Pete Marovich/ZUMA Press

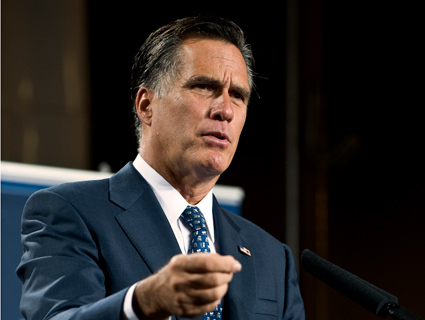

Mitt Romney has a particular effect on voters of the opposite sex—and it’s not a good one. During the heated final days of the GOP primary, female Republicans in many states favored Rick Santorum. Romney’s dismal luck with the ladies was more apparent in April, when, according to a Washington Post poll, he was trailing President Barack Obama among women voters by 19 percentage points. Romney’s female appeal hasn’t improved much in the past month. An NBC/Wall Street Journal poll released this week still puts him 15 points behind Obama.

His numbers are particularly dismal among single gals. While Romney leads Obama among married women by about 9 points, Obama blows him away among single women by 36 points. This matters: There are 55 million single women in the United States. If they got motivated, they are a big enough block to swing the election.

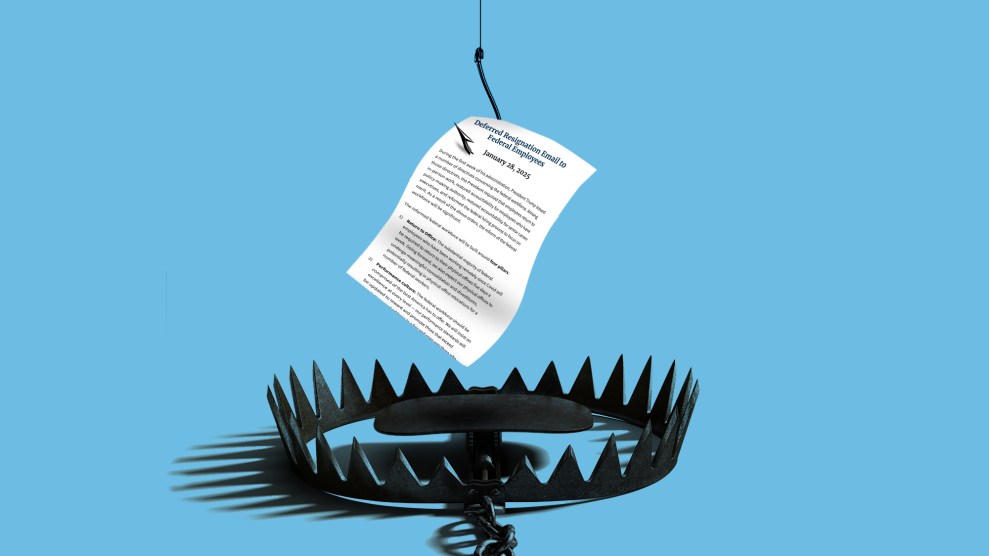

The Romney campaign has responded to the candidate’s female voter problem by deploying Ann Romney and putting the candidate on the stump with high-profile Republican women including Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.), Sen. Kelly Ayotte (R-N.H.), and South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley. It has also been prominently touting his recent endorsement by Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-Texas), who proclaimed Romney “the better choice for women.” He’s been peppering his stump speeches with stories of women he’s met on the campaign trail (people like “Woman Whose Husband Took an Upholstery Class,” as the AP dubbed her, because the Romney campaign has failed to actually identify any of these women). And recently the Romney campaign tried to take Barack Obama down a peg with women by insisting (falsely) that the majority of jobs lost during the recession were lost by women.

Republicans writ large have had problems with female voters for two decades: George H.W. Bush won the female vote in 1988 and lost it (and the election) in 1992. Bob Dole lost women voters by 16 points in 1996. And George W. Bush lost by 11 points in 2000 and 3 points in 2004. But Romney’s problem with women seems to go deeper than that of the average Republican candidate. Consider this: Romney has never netted a majority of women voters during any of his political races, even when he won.

In 2002, Romney won the governorship in Massachusetts largely by winning over men, who voted for him by 13 points over the Democrat. Romney lost the women’s vote by 4 points. The gender gap that year was the largest in that state since 1990, when William Weld became Massachusetts’ first GOP governor since 1975—largely thanks to the support of women voters. In 1994, when Romney ran for the Senate against incumbent Sen. Ted Kennedy, female voters picked Kennedy over Romney by 24 points.

