Kathleen Flynn/Tampa Bay Times/ZUMA Press

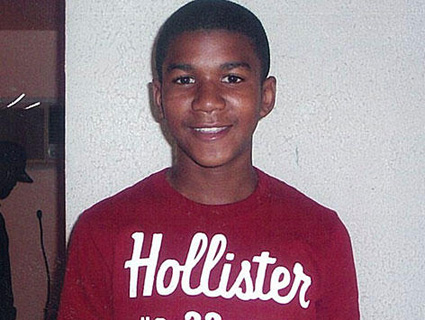

On Tuesday, city officials from Sanford, Florida, trekked to Washington for a meeting on Capitol Hill with a group of black lawmakers and officials of the Justice Department’s civil rights division. The topic at hand: The recently announced investigation of the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was fatally shot in late February by George Zimmerman, a self-appointed neighborhood watch captain, while walking back to his father’s house in a gated community from a local convenience store.

Sanford Mayor Jeff Triplet told the group he’d spent the last few days listening repeatedly to the recording of Zimmerman’s 911 call, according to Rep. Alcee Hastings (D-Fla.), who was present at the meeting. After the shooting, Zimmerman told the police that Martin had attacked him and he had acted in self-defense. Apparently believing his version of events, the Sanford police did not arrest him. But the 911 tape suggested that Zimmerman had pursued Martin, even though he had been warned against doing so by the 911 dispatcher.

When Hastings suggested that Zimmerman might have uttered a racial slur on the call, Triplet pulled a copy of the recording out of a folder and passed it to the DOJ’s assistant attorney general for civil rights, Thomas Perez. Sanford’s city manager, Norton Bonaparte, implored Perez to probe the conduct of the Sanford police.

The inquiry being conducted by Perez’s division and the FBI is focused on the actual shooting, in part to determine whether it was a hate crime. But as questions continue to emerge about the Sanford police department’s handling of this and other racially-charged cases, civil rights leaders have urged the feds to broaden the inquiry to include a civil investigation into possible police wrongdoing. And this is an area Perez knows well. During his two-year tenure at the civil rights division, he has quietly led a federal crusade against police misconduct, pursuing 19 investigations of local police departments—the most in the division’s history.

“During the Bush administration [police misconduct] was not a high priority,” says Richard Jerome, a former Justice Department attorney who now runs the Public Safety Performance Project at the Pew Center on the States. “There certainly were not only fewer cases but the end result of the cases were different.”

Using its authority to compel institutional changes in local law enforcement agencies that have engaged in systemic violations of Americans’ constitutional rights, Perez’s office has helped to overhaul the police department of Puerto Rico and New Orleans police force. (New Orleans police officers shot several civilians in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.) It has scrutinized the Miami and Seattle police departments and exposed the civil rights abuses of Arizona’s notorious anti-immigrant Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

But the inquiry into Trayvon Martin’s death will likely be one of the most high-profile cases of Perez’s tenure, spotlighting a division that just a few years ago was considered among the most politicized sections of the Justice Department.

When Perez took over the civil rights division in 2009, he inherited a demoralized staff that was suffering something akin to PTSD. During the Bush era, political appointees had tried to purge the office of career attorneys they deemed insufficiently conservative and punish those who hung on to their jobs. In the early months of Perez’s tenure, it was not unusual for staffers to break down in his office, recalling past traumas.

“It felt like grief counseling,” says Samuel Bagenstos, who served as Perez’s principal deputy until last August.

Restoring the division to its role as “the conscience of the Justice Department,” as Eric Holder had put it during his confirmation hearing, was a priority of the Obama administration. And choosing Perez, a former career prosecutor who was hired during the George H.W. Bush administration and who used to bust dirty cops and white supremacists, was meant to send the message that it was truly a new day for the division.

“There’s a long bipartisan tradition of civil rights enforcement,” Perez says, “I worked here under Bush I; that [politicization] never happened [then].”

