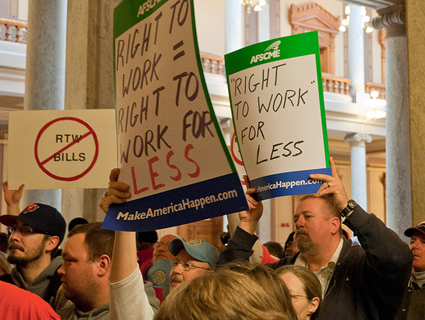

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/afscme/5471721416/in/set-72157626121265364/">Greg Hansen, AFSCME</a>/Flickr

On Wednesday the New Hampshire House of Representatives passed a right-to-work law, returning the issue to Democratic Gov. John Lynch’s desk for the second time in two years. The bane of organized labor for over half a century, right-to-work laws regained momentum in the United States after Republicans won historically sweeping victories on the state level in the 2010 midterm elections. In February, Indiana became the first state in a decade—and the first Rust Belt state—to enact one of the laws.

Jimmy Hoffa, the president of the Teamsters, has said that right-to-work proponents are waging a “war on workers,” and Martin Luther King Jr. called right-to-work a “false slogan” and said the laws “rob us of our civil rights and job rights.” But proponents of the laws believe they’re necessary for the growth of manufacturing and business that can bolster states’ weak economies. A lack of nationwide right-to-work legislation, they argue, has resulted in “abuses of workers’ human rights and civil liberties.”

So what is a right-to-work law, anyway?

The basics

No American worker can be forced to join a union. But most unions push companies to agree to contracts that require all workers, whether they’re in the union or not, to pay dues to the union for negotiating with management. State right-to-work laws make these sorts of contracts illegal, meaning that workers in unionized businesses can benefit from the terms of a union contract without paying union dues. (Under federal law, unions must represent all workers covered by a contract, even if some of those workers are not members of the union and do not pay for the union’s representation.)

Unions are fighting the expansion of these laws, which currently apply in 23 US states. A coalition of lawmakers, manufacturers, tea partiers, and big conservative think tanks want to see them passed in the rest of the US.

The history

In 1947 a Republican-controlled Congress passed the federal Taft-Hartley Act (also known as the Labor-Management Relations Act). This law amended the 1935 National Labor Relations Act so that closed shops—businesses in which every employee was required to be part of the union and pay dues—were no longer legal. This left individual states free to pass laws that prohibited requiring employees in a unionized business to pay dues. These laws are known as right-to-work laws.

The right-to-work slogan originates from a the US Supreme Court ruling Dent v. West Virginia stating that Americans had a fundamental right to pursue an occupation of their choice. The Supreme Court forbid state legislatures from depriving or regulating people’s particular occupation. Later, a newspaper editor from Texas named William B. Ruggles who was anti-union reinterpreted the term to mean the right to work in a unionized business without paying dues. (Ruggles has since become something of a folk hero for the right-to-work movement. There’s even a scholarship named after him at the anti-union National Institute for Labor Relations Research.)

OK, but why are we talking about this now?

Lynch, the Democratic governor of New Hampshire, will likely veto the right-to-work law that recently passed the state House of Representatives. Lynch vetoed a very similar proposal last May, the House’s attempt to override that veto failed last November, and Lynch remains strongly opposed to right-to-work laws, a spokesman told Mother Jones. But elsewhere, right-to-work laws are making headway. In February, Indiana became the first Rust Belt state and the first state in over a decade to adopt a right-to-work law. Of the 22 other states to pass right-to-work laws since 1947, Idaho, which passed a law in 1985, and Oklahoma, which passed one in 2001, are the most recent.

The passage of a right-to-work law in Indiana, which has long had strong unions, represents a new phase of the battle over the laws. As Abby Rapoport recently explained in the American Prospect, most previous right-to-work laws were passed in states without a strong organized labor presence:

“States throughout the South and West soon passed such legislation, and used the laws to prevent unions from gaining a foothold or gaining significant power. The laws never actually dismantled a strong union presence, but instead kept unions out for fear they would upset racial and class structures.”

The Indiana law took on unions in a state where labor’s foothold was once strong and is now “slowly diminishing.” That makes it a perfect place to begin an attack on labor in the Rust Belt, Rapoport argues.

If unions in Indiana lose membership and become weaker because of the law, lower wages might lure manufacturing business from Michigan, where 18 percent of workers are currently represented by organized labor.

A right-to-work movement has also begun to take hold in Michigan, too. As my colleague Andy Kroll has reported, last October legislators unveiled a “right-to-teach” bill that “would let teachers work under union-negotiated contracts without chipping in a dime for the cost of negotiations.” The bill is currently in the Committee on Reforms, Restructuring and Reinventing. The Detroit News reported that Mitt Romney was pushing hard for right-to-work laws when he campaigned through the state before narrowly winning its GOP primary election in February.

Wisconsin is also grappling with a right-to-work law. At the same time he was trying to eliminate collective bargaining for public-sector employees, Gov. Scott Walker floated a right-to-work bill. Now pushback by organized labor and the public on behalf of workers’ rights has Walker facing a recall election.

Who’s supporting the recent right-to-work laws?

Indiana’s legislation appears to have come from the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). As Karen Olsson reported in Mother Jones in 2002, ALEC, which is funded by private corporations, industry groups, and conservative foundations, “gives business a direct hand in writing bills that are considered in state assemblies nationwide.” The group’s model legislation includes Arizona’s SB 1070, and a “truth in sentencing” bill that the Corrections Corporation of America helped draft.

How do these laws affect the economy?

It’s hard to say. The most well-known study on the development of manufacturing in states with right-to-work laws was published by Thomas Holmes in 2000. Holmes compared manufacturing growth or decline on the borders between right-to-work states and states without the pro-business legislation. He found that in right-to-work states, manufacturing employment was higher than in “anti-business” states without the laws. These findings have led supporters like Harvard economics professor Robert Barro to conclude that “right-to-work laws—or, more broadly, the pro-business policies offered by right-to-work states—matter for economic growth.”

However, Mother Jones‘ Kevin Drum says it’s no surprise pro-business states attract more manufacturing:

“[B]usinesses prefer locating in states where costs are low and rules are lax — something I think we all knew already. Of course that’s what businesses prefer. But it says literally nothing at all about whether the United States as a whole would have higher or lower growth if every state either did or didn’t have right-to-work laws.”

Holmes is careful to note that factors like the expansion of railways and trucking and even the invention of air conditioning all played a part in the stronger growth of manufacturing in the Southern and Sun Belt states. Holmes’ findings also don’t mean the laws are good for the economy or the worker in a state over time. A 2011 study by the labor-backed Economic Policy Institute found that wages and benefits are lower in right-to-work states than in non-right-to-work states. Oklahoma has actually seen a reversal of the initial growth in manufacturing jobs since its right-to-work law passed in 2001. The EPI report found that in the cases of “higher-tech manufacturing, to ‘knowledge’ sector jobs, or to service industries dependent on consumer spending in the local economy—there is reason to believe that right-to-work laws may actually harm a state’s economic prospects.”

What’s next?

The New Hampshire bill is unlikely to become law, but that doesn’t mean right-to-work won’t continue to spread. Tea party activists in Ohio are campaigning for a constitutional amendment that would make it a right-to-work state. The group would need 386,000 signatures before the first week of July in order to get the amendment on the November 2012 ballot. According to a Qunnipiac Poll, 54 percent of Ohioans support right-to-work laws.

The Missouri legislature is considering several right-to-work bills. A proposed constitutional amendment in Virginia has been carried over and will be considered in 2013. Virginia is already a right-to-work state but Republicans are determined to enshrine the legislation in the state’s constitution.

After their victory in Indiana, it seems clear that right-to-work proponents have other manufacturing states in their sights. Raymond Hogler, a professor at Colorado State University who’s an expert in labor law, asks, “If it passes in Indiana, why not in Ohio, why not in Minnesota, why not in Michigan?”