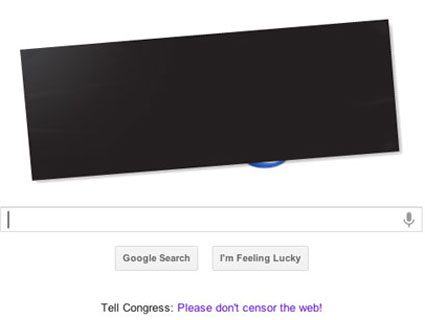

Google blacked out its logo on Wednesday in protest of two Hollywood-backed copyright bills pending in the US Congress.Screenshot

Only two American industries have ever had the clout in Washington to force Congress to ban Wall Street from trading futures on their products. The first was onions—futures trading in no one’s favorite root vegetable was banned in the 1950s after farmers protested that Chicago speculators were manipulating prices. The other ban is more recent: In 2010, at the urging of the Motion Picture Association of America, one of Capitol Hill’s most powerful lobbies, Congress banned movie futures as part of the Dodd-Frank financial regulatory reform bill.

The big studios took on Wall Street—which isn’t known for losing lobbying fights—and won. So this month, when all the big entertainment companies joined forces with Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform and the US Chamber of Commerce, the nation’s foremost big business lobby, to fight for sweeping anti-piracy legislation, it was almost a foregone conclusion that they would get what they wanted.

Instead, Big Hollywood lost. Here’s how it happened.

The bills that topped nearly every big entertainment company’s legislative priority list in 2011 were called the Stop Online Piracy Act (in the House) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (in the Senate)—SOPA and PIPA, for short. They would have allowed copyright owners to force websites they believed were infringing their content right off the internet—you could call it “shoot first and ask questions later” copyright enforcement. The law would even have allowed for allegedly infringing sites to be blocked from the Domain Name System, the internet’s equivalent of a phone book—making it appear as if the blocked site was down or didn’t exist. Entertainment companies loved it—finally, they had a truly powerful weapon to deploy against pirates. But tech companies and venture capitalists warned that the bills could increase costs and stifle innovation, forcing web companies to check every link on their sites—even ones posted by their users—to make sure they didn’t lead to infringing content.

Movies, music, and publications are among America’s most valuable exports—more than $30 billion in 2007—and the industry has a lot of pull in Congress. Nearly half the Senate, including Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.), signed on to the Senate version. In the House, 32 representatives from both parties—including Rep. John Larson (D-Conn.), the fourth-ranking House Democrat, and Lamar Smith (R-Texas), the chairman of the powerful judiciary committee—backed the entertainment industry’s proposal. (You can see supporters and opponents of the bills over at ProPublica’s website.) Maplight.org found that since the beginning of the 2010 election cycle, SOPA’s 32 sponsors took in nearly four times as much in campaign contributions from the entertainment industry than from the software and Internet industries (nearly $2 million versus a little over $500,000). For SOPA opponents, the ratio was reversed—foes of the legislation took about twice as much money from software and internet firms as they did from the entertainment industry.

The White House, which has close ties to the entertainment industry (earlier this year, for example, President Obama appointed famed anti-filesharing lawyer Don Verrilli as solicitor general) seemed to be on board. As the Washington Post‘s Brad Plumer wrote, “These bills seemed all but inevitable.” The House Judiciary Committee held only one hearing on SOPA on November 16. Of the six witnesses invited, only one, an attorney with Google, testified against the bill. PIPA, meanwhile, passed out of the Senate Judiciary Committee with nary a hearing.

Then, as members of Congress fundraised and partied through their winter recess, the wheels started to come off the bus. A few tech journalists, such as Ars Technica‘s Tim Lee, put in yeoman’s work covering the growing controversy. But the most important pressure came from some big names in new media: Craigslist’s Craig Newmark, BoingBoing‘s Cory Doctorow, Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales, Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanian, and so on. In late December, Reddit commenters organized a boycott of GoDaddy, a web-hosting company that backed SOPA. (The company changed its position.) Redditors, BoingBoingers, Craigslisters, and Wikipedians called their members of Congress, and several of the sites, including Wikipedia, began planning a coordinated blackout for Wednesday, January 18, to coincide with a hearing that Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), a SOPA opponent, was holding on the bill.

One draft for a “blackout screen” for Wikipedia, which went dark on Wednesday in protest of two Hollywood-backed copyright bills pending in the US Congress. Wikipedia

One draft for a “blackout screen” for Wikipedia, which went dark on Wednesday in protest of two Hollywood-backed copyright bills pending in the US Congress. Wikipedia

Venture capitalists and tech investors weighed in, too. “All of a sudden, this group of investors who’d been apolitical…found themselves dealing with issues that had political consequences,” says Brad Burnham, a venture capitalist with Union Square Ventures who opposes SOPA. On Twitter, techie-cum-media types like ex-Huffington Post CEO Eric Hippeau (a major tech investor himself) railed against the bills.