There were unique factors in all of these races. Kennedy, a pro-choice and equal rights champion, was a legend in a Democratic state; Romney ran against a woman in the 2002 governor’s race. But in 2008, he lost the women’s vote in the GOP primary to Sen. John McCain (who then lost women voters to Obama by 13 points).

Romney’s performance in the GOP primary this year suggests that his gender deficit is an enduring one. Not only did Romney lose the women’s vote in many states to the ultra-conservative Santorum, but Newt Gingrich bested him among women in South Carolina—and that was after Gingrich’s second wife dropped the bombshell that her former husband had once asked her to have an “open marriage.”

Parsing just what it is that women don’t like about the presumptive GOP nominee isn’t easy because Romney, as you may have heard, is a bit of a social clunker. (Remember the “Who let the dogs out?” incident?) He strikes people in all walks of life as kind of awkward. But judging from the polls, men seem willing to overlook his goofy sense of humor, the fake butt-pinching episode, and the odd social interactions. Many women, though, seem to experience a dislike that can’t be explained solely by his (current) policy positions, which aren’t much different from those of other Republicans.

The clues to Romney’s women problem may lie in his personal history. His mother, a former Hollywood starlet, ran for the Senate herself. He also has two sisters; one of them, Jane, is an actress and a Democrat who has been called the “Billy Carter” of the family.) But at 12 and 9 years older than Romney, his sisters weren’t around the house to influence him in adolescence in a way they might have if they were closer in age. For the most part, his life has been characterized by his involvement in a string of virtually all-male or heavily male-dominated institutions. “Of most of the environments that he’s electively joined, women are, if not structurally excluded from leadership, they are historically excluded,” observes Joanna Brooks, a senior correspondent at Religion Dispatches and a Mormon feminist who’s been studying Romney for years.

Romney’s professional life was spent in the sausage fest of high finance and politics. That’s true of lots of men, especially rich ones who enter politics. But Romney is also steeped in a religious culture in which gender roles historically have been rigidly segregated and in which men and women operate in distinctly different spheres. His role in the male-dominated Mormon church has gone far beyond spending some time in the pews every Sunday. Romney was groomed from an early age to assume responsibility as a leader in the LDS church.

Within the Mormon church, laymen (and only men) are vested with considerable power, unlike, say, the Catholic Church, which is also male dominated but which has professional clergy. Male lay members serve as the Mormon church’s spiritual leaders. In that role, men like Romney are charged with counseling the faithful and laying down church law within their flocks, a job that has traditionally included trying to enforce the church’s strict vision of gender roles.

Brooks notes that it’s not unusual among Mormon men of his generation to have difficulties relating to women as equals in the professional world. She explains that they came of age at a time when the church openly opposed the women’s movement, which presented a significant challenge to a church whose theological and cultural logic is organized around strongly defined gender roles. As a result, she says, Mormon men of that era sometimes seem to have the sense that “there is no proper way to engage with women as adult equals.”

After attending an all-boys prep school in Michigan and then spending a year at Stanford, Romney, like most Mormon men, spent almost three years cloistered with other young men as a missionary. He was dispatched to France, where female missionaries were present in small numbers but dating was strictly verboten. Mission counselors urge their young charges to marry quickly upon returning home, a reflection of the church’s emphasis on marriage, its strict ban on premarital sex, and its emphasis on chastity. In Romney’s case, within three months of returning from his mission he married the girl he’d pledged to wed while in high school.

There’s no evidence that Romney had much experience with the emotionally rough and tumble world of dating, where women can provoke emotional vulnerability in even the manliest of men. At a time when lots of young men were still sowing wild oats, Mitt and Ann were having kids, the first within a year of marriage, while they were both in college at Utah’s Brigham Young University. (The Romneys eventually had five boys, ensuring that Mitt would be spared any confrontations with that alien species—teenage girls—as he got older in his male-dominated household. Even Seamus, the Romneys’ now-famous Irish Setter, was a guy.)

The Mormon-church-owned BYU was hardly the place for Romney to expand his interactions with women. While the women’s movement was rapidly breaking down barriers for women after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which barred discrimination on the basis of gender, BYU maintained a long-standing prohibition on hiring married women of childbearing age, leaving few women as faculty members or administrators.

