In June 2010, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush traveled to Columbus, Ohio, to give the commencement speech for the Electronic Classroom of Tomorrow, the state’s largest virtual charter school. ECOT, which provides K-12 online education for kids who never set foot inside a classroom, was celebrating its 10th anniversary and its largest graduating class—nearly 2,000 kids. Naturally, the event, held on the campus of Ohio State University, was webcast for those who couldn’t make it.

Bush served up the usual graduation platitudes about the future. Then he hit on the reason he was saluting this particular school: digital learning. It was, he said, nothing short of a revolutionary approach, a way to meet “the unique needs of each student so that their God-given abilities are maximized, so they can pursue their dreams armed with the power of knowledge.”

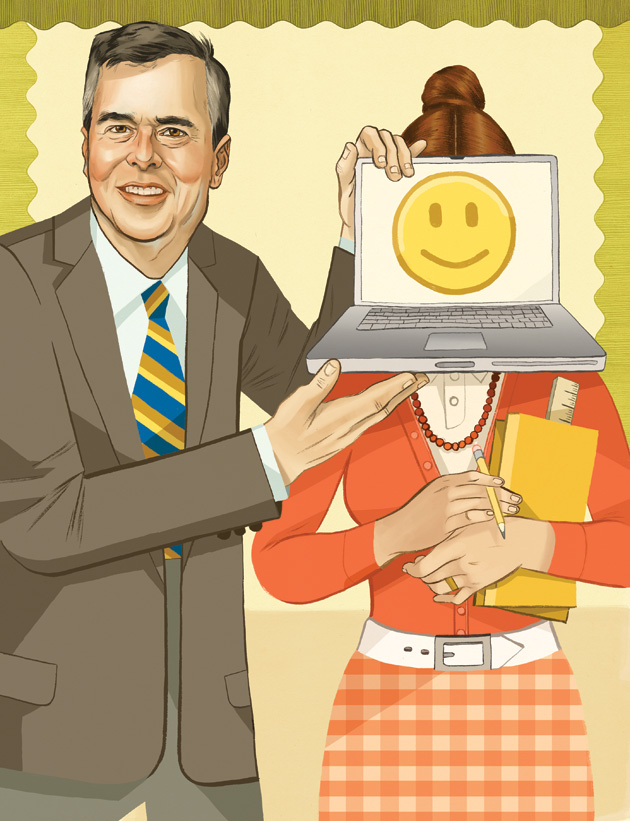

It wasn’t the first time Bush had praised the wonders of online education. Over the past year, he’s emerged as one of the nation’s most prominent boosters of virtual schools, touring the country to promote technology as an instrument of creative destruction against the public school system. Last December, he teamed up with former West Virginia Gov. Bob Wise, a Democrat, to launch a new initiative called Digital Learning Now, which is aimed at tearing down legal barriers to public funding for virtual classrooms.

Bush has couched his initiative in the bipartisan language of reform, claiming it will strengthen public education by making it more efficient, affordable, and accountable. It’s the kind of “21st-century thinking” that had Republicans begging him to run for president earlier this year—and if it helps position him for national office and connect him with potential corporate donors, so much the better. But beneath the rhetoric, the online-education push is also part of a larger agenda that closely aligns with the GOP’s national strategy: It siphons money from public institutions into for-profit companies (including those that are supporting Bush’s initiative). And it undercuts public employees, their unions, and the Democratic base. In the guise of a technocratic policy initiative, it delivers a political trifecta—and a big windfall for Bush’s corporate backers.

Many of the companies supporting Bush’s online-learning advocacy run virtual schools or provide online curricula and are hoping to cash in on the exponential growth in the sector, once a niche market for home-schoolers, child actors, and kids suffering from afflictions that prevented them from attending school; between 2009 and 2010, online-school enrollment jumped nearly 40 percent (PDF). But they have faced considerable obstacles to their expansion plans—everything from lawsuits by teachers’ unions to state laws limiting enrollment in virtual classrooms. That’s where Bush has come in, using his considerable political cachet to sell lawmakers and others on the online-learning vision.

So far, many states have approached the model cautiously—and for good reason. Some online schools have been beset with allegations of fraud (also a trend among charter schools; see “Schools for Scoundrels“). Many educators also question the wisdom of encouraging kids to spend even more time glued to a screen. But there’s a bigger issue still: Many online schools simply aren’t very good, ranking in some states among the most troubled schools. ECOT is Exhibit A.

In December 2010, Bush’s Digital Learning Council—a group of industry execs, policymakers, and education officials convened by Digital Learning Now—issued a report (PDF) detailing the “10 elements of high quality digital learning.” On the list was a call for state policymakers to “hold schools and providers accountable for achievement and growth.” If kept to that standard, ECOT would likely have been shut down years ago.