Minds changed. Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.), the chair of the powerful House budget committee, announced on January 9 that he would oppose the bill (after taking nearly $300,000 from pro-SOPA donors). Ryan’s aspiring 2012 opponent, Rob Zerban, had raised tens of thousands of dollars through a Reddit campaign denouncing Ryan’s position on the legislation.

Late Thursday, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), the lead sponsor of the Senate bill, announced that he would consider dropping the DNS-blocking provisions from the bill. Late on Friday, Smith, SOPA’s sponsor, did Leahy one better, removing the provision altogether. Not long after, six Republican senators—including two cosponsors—released a letter they wrote to Reid, asking him to hold off on a January 24 vote to end debate on PIPA and move to passage.

By this weekend, the writing was on the wall. Rep. Eric Cantor (R-Va.), the House Majority Leader, announced that SOPA would not come for a vote in the House before the controversy over the bill is resolved—essentially killing it for the time being. The White House issued a statement opposing significant portions of the bills. And Issa canceled the hearing planned for Wednesday, saying he’s “confident” the bill is dead in the House.

Big Hollywood isn’t entirely beaten yet. PIPA, the Senate legislation, could still get a vote and move closer to becoming law, and a modified version of SOPA could conceivably come to the House floor at some point in the future. Wikipedia, Reddit, MoveOn.org, Mozilla (the maker of the Firefox web browser), the blogging platform WordPress, and others are still planning to go dark on Wednesday, just in case. But as of right now, a combination of grassroots activism, blogging, tweeting, boycotts, and the mere threat of having to scroll through 1,500 LOLCats without Icanhazcheezburger (another boycott supporter), seems to have beaten an avalanche of money and lobbying. Those 1950s onion farmers would be proud.

UPDATE 1 (Jan. 18, 2:10 p.m. EST): As currently written, SOPA and PIPA would still hang heavy compliance costs on Internet companies large and small.

That’s because copyright holders could get a court order demanding the removal of entire sites with pirated content, as opposed to only removing the content in question. But the bills would also leave it up to websites to police themselves for potential violations. According to Julie Samuels, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, that’s an expensive proposition, particularly for fledgling startups that don’t boast expensive in-house legal teams. “The cost of doing business, and risks associated with doing business under SOPA and PIPA, would have a serious chilling effect on innovation, further hampering whatever economic recovery we’ve seen thus far,” Samuels said.

A panel hoted by the Progress Change Campaign Committee on Tuesday honed in on this still-very-live issue. Rep. Darrel Issa (R-Calif.), one of the leaders of the anti-SOPA/PIPA contingent, argued that the government can prevent piracy through existing trade courts and anti-piracy laws. “We think we can do 80 percent of the good with almost no trauma,” Issa said.

Venture capitalist Brad Burnham, a managing partner at Union Square Ventures, pointed to the tangle of litigation that’s bound to ensnare companies. “A social network, a payment processor, any service on the Internet that links to anything…takes on the risk of this frivolous litigation,” Burnham said. SOPA and PIPA “broaden the risk beyond the actual endemic industry…these bills actually make intermediaries liable for the protection of the interest of those incumbent industries.”

UPDATE 2 (Jan. 18, 4:05 p.m. EST): Late on Tuesday, the red dominoes in the Senate began to fall.

Sen. Scott Brown (R-Mass.) tweeted out his intention to vote no on PIPA. Then on Wednesday morning, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) backed off his support for PIPA—through Facebook. Rubio affirmed his “strong interest in stopping online piracy,” while urging Congress to continue “promoting an open, dynamic Internet environment that is ripe for innovation and promotes new technologies.” Sen. John Cornyn, chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, quickly followed suit, also taking to Facebook to say that it is “better to get this done right rather than fast and wrong.”

As of Wednesday afternoon Republican Sens. Roy Blunt (Mo.), Orrin Hatch (Utah), Jim DeMint (S.C.), and John Boozman (Ark.) had also joined the Senate’s anti-anti-piracy club. And on the SOPA front, two of the bill’s original co-sponsors, Ben Quayle (Ariz.) and Lee Terry (Neb.), pulled their support on Tuesday.

“Of the 29 lawmakers that have announced opposition to the bills, 26 are Republican,” Patrick Ruffini, the president of digital firm Engage, tweeted on Wednesday. The Weekly Standard‘s Michael Goldfarb summed up the GOP’s retreat with a tweet of his own: “SOPA/PIPA collapse among the most dramatic I can recall…….”