The winners: Acropora corals. Credit: Albert Kok at Wikimedia Commons.

The winners: Acropora corals. Credit: Albert Kok at Wikimedia Commons.

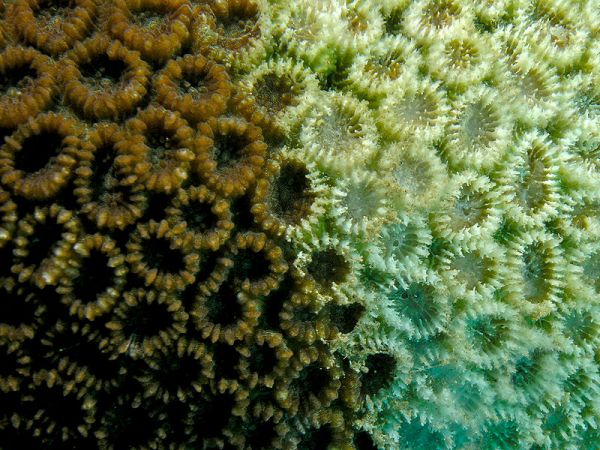

After 14 years of tracking coral colonies at Sesoko Island, Okinawa, Japan, through two coral bleaching episodes—1998 and 2001—the big coral winners and losers on the reef have been announced…

- The winners: Porites, faviids, and Acropora colonies

-

The losers: pocilloporids

Except it’s not that simple, the authors of a new study warn. Since 14 years is hardly the long long run.

The losers: Pocillopora corals. Credit: Mila Zinkova at Wikimedia Commons.

The losers: Pocillopora corals. Credit: Mila Zinkova at Wikimedia Commons.

In a new paper in the current issue of MEPS we get a sense of what happens in the short long term aftermath of a big coral bleaching event.

Background: Coral bleaching occurs when water temperatures rise, stressing the coral animals enough to expel their symbiotic partners—the zooxanthellae. These single-celled plants give corals their beautiful colors and help feed them through photosynthesis. In some plant-animal partnerships, the zooxanthellae entirely feed their corals, making those species more vulnerable to bleaching.

In the past 30 years, rising sea surface temperatures have stressed and bleached corals worldwide. Yet few researchers have looked at what recovery looks like over time—whether the species of corals that fare better in the short term also fare better in the long term.

A partially bleached faviid coral. Credit: Nhobgood at Wikimedia Commons.

A partially bleached faviid coral. Credit: Nhobgood at Wikimedia Commons.

At Sesoko Island, the researchers found that although species richness recovered after 10 years, the composition of coral species on the reef had changed. The pocilloporids were nearly completely gone. Among their other findings:

- Short-term winners were generally heat-tolerant encrusting and massive corals, like Porites, faviids, and small (<5 cm/2 in) Acropora colonies.

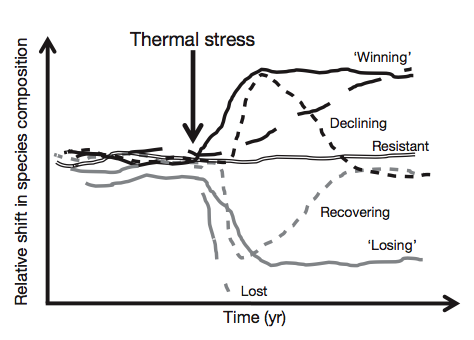

- Ten years after the thermal disturbance the community was still structurally different from the original community, consisting of a combination of survivors that were either:

Tolerant to stress

Surviving as fragments that experienced rapid regrowth

Regionally persistent colonies that recruited locally

Credit: R. van Woesik, et al. MEPS. DOI:10.3354/meps09203.

Credit: R. van Woesik, et al. MEPS. DOI:10.3354/meps09203.

The last point is interesting because it means that having healthy reef neighbors enabled some species to recover—thanks to seeding from nearby islands.

Yet even the short long term winners may not survive the long long term. The authors close with these strongly cautionary words:

The present study suggests that as the oceans warm even further, the coral assemblages will change. Reefs may soon essentially only support heat-tolerant coral species. The narrowing of genetic diversity within communities is likely to impact other dependent species such as fishes and crustaceans, especially if important reef-building branched corals, such as Acropora, Stylophora, Pocillopora, and Porites cylindrica, become rare on account of their inherent sensitivity to thermal stress. Bleaching may also become punctuated over the next several decades. In the short term, the remnant yet hardy populations may show some resistance to the higher water temperatures, and bleaching may be reduced for a decade or more if Acropora and pocilloporids are removed from local reefs. However, reduced bleaching may give false hope because once the inevitable temperature threshold of the remnant communities is surpassed, widespread coral mortality will follow. Given that even the hardiest coral genera have their limits, global temperature increases will eventually lead to an exponential rate of local, regional and global reduction of coral species. To what extent this reduction of coral species will occur will depend on how rapidly and by how much the ocean temperatures increase, which depends on the fossil-fuel-emission pathway that humans choose.

Coral recovery underway on a reef. Credit: Bruno de Giusