever convicted of anything. A New York Times investigation in 2007 concluded that only 86 people had been convicted of voter fraud during the previous five years. Many of those appear to have simply made mistakes on registration forms or misunderstood eligibility rules, and more than 30 of the rest were penny-ante vote-buying schemes in local races for judge or sheriff. The investigation found virtually no evidence of any organized efforts to skew elections at the federal level.

Another set of studies has examined the claims of activist groups like Thor Hearne’s American Center for Voting Rights, which released a report in 2005 citing more than 100 cases involving nearly 300,000 allegedly fraudulent votes during the 2004 election cycle. The charges involved sensational-sounding allegations of double-voting, fraudulent addresses, and voting by felons and noncitizens. But in virtually every case they dissolved upon investigation. Some of them were just flatly false, and others were the result of clerical errors. Minnite painstakingly investigated each of the center’s charges individually and found only 185 votes that were even potentially fraudulent.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University has focused on voter fraud issues for years. In a 2007 report they concluded that “by any measure, voter fraud is extraordinarily rare.” In the Missouri election of 2000 that got Sen. Bond so worked up, the Center found a grand total of four cases of people voting twice, out of more than 2 million ballots cast. In the end, the verified fraud rate was 0.0003 percent.

One key detail: The best-publicized fraud cases involve either absentee ballots or voter registration fraud (for example, paid signature gatherers filling in “Mary Poppins” on the forms, a form of cheating that’s routinely caught by registrars already). But photo ID laws can’t stop that: They only affect people actually trying to impersonate someone else at the polling place. And there’s virtually no record, either now or in the past, of this happening on a large scale.

What’s more, a moment’s thought suggests that this is vanishingly unlikely to be a severe problem, since there are few individuals willing to risk a felony charge merely to cast one extra vote and few organizations willing or able to organize large-scale in-person fraud and keep it a secret. When Indiana’s photo ID law, designed to prevent precisely this kind of fraud, went to the Supreme Court, the state couldn’t document a single case of it happening. As the majority opinion in Crawford admits, “The record contains no evidence of any such fraud actually occurring in Indiana at any time in its history.”

This mountain of evidence suggests to most liberals that there’s another agenda at work: suppressing votes from Democratic-leaning populations. And Minnite’s research confirms a partisan tilt. Today’s voter ID laws are championed “almost exclusively by Republicans,” she told me, and, with only one exception, have been enacted only when Republicans have unified control in a state capitol.

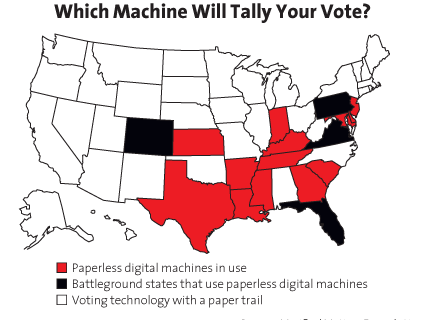

There’s more to voter suppression than just photo ID laws, of course (see our related charts), and the Brennan Center has identified a host of other tactics that have sprung up over the past few years. Some states have ended Election Day registration. Others have restricted early voting, which is more heavily used by minority voters. Laws requiring proof of citizenship have been proposed in a dozen states—a legislative push closely associated with the right-wing campaign against illegal immigration. Laws making it harder for students to vote have mushroomed. And last year Florida placed such stringent rules on voter registration drives that the League of Women Voters simply stopped conducting them.

None of this is a coincidence. In the same way that ACVR and Thor Hearne helped win the public-opinion war following the 2004 election, the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council picked up the ball after the 2008 election with model voter fraud measures that were prepackaged and ready to be enacted. With Republican majorities in place across the country, state lawmakers were eager to pass laws restricting voting rights. ALEC made it easy.

Yet as important as all these tactics are, photo ID laws remain the spearhead of the push to restrict voting rights. So it’s fair to wonder how much impact these laws have in real life.

The answer: It’s not entirely clear. The Brennan Center generated a lot of headlines for a recent report suggesting that upwards of 5 million voters could be affected just by laws passed in 2011. But a 2009 study published in Politics on the actual impact of voting law changes concluded that “voter-ID laws appear to have little to no main effects on turnout.”

Minnite, along with coauthor Robert Erikson, concluded much the same in a 2009 paper. They specifically investigated turnout among vulnerable groups in states with varying types of voter ID laws, and although they did find an impact, it was quite small and nowhere near statistically significant. “The moral is simple,” they concluded. “We should be wary of claims—from all sides of the controversy—regarding turnout effects from voter ID laws.”

As more states enact strict photo ID laws and the number of affected voters increases, it’s possible that empirical studies will more reliably show an effect. But it will likely remain fairly small, according to Rick Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California-Irvine. “Whether it’s really affecting a whole bunch of votes,” he told me, “I’m skeptical.”

The reason for this is pretty simple: Only about a tenth of the voting-age population lacks some form of photo ID, and that tenth includes a lot of demographic groups that already have low turnout in state and federal elections. That means a large number of them probably didn’t intend to vote in the first place, so the new laws have no real effect on them. Of the rest, many will go ahead and get the requisite form of ID even though it’s an extra effort. It’s only the remainder—say, one-tenth of the original tenth—who want to vote but end up being stopped because they can’t procure photo ID.

Still, in a close race, a modest effect can make a difference, and the cliff-hangers of 2000 and 2004 demonstrate that even presidential contests can hinge on tiny changes in turnout. If photo ID laws give them an advantage, however small, Republicans have an incentive to continue pushing for them.

Hasen offers another possible motivation: The voter wars, he suggests, have become a fundraising issue for both parties. Charges that the other side is stealing elections are incendiary, and promises to pass—or block—voter ID laws can be turned into demagogic appeals for money.

Those things may all be true. But even so, there’s one more layer to the voter fraud crusade.

If you’re the jaded sort, you might write off the whole thing as just another dreary example of cynical politicking. But what you can’t write off is the strong evidence that, as Hasen puts it, there are “underlying racial currents” in these laws.

Statistics tell part of this story: According to a survey by the Brennan Center, 8 percent of voting-age whites lack a photo ID, compared to 25 percent of blacks. Getting an ID card from the state usually requires you to produce a birth certificate, and Barbara Zia of the South Carolina League of Women Voters recently explained what this means in her state: “Many South Carolinians, especially citizens of color, were born at home and lack birth certificates, and so to obtain those birth certificates is a very costly endeavor and also an administrative nightmare.”

In St. Louis, where our story opened, Kit Bond’s outrage about dogs and dead people has a long pedigree. It is, a local official told the American Prospect‘s Art Levine, “code for black people.” This kind of racial dog whistling, which relentlessly paints ethnic minorities as corrupt and dishonest, is corrosive not just to our political discourse, but to democracy itself.

The scandal of the photo ID laws, then, isn’t so much that they give one party an advantage, or even that they affect minorities disproportionately. The scandal is that they knowingly target minorities. So even if the real-life effects of these laws are small, they’re impairing civil rights that African Americans and others have spent decades fighting, and sometimes dying, for. This in turn means that something most of us thought was finally taboo—active suppression of minority votes—isn’t really taboo after all. As Eric Holder put it in a speech earlier this year, there are those who fear that “some of the achievements that defined the civil rights movement now hang in the balance.”

Electoral politics has always been a dirty game, but in recent decades most of us felt that there was, at least, a consensus that systematic, national-level efforts to discourage minority voting were at last beyond the pale. But maybe we were just kidding ourselves.