When Romney arrived on campus in 1969, the school still had a ban on women’s pantsuits. Church leaders had partly designed BYU as a place for women to find husbands and learn skills that would make them better wives and mothers. (It’s still a running joke among female students that they’re attending BYU to obtain an “RM”—or “returned missionary.”)

At the university, Romney spent his free time in BYU’s all-male “Cougar Club,” raising money for the school and leading religious meetings of the club’s members when not in class. After graduating in 1971, Romney entered an elite and virtually all-male joint law and business program at Harvard, where just 10 percent of the MBA students were female. Romney later moved on to the testosterone-fueled world of finance at Bain Capital. He has acknowledged that his firm had few women in positions of power—only about 10 percent of the firm’s vice presidents were women.

Romney carried this guy-centric history into politics. In his first political race, in 1994, Romney’s traditional family and long marriage could have been a selling point, especially given that Ted Kennedy was suffering in the polls largely because of his own issues with women. A few years earlier, Kennedy had been forced to testify in the rape trial of his nephew, William Kennedy Smith, because he had been out drinking with Smith the night Smith was accused of sexually assaulting a woman.

During that Senate campaign, Romney ran as a moderate and tried to cast himself as the anti-Kennedy: a devoted family man who’d never strayed from the path. In a well-meaning attempt to bolster that image, Romney’s mother, Lenore, volunteered to an interviewer that Mitt and Ann had waited until they were married to have sex. Still, Romney lost the women’s vote by historic proportions.

It’s possible that Romney’s straight-laced and pious bearing might have hurt him in that race. Some infamous womanizers have been good politicians perhaps because they were good at connecting with the ladies (see Bill Clinton). Romney seems handicapped in this area. He often comes off on the campaign trail as someone who isn’t terribly interested in listening to ordinary voters. He has a habit of ignoring questions that he doesn’t want to answer. And he doesn’t demonstrate much empathy, a liability that may disproportionately hurt him among women.

Recall the incident in South Carolina in January when an African American woman approached the rope line and told Romney about her economic woes. At such a moment, Clinton might have offered her a big bear hug. Romney offered her cash, pulling $50 to $60 out of his pocket and thrusting it upon her. Romney was clearly trying to be nice, yet the gesture came off as patronizing. It’s a quality that’s likely to be off-putting to women, who are sensitive about having their ideas and complaints dismissed by men.

Eric Fehrnstrom, a spokesman for Romney’s campaign, responded to questions for this story by forwarding a 2004 study showing that when Romney was governor of Massachusetts, he had the highest percentage of female appointees in the country. And Romney has employed women in senior campaign posts. One example is Beth Myers, the longtime Romney adviser who’s heading up his vice presidential search and who served as his chief of staff in Massachusetts.

Romney has indeed shown the ability to take women seriously and to rethink his views of their issues when pressed to do so. In 1993, he was serving as the Belmont LDS “stake” president when a group of feminists in the church were agitating for more equitable treatment. Romney grudgingly met with the 250 women to consider their demands, which included installing changing tables in the men’s room and the opportunity to address the congregation the way men could.

When Romney showed up at the meeting, he brought the tools of his trade: flip charts and markers. His approach, and his follow up, which included implementing a number of the women’s demands in the church, left the female congregants feeling hopeful. Many of them who’ve spoken to the press in recent months point to that meeting as evidence that Romney is capable of being responsive to women’s concerns.

But then there are other stories from his time as a church leader that show different, more domineering interactions with women. Among the most oft-repeated incidents is one in which Romney visited a divorced woman from his church who’d become pregnant with her second child out of wedlock. She wanted the baby and planned to raise it by herself. But Romney informed her that the church believed she should give her child to the LDS adoption agency because she was unmarried. If she refused, the woman recalled, Romney said the church would excommunicate her. She ended up keeping her baby anyway, and later quit the church. (According to The Real Romney, a new book written by a pair of Boston Globe reporters, Romney would later deny that he had threatened to excommunicate the woman. But she told the Globe reporters that Romney’s message “was crystal clear: ‘Give up your son or give up your God.'”) The side of Romney that is capable of making such a demand on a mother may be the part of him that many women voters, consciously or not, find unappealing.

In many ways, Romney is a case study for the old feminist argument that gender equality isn’t just good for women, but good for men, too. His life in the monastery of paternalistic, male-dominated institutions has garnered him great riches and success. But his life in the boy’s club has also given him few opportunities to practice genuinely connecting with ordinary women who make up the female voting bloc—a problem that could doom him in November.