With more than 10,000 kids, ECOT is bigger than some of Ohio’s 609 school districts. But its test scores rank above those of just 14 other districts. In 2010, barely half of its third-graders scored (PDF) proficient or better on state reading tests, and only 49 percent scored proficient in math, compared with state averages of 80 percent and 82 percent, respectively. ECOT’s graduation rate has never exceeded 40 percent. (“The method used to calculate the official graduation rate does not consider students who take more than four years to graduate from high school,” an ECOT spokesman says. “ECOT enrolls many students who are years behind their peers before they enroll with ECOT. ECOT graduates a large percentage of its population.”)

The school also has a dubious track record in other areas. A 2001 audit (PDF) conducted after its first year of operations found that while the state had paid it to educate more than 2,000 students during one month, a mere seven kids had actually logged on to ECOT’s computer system; state auditors couldn’t verify that the rest of its student body even existed. In 2002, state officials forced ECOT to repay Ohio $1.7 million for these and other violations.

In Ohio, ECOT’s charter prohibits it from opening physical classrooms, a restriction that seriously curbs its growth. After all, there are only so many parents in a position to stay home all day to make sure the kids stay off Facebook and do their work.

ECOT, though, has found a way around this. It has enrolled students in places that serve at-risk kids (who are also more likely to fetch higher school reimbursement rates), such as homes for pregnant teens and residential addiction-treatment centers. Taking a creative view of its contract, which allowed students to “supplement” their home learning by using an ECOT computer at a designated location, it even set up a computer lab in an old gas station. The state investigated three ECOT centers in 2006, looking into allegations that the labs violated a host of laws. (ECOT, which had contracted with a third party to operate these centers, ultimately shut them down.)

According to a lawsuit filed against the school by another company, one of the people helping ECOT broaden its student body was its head of “alternative learning communities,” Alex Kadenyi, a man with a lengthy rap sheet that included convictions for resisting arrest and various drunk-driving offenses. In 2007, while working for ECOT, Kadenyi was arrested for smuggling drugs into the Medina County jail. He pleaded no contest and was given probation, which he later violated by testing positive for cocaine.

ECOT has performed reliably on one front—as a cash cow for the businesspeople backing it. ECOT was founded by William Lager, a former office supply company executive with no background in education. (Lager, a member of Bush’s Digital Learning Council, declined an interview request.) ECOT receives about $64 million annually in state money, and a sizable chunk of that ends up in the coffers of Lager’s other businesses. In 2010, ECOT paid his companies, IQity and Altair Learning Management, a total of $12 million (PDF) for providing curriculum and other services.

Lager has plowed some of his earnings into politics. Since 2001, he has steered nearly $1 million to various candidates in Ohio. He donated about $200,000 last year to key members of the General Assembly, primarily Republicans, and to the Democratic and Republican state parties. In 2009, he gave $10,000 to the GOP in Florida, where his companies also do business with public schools. If Bush ever does run for the White House, Lager will be a good friend to have in a key state.

Jeb isn’t the first Bush to take up the education reformer mantle. When George W. Bush ran for Texas governor in 1994, he campaigned on school reform to highlight his “compassionate conservatism.” And brother Neil Bush founded an educational software company in 1999 that ultimately raised $23 million from investors, including his parents.

The company, Ignite Learning, sells purple multimedia machines known as Curriculum on Wheels, or COWs. School districts, lobbied heavily by Neil, used No Child Left Behind money to buy the equipment during his brother’s administration. In 2006, Barbara Bush donated money to the Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund—with the mandate that it be used to buy Neil’s products for several Houston schools that had taken in Katrina evacuees.

Like his brother George, Jeb needed a marquee issue when he made his run for governor in 1994. In that race, his platform included advocating for speedier executions and closing the state education department. At one candidates’ forum, an African American woman asked what he’d do for the black community. He famously replied, “Probably nothing.”

Carrying just 4 percent of the black vote, Bush lost the race by a percentage point. Soon thereafter, he teamed up with the local Urban League to found the state’s first charter school, branding himself as an education reformer. When he ran again in 1998, there was no mention of killing off the ed department. This time he prevailed.

As governor, Bush focused on a number of controversial education reform measures, including giving public schools letter grades based on students’ test scores. In 1999, when the grading system was first put in place, his own charter school received a D. By 2008, the school had earned a C- and was $1 million in debt; the state shut it down.

After leaving the governor’s office in 2007, Bush started a foundation devoted to education reform. In 2010, it raised $5.9 million, $1.7 million of which went to a two-day conference for legislators. The confab was partially bankrolled by corporations that would benefit from the policies Bush was advocating. At this year’s conference Rupert Murdoch, who sees a big market in online learning (see “Fox in the Schoolhouse“), was the keynote speaker.