Last month, in an interview with Mother Jones in his Justice Department office, he reflected on his return to the division. Slim and goateed, the 52-year old was nursing a limp—an injury he promptly turned into a punch line.

“I’m often accused of hiring people with civil rights experience, and I do plead guilty to that,” Perez quips, referring to conservative criticism that he has stacked the division with liberals. (Perez has indeed changed hiring practices at the division by putting career attorneys—not political appointees—back in charge of the hiring process, and his right-wing critics claim this leads to hiring attorneys with civil rights experience who tend to be liberals.) “I’m having surgery on my knee next week,” he adds, “and I’m not having a psychiatrist do it, I’m having a surgeon do it.”

Perez’s parents were both exiles from the Dominican Republic. His maternal grandfather, a former ambassador to the United States, was exiled after he denounced Dominican dictator Raphael Trujillo’s massacre of thousands of ethnic Haitians in 1937. Perez’s father also fled the Trujillo regime, later joining the US Army as a surgeon.

“There was a lot of lawlessness in the Dominican Republic,” Perez says. “What my parents taught me was that the hallmark of a thriving democracy was an effective and respectful police force.”

Perez racked up a bunch of high profile cases while a young prosecutor in the division, including the conviction of several neo-Nazis in Texas who went on a murderous hate crime spree in an attempt to provoke a race war. That case netted him a Distinguished Service Award. After a detail on Senator Ted Kennedy’s staff, he left the DOJ in the early 2000s to serve on the Montgomery County Council and on the board of a local immigrant rights group, CASA de Maryland.

“He’s always viewed it as his life’s calling to help vulnerable people,” says Leon Rodriguez, a longtime friend who now runs the civil rights office at the Department of Health and Human Services. Rodriguez previously worked under Perez at Justice, where Rodriguez helped organize a meeting between division attorneys and police chiefs across the country. Perez’s “main message” to the chiefs, Rodriguez recalls, was, “I need to hear from you, I need to learn from you. You’re the guys who live this every day.” Attorneys in the division, who had been stymied during the Bush years, were looking to pursue police misconduct cases that had gone unaddressed. And Perez was looking for a way to conduct these probes vigorously but in a manner that would lead to more effective policing.

The Justice Department has been a focus of conservative ire throughout the Obama administration, and Perez’s nomination was held up for months by Senate Republicans trying to kneecap the president by blocking many of his executive appointments. (Senate conservatives were put off by his immigration work.) Perez could have taken his confirmation battle as a message to lay low and avoid ruffling conservative feathers. Instead, his division has taken an aggressive role in enforcing civil rights laws: blocking restrictive voting measures, securing big money settlements against banks peddling predatory loans to minority customers and service members, filing lawsuits on behalf of bullied gay students, and fighting discrimination against the disabled.

“His tenure is a welcome contrast to the division under the previous administration, which too rarely addressed issues of civil rights and discrimination in a meaningful manner,” says NAACP President Benjamin Jealous.

The division has also taken on rising Islamophobia—intervening in a Tennessee case where local activists seeking to block construction of a mosque argued in court that Islam wasn’t a religion and therefore mosques weren’t entitled to federal exemptions from local zoning laws granted to religious buildings. Perez says his division’s brief in the case, arguing that Islam is in fact a religion, was “one of the saddest I’ve had to file.”

But the division’s unprecedented campaign against police abuses has largely transpired under the radar. But that could all change with the Trayvon Martin case. The Sanford police chief temporarily stepped down on Wednesday, but the local NAACP chapter says the town has a history of discriminatory policing.

In recent meetings with civil rights leaders and legislators, Perez has emphasized that the bar for prosecuting Zimmerman under federal hate crimes law is high. But civil rights groups, including the NAACP, have been pushing the division to pursue a broader investigation covering the practices of the Sanford police. In a sign that he has truly turned around the division, Perez has actually raised expectations.