Sardines (Sardina pilchardus) Etrusko25 via Wikimedia Commons

Sardines (Sardina pilchardus) Etrusko25 via Wikimedia Commons

Sardines are considered a sustainable seafood, one of the few fish you can eat guilt-free, right? Well, not exactly. Forage fish like sardines and anchovies are the key players in huge but delicate food webs known as wasp-waist ecosystems. These are so complex and dynamic that it’s questionable whether we have the know-how to manage them well yet. And as we’ve learned the hard way from examples off California, Peru, Japan, and Namibia, wasp-waist ecosystems collapse catastrophically whenever the stresses of climate change intersect with the stresses of overfishing (see Andrew Bakun, et al., below*).

These systems are often driven by multiyear, even multidecadal, climate patterns like El Niño and La Niña—natural boom-and-bust cycles that remain largely beyond our abilities to scientifically manage. And while some overfished wasp-waist ecosystems have recovered after decades of fishing moratoria (California, Peru), others have not (Japan, Namibia). Some, like Peru, collapse repeatedly.

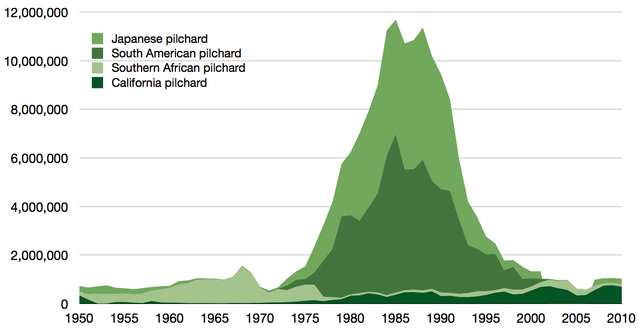

Global capture of sardines in the Sardinops genus in tons, 1950–2010, as reported by the FAO. Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets. Epipelagic via Wikimedia Commons

I wrote about the downside of the sardine fishery in Mexico’s Gulf of California in my latest Mother Jones print piece, “Can One Incredibly Stubborn Person Save a Species?” This is the story of my old friend Enriqueta Velarde’s efforts to save the seabirds and other wildlife of the Gulf. Year after year she’s taken on staggering problems. Today her biggest fear is the rapidly growing sardine fishery:

She’s concerned because the Gulf of California sardine fishery, Mexico’s largest by volume, landed more than a quarter million metric tons the year before. She knows the Gulf is a wasp-waist ecosystem: ecology-speak for a delicate food web dependent on forage fish (sardines and anchovies) that are virtually the only predators of all below them (plankton) and virtually the only prey of the tiers above them (bigger fish, seabirds, marine mammals)…Mexico just received a sustainability certification for its sardine fishery from the Marine Stewardship Council, which would vastly increase market demand in the US. Velarde fears that the fish, keystone to all Gulf species—including humans—will crash.

Tern with fish Badjoby via Wikimedia Commons

But it’s the Marine Stewardship Council, and you can trust what they say is okay to eat is okay, right? Well, not necessarily. As I’ve written here about swordfish, here about Chilean sea bass, and here about pollock, hake, Antarctic toothfish, and krill, there are increasing concerns among scientists about the criteria the MSC is using to certify fisheries as sustainable.

So before you take a bite of that sardine sandwich, you might think about all the truly vast ecosystems—composed of seabirds, bigger fish, seals, dolphins, whales, and sharks—utterly dependent on sardines and their kin. And the fact our fisheries management might not yet be capable of managing what we don’t yet fully understand.

*Papers:

- Andrew Bakun, Elizabeth A. Babcock, Salvador E. Lluch-Cota, Christine Santora, Christian J. Salvadeo. Issues of ecosystem-based management of forage ?sheries in “open” non-stationary ecosystems: the example of the sardine fishery in the Gulf of California. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. 2009. DOI 10.1007/s11160-009-9118-1

- Andrew Bakun. Wasp-waist populations and marine ecosystem dynamics: Navigating the “predator pit” topographies. Prog Oceanography. 2006. DOI:10.1016/j.pocean.2006.02.004