Bush’s digital-learning initiatives have also drawn support from companies hoping to cash in on the virtual-education boom, including charter school operators, online-curriculum providers, and tech firms like Apple, Dell, Google, Intel, and Microsoft.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Digital Learning Now report reads like an industry wish list. It calls for jettisoning caps on virtual-school enrollment and removing some teacher licensing rules; allowing students to take unlimited virtual classes from for-profit providers; and expanding use of digital textbooks and online testing.

Alex Molnar, the director of publications at the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) at the University of Colorado-Boulder, says these policy prescriptions are part of a corporate-driven agenda to access public education funds. “These folks talk about a free market,” he says, “but they couldn’t exist without taxpayer dollars. There is a limited audience for this. You have to get policymakers to force people into it.”

To that end, you have to get policymakers to buy in—and that’s the area where Bush has excelled. Bennet Ratcliff, a political consultant who once produced ads for Bill Clinton and now does PR work for Bush’s foundation, says Digital Learning Now is all about “advocating for policies in the states and in districts that would promote digital learning. For instance, it could be talking to boards of education, it could be talking to state chiefs, it could be talking to governors, district [superintendents], legislators.” None of this, he hastens to add, constitutes lobbying: “I do need to be very clear about that. This is an advocacy and education effort about digital learning. What we are not doing is lobbying.” When I asked him who was actually doing the talking, he replied, “Elves.”

The elves scored their first legislative coup in March, when Utah’s Legislature passed a bill, based almost entirely on the Digital Learning Now blueprint, that provides more opportunity for high school students to take online courses. A few months earlier, Bush had visited Utah to make the case for virtual schools to state legislators and to address Gov. Gary Herbert’s Education Excellence Commission. According to education activist Robyn Bagley, that support was key in engineering the bill’s passage. When supporters feared that Herbert might veto it, she says, Bush was on standby to make a governor-to-governor call: “They were there if we needed them.” Bush also published an op-ed in the Deseret News congratulating legislators for putting “Utah and its students at the forefront of K-12 digital learning policy in the country.”

The governor signed the bill. Several of Bush’s Digital Learning Council members will benefit from the new law, including the online education company K12 Inc., which already provides curriculum materials for one virtual school in Utah; its lobbyists, according to Bagley, were also “helpful with the bill.”

But Utah was just the start. With an assist from Digital Learning Now, Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin passed laws this year allowing online-education companies to access more public funds. Some even require public school students to take online classes in order to graduate. Others are considering similar laws. In July, after Ohio’s Republican governor, John Kasich, signed legislation supported by Digital Learning Now, Bush issued a statement praising politicians who’d ensured that “more students in the Buckeye State will have the opportunity to achieve their God-given potential.”

When Bush evangelizes about digital learning, he emphasizes the potential for every student to get an “individualized” and “high-quality” education. But many digital-learning products are not actually tailored to individual students or schools—nor are they particularly high quality. Take the lessons offered by K12, which was cofounded by former Education Secretary William Bennett with help from onetime junk-bond king Michael Milken. With 81,000 students using its curriculum in 27 states, K12 has experienced explosive growth. In the past three years, its business has expanded 72 percent; it’s predicting $500 million in revenue for fiscal year 2011.

K12’s website offers sample lessons, and I worked through a handful for kindergartners and first-graders. The lessons looked like PowerPoint slides. One instructs parents to rustle up crayons and scissors so that “Sarah” can cut out pictures of sheep after being read a poem on the topic. K12 tells parents to ask Sarah things like, “What kinds of animals are in this poem?”

After that, parents are supposed to read the student Make Way for Ducklings. Parents are told to ask, “Why did Mrs. Mallard decide not to hatch her eggs in the public gardens?” Then, K12 instructs parents to have Sarah draw a nice place for a duck to live. Lesson complete! This 21st-century online assignment could just as easily have been an old-fashioned correspondence course.

Lessons for middle schoolers are marginally better. An eighth-grade lesson on Romeo and Juliet involves clicking through a series of slides about Shakespeare and answering some multiple-choice questions. In one section, students are asked to choose a definition of “loins.” According to K12, the correct answer is “families.” (Presumably the dictionary definition might offend the home-schooling base.) There’s one chance for students to do their own writing, but the program doesn’t include an opportunity to have someone read it. Perhaps that’s Mom’s job.

In 2004 (PDF), NEPC fellow Susan Ohanian created three online student identities in a K12 school and took all of the first- and second-grade history classes offered as a research project. “The adult has to do a lot of work,” she says. “I complained bitterly about the amount of stuff you had to print out for the child to color.” And that vaunted individualized education? “Every once in a while I reported that my Johnny didn’t get it,” Ohanian says. “They just said repeat the lesson until you get it right.”

