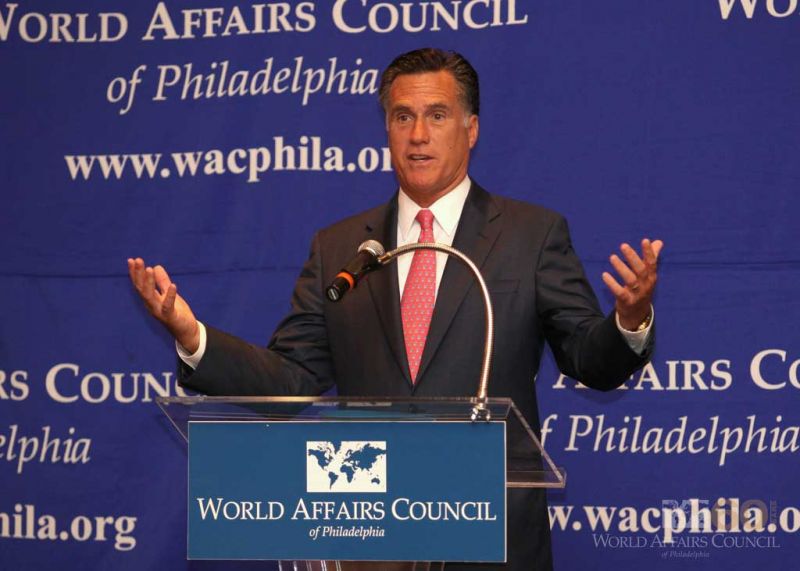

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/mittromney/6069980831/in/photostream">Mitt Romney</a>/Flickr

Tea partiers don’t really seem to like Mitt Romney. This isn’t all that difficult to understand: He is from Massachusetts, has said some pretty liberal things over the years, and was at one point proud of a piece of health care legislation that was eerily similar to the Affordable Care Act signed into law by President Obama in 2010. Those aren’t the kinds of things that sell really well at tea party rallies, and Romney, recognizing this, has for the most part avoided those kinds of events.

Until Sunday. The former Massachusetts governor addressed a crowd of about 150 here at a Tea Party Express rally in Rollins Park. Things went, well, better than they could have. Romney, joined by his wife, Ann, spoke for about 15 minutes, delivering a speech that managed to appeal to the crowd without pandering to them too brazenly. He noted—twice—that he’s not a career politician (a not-so-veiled shot at fellow candidate Texas Governor Rick Perry) and touted his business experience and work with the 2002 Winter Olympics. He cracked a joke about enticing Californians to move to Massachusetts to enjoy its superior business climate (Perry says the exact same thing about Texas), and he offered up some patriotic red meat by telling the story of the time he received a fallen soldier at Boston’s Logan Airport and looked up to see an entire terminal with their hands on their chests. The event’s most memorable line might have come from Ann, who said of her initial reluctance for another presidential run, “Mitt knew not to listen to me because I said that after every pregnancy.”

Oh, and he recited four lines from this poem by Samuel Walter Foss:

Bring me men to match my mountains;

Bring me men to match my plains, —

Men with empires in their purpose,

And new eras in their brains.

Still, it wasn’t all rosy. Romney was also greeted by a man dressed up as a dolphin, or perhaps some variety of porpoise, standing prominently stage right wearing a t-shirt calling Romney a “flip-flopper.” (Flipper also had a pair of yellow flip-flops, in case the metaphor was unclear.) Also there was former Nevada Senate candidate Sharron Angle, tagging along in an SUV-and-trailer combo called the “Team Hobbit Express” and hoping to sell some copies of her book Right Angle. She was careful to not say anything overtly positive about Romney when asked. Volunteers from FreedomWorks, Dick Armey’s corporate-backed tea party outfit, roamed the crowd handing out seven-page lists showing “just how unfriendly he has been over the years to the ideas the tea party holds dear.” (Among his heresies, “Romney signed in to law a smoking ban” and “ran on raising the minimum wage and putting in place automatic increases.”)

Even Romney’s warmup act, former Louisiana Governor Buddy Roemer—who is also running for president—took a few veiled shots at him, warning that candidates who receive million dollar lump-sum donations will be beholden to their donors. (Roemer wins spin points for noting that while only four percent of Granite Staters have heard of him, a full three percent said they like him.)

They call him Flipper Photo by Tim Murphy

They call him Flipper Photo by Tim Murphy

“I’ll write somebody else in or I won’t vote,” says Joe Coutermarsh, of Vermont, spitting out tobacco juice. “He’s not a tea partier. He’s using this as a publicity stunt.” Coutermarsh, on the other hand, is a tea partier, although that term’s so 2010. “I’m a hobbit, as Obama calls us.” It was the Wall Street Journal and not Obama that called tea partiers “hobbits,” but the point stands: Romney’s an outsider with whom tea partiers will never be fully satisfied. He’s John McCain to a group of people who really don’t really like John McCain.

Ralph Zazula, holding up a sign urging Romney to quit the race, made the trip up to Concord from Bedford, Massachusetts, which gives him the distinction of having actually lived in Romney’s big government hellscape for four years. He did more than just support Romney in his 2002 gubernatorial campaign—”I stood there in the snow and begged him to run,” he says. “I was threatened to get beaten up at Fanueil Hall. I took a day off and lost a day’s pay—so I was passionate!” All of which gives his cardboard plea for the candidate to drop out of the race a bit more credibility. “I like Mitt a lot,” he says. “It’s not personal.”

Not everyone hated Romney. “I saw the propaganda from FreedomWorks,” said Romney supporter Corey Lewandowski, of Windham, New Hampshire. “But here’s the thing: They are a group that’s not involved in New Hampshire. They’re not invested in New Hampshire. They can say whatever they want.” But four months before the first meaningful primary votes will be cast, there is an underlying problem that the polls only seem to validate: Romney is the only Republican candidate in New Hampshire whom activists will go out of their way to warn you about.

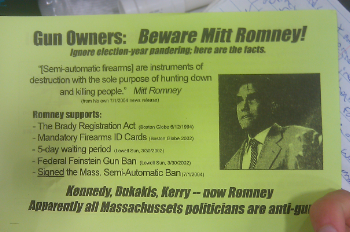

This, for instance, is a flier being handed out by the New Hampshire Firearms Coalition, a sort of local NRA, at the Concord Gun Show on Saturday:

“Gun Owners: Beware Mitt Romney!” Photo by Tim Murphy

“Gun Owners: Beware Mitt Romney!” Photo by Tim Murphy

For his part, Romney, who has a reputation for saying whatever his audience wants to hear, kept things fairly straightforward. He left to an ovation, supplied mostly by an army of about 50 blue-shirted supporters (and one poodle)—and he did it without calling Social Security a Ponzi scheme or threatening to beat up the chairman of the Federal Reserve.