Downtown Elko: Mojorider2/FlickrAmerica is full of small towns that bolster our national identity even though most of us rarely visit them. They are repositories of authenticity like Flint, Michigan; Treynor, Iowa; and Abilene, Kansas—factory, farming, and ranching towns. Every few years, national politicians parachute into a few carefully selected ones to stake claims to one political mythology or another. Which is essentially what Mitt Romney and Ron Paul were doing this week in Elko, a remote gold-mining town that’s home to 0.7 percent of Nevadans, most of whom could drink whiskey all day long and still kick the shit out of the other 99.3 percent in a bar fight.

Downtown Elko: Mojorider2/FlickrAmerica is full of small towns that bolster our national identity even though most of us rarely visit them. They are repositories of authenticity like Flint, Michigan; Treynor, Iowa; and Abilene, Kansas—factory, farming, and ranching towns. Every few years, national politicians parachute into a few carefully selected ones to stake claims to one political mythology or another. Which is essentially what Mitt Romney and Ron Paul were doing this week in Elko, a remote gold-mining town that’s home to 0.7 percent of Nevadans, most of whom could drink whiskey all day long and still kick the shit out of the other 99.3 percent in a bar fight.

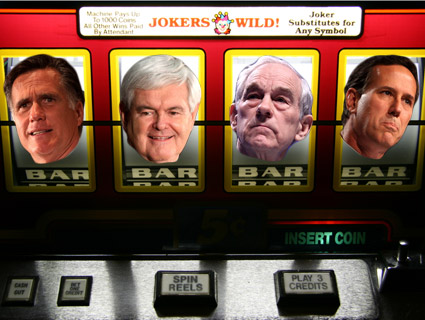

The romance of mining and its close relative, fist-fighting, factors heavily into the Silver State’s brand of rugged individualism. Nevada’s most famous early senator, William Stewart, once bragged of defending a mining claim by tackling an interloper into a ditch and strangling him with a woolen shirt. But while most of Nevada’s prospecting happens at the slots these days, and its most talked-about fist-fights are pay-per-view, Nevadans still look to places like Elko to keep it real. In the lead-up to the 2008 election, Barack Obama visited Elko twice.

Possibly the best window into Elko life is Goldie’s, a watering hole near the downtown casinos where, naturally, the gold miners hang out. A few years ago, I was nursing a beer there when the sloshed tatterdemalion sitting next to me saw it fit to call a guy with a cratered face ugly. Soon I had to get up from my barstool because the drunk’s forehead was about to be pinned against it, his neck oddly immobile in Crater Face’s vice grip.

I moved to the back of the bar. A miner with Barrick Gold, a multinational gold mining company, was drinking Jager Bombs with Nay Nay, an off-duty stripper half his age. Her role in a recent “stripper fight” with some girls at Stockmen’s Hotel & Casino had gotten her 86’ed, she told me. When she returned to Stockmen’s anyway to do a private gig in a hotel room, the staff called the cops and she fled through a second-story window. She wanted to leave town but had no money. “I don’t want to hitchhike because I would have to shoot somebody,” she said, apparently convinced that some pervert would jump her.

The gold miner, a starched cowboy type, had donated $90 to help Nay Nay out. “He’s got money, and a good heart,” the stripper cooed, leaning in to nibble his ear.

“That’s what mining is: We take care of our own,” the miner told me between drags on a Camel. “But we’ve got to keep the government out of our hair so we can take care of our own. That’s just the way it is.”

In Elko, a worker with a high school degree can earn $70,000 a year. That’s no longer true in most parts of America, but then, most of America isn’t sitting on billions of dollars in gold deposits. People want to buy that gold when the economy tanks, which means that Elko cashes in when the rest of the country suffers. So while people in Las Vegas might want the government to make investments in the economy, people in Elko want it to make itself scarce.

“Believe me, if you defer to the government and think that they should tell you how to run your life and how you should spend your money, then I’ll tell you what: We’re not going to get over this,” Ron Paul said in Elko on Thursday. Such a notion is certain to earn praise in Elko, where there isn’t much of a crisis to be gotten over. The big question in today’s Nevada Caucus and November’s general election is how much Elko’s independent streak still influences the mindset of voters in Vegas, where a tourism and a housing slump have created one of the nation’s highest unemployment rates. You don’t need the government, until you do—a lesson that Elkonians might learn the hard way if our national economy ever recovers.