Angelique Smith, a Pennsylvania mother who enrolled her allergy-prone daughter in a K12 school for kindergarten through second grade, was similarly disappointed. “It’s more the parent teaching them,” she says.

In an April study (PDF), the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University reviewed the academic performance in Pennsylvania’s charter schools. Virtual-school operators have been aggressively expanding in the state for more than a decade, making it a good place for a study; around 18,700 of the state’s 61,770 charter school students were enrolled in online schools. The results weren’t promising.

The virtual-school students started out with higher test scores than their counterparts in regular charters. But according to the study, they ended up with learning gains that were “significantly worse” than kids in traditional charters and public schools. Says CREDO research manager Devora Davis, “What we can say right now is that whatever they’re doing in Pennsylvania is definitely not working and should not be replicated.”

Bush’s digital-learning advocacy is the natural extension of a crusade he began more than a decade ago, when he became a high-profile advocate for school vouchers. In 1999, he helped push through a Florida law that would provide students attending failing public schools with “opportunity scholarships,” which could be used at private and religious schools. The courts repeatedly found the voucher program unconstitutional and finally killed it off in 2006, shortly before Bush left office. Soon after, Bush’s former chief of staff and the head of his foundation, Patricia Levesque, led an attempt to eliminate the legal obstacles to vouchers by way of ballot initiatives. That, too, failed.

Virtual schools work very much like voucher systems. In most states, these schools receive per-student funding that would normally go to a student’s home district. This can wreak havoc on public school budgets—which, to Bush and others working to privatize elements of the education system, may be exactly the point. In a December interview with Nick Gillespie, editor of the libertarian magazine Reason, Bush said he sees digital learning as “a transformative tool to disrupt the public education system, to make it more child-centered, more customized, more robust, more diverse, more exciting.” He told National Review two months later that “the unions see [digital learning] as an even bigger threat than vouchers because it’s such a disruptive idea.”

Teachers and their unions are indeed concerned about the rise of digital schools, fearing that educators will be relegated to peripheral roles facilitating students’ online work. It’s already happening in Florida, where last year’s budget cuts made it difficult for the schools to meet class-size rules (originally passed in 2002 over Bush’s vehement objections). Unable to hire more teachers, some schools in the Miami-Dade district required students to take online classes at school, with only an aide to keep tabs on them.

As it stands, in many virtual schools, students rarely hear from their teachers. At the Insight School of Wisconsin, which was recently purchased by K12, students need only sign in to the school website and/or communicate with a teacher once every three days to prove they’re actually attending. A state legislative audit found that 16 percent of the virtual teachers surveyed had contact with individual students as little as three times a month. At one point, K12 even outsourced paper-grading to a contractor in India.

Many online schools also have exceedingly high student-teacher ratios; teachers surveyed by the Wisconsin Legislature reported dealing with online classes of more than 100 kids. The Ohio Virtual Academy, run by K12, has one teacher for every 51 students.

Virtual educators are also often paid far less than their public school colleagues. The average teacher salary in Ohio is about $56,000; at ECOT, it’s $34,000. In regular Ohio public schools, teacher salaries can make up 75 percent of the budget; at ECOT, teachers comprise just 17 percent of the school’s budget. The figure is even lower at K12’s Ohio Virtual Academy—11 percent.

While many virtual schools skimp on teacher pay, they spend considerable sums on something public schools don’t: advertising. The Wisconsin audit discovered that one school, iQ Academy Wisconsin, dropped $424,700 on ads to drum up more business during the 2007-08 school year.

Despite all this—and despite online schools’ track record of undercutting traditional Democratic constituencies—Bush has persuaded a fair number of Democrats to join his cause. Top on the list of converts is Bob Wise, the former West Virginia governor, who credits Bush for putting digital learning on the map. “The reality of the situation is that the only way we reach vast populations with high-quality education is with the effective application of technology,” he says. Bennet Ratcliff, the former Clinton ad man now doing PR for Bush’s online-learning campaign, says the former governor has latched on to a bipartisan issue with wide appeal: “It’s not a big battle or argument when people get down to brass tacks.”

And a bipartisan issue with wide appeal (and a pool of deep-pocketed donors) is exactly what a candidate-in-waiting needs as he bides his time. In the National Review‘s glowing cover story in February all but urging him to run for president, the American Enterprise Institute’s Frederick Hess (a member of Bush’s Digital Learning Council) noted, “Jeb Bush is a case study in how to stay relevant when you’re out of office.” In this area, anyway, Bush can provide a useful lesson.