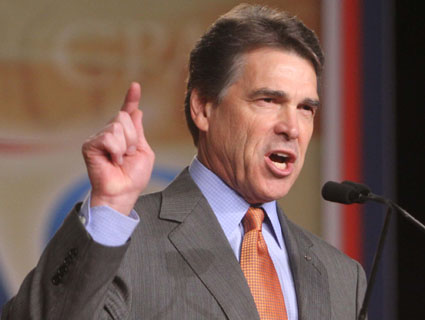

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/talkradionews/6221214232/sizes/m/in/photostream/">TalkMediaNews</a>/Flickr

Rick Perry takes Texas pride in being a climate change denier—and his administration acts accordingly.

Top environmental officials under Perry have gutted a recent report on sea level rise in Galveston Bay, removing all mentions of climate change. For the past decade, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), which is run by Perry political appointees, including famed global warming denier Bryan Shaw, has contracted with the Houston Advanced Research Center to produce regular reports on the state of the Bay. But when HARC submitted its most recent State of the Bay publication to the commission earlier this year, officials decided they couldn’t accept a report that said climate change is caused by human activity and is causing the sea level to rise. Top officials at the commission proceeded to edit the paper to censor its references to human-induced climate change or future projections on how much the bay will rise.

John Anderson, the oceanographer at Rice University who wrote the chapter, provided Mother Jones with a copy of the edited document, complete with tracked changes from top TCEQ officials. You can see the cuts—which include how much sea level rise has increased over the years, as well as the statement that this rise “is one of the main impacts of global climate change”—here and embedded at the end of this story. As the document shows, most of the tracked changes came from Katherine Nelson, the assistant director in the water quality planning division. Her boss, Kelly Holligan, is listed as a reviewer on the document as well.

Holligan and Nelson are top managers at Perry’s commission; lower-ranking staff at the agency had already approved the document, according to the publication’s editor. The changes came only after the two managers reviewed the issue. TCEQ’s commissioners, who are direct political appointees of the governor, select the top managers at TCEQ. Although the director and assistant director jobs aren’t technically political appointments, those hires are usually vetted by the governor’s office.

Anderson, whose complaints were first reported by the Houston Chronicle on Monday, says that the cuts to his paper were political and had nothing to do with science. The research underlying the study was peer-reviewed and is part of a decadelong study Anderson has conducted in partnership with other scientists. The Geological Society of America published the scientists’ results in 2008. “I was a bit astonished,” Anderson tells Mother Jones. “Really this paper is just a review of papers we published previously. There’s no denying the fact that sea level rise has significantly accelerated. The scientific community is not at all divided on that issue.”

TCEQ even deleted a reference to the fact that the bay is currently rising by 3 millimeters a year—five times faster than the long-term average. The edited version that TCEQ sent back also killed a line noting that the bay’s “future will be strongly regulated by the now rising sea,” as well as the factual assertion that the disappearance of the wetlands is “due mainly to direct human intervention.” The officials also cut out the statement that the water level rise “is one of the main impacts of global climate change.”

Anderson has refused to let TCEQ publish the heavily edited version of his work. “It would not have been a worthwhile paper,” he says. “It would not have said anything.”

Jim Lester, the co-editor of the State of the Bay and vice president of the Houston Advanced Research Center, notes that the scientists self-censored before submitting the paper to TCEQ, removing references to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a favorite target of climate skeptics) and largely avoiding the question of whether humans were causing the climate to change. But that wasn’t enough to keep the paper out of the commission’s crosshairs. The report was supposed to be published in 2010, as the title of it suggests, but it has been delayed. Lester and his co-editor have also said they don’t want their names attached to something that is factually inaccurate. “It damages our scientific credibility,” Lester said.

It’s not surprising that people appointed by Perry, the climate deniers’ favorite climate denier, would excise references to climate change from a scientific paper. But the commission’s response to the Chronicle‘s request for a comment was pretty classic:

TCEQ spokeswoman Andrea Morrow gave no reason for the deletions in an e-mail response, saying only that the agency disagreed with information in the article.

“It would be irresponsible to take whatever is sent to us and publish it,” she said.

The commission’s edit is reminiscent of efforts by the George W. Bush administration to suppress climate science. Top political appointees at the White House edited documents to downplay link between greenhouse gas emissions and global warming and to make the science sound more uncertain. In another instance, the Bush administration edited the congressional testimony of the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to remove references to public health concerns tied to climate change.

Anderson says his chapter and the entire publication were written to provide accurate, useful information to Texas state policymakers. He pointed to neighboring Louisiana, where coastal erosion has reached a crisis point and decision makers are struggling to deal with it.

“Sea level doesn’t just go up in Louisiana. We’re the next in line,” he says. “We are in fact starting to see many of the changes that Louisiana was seeing 20 years ago, yet we still have a state government that refuses to accept this is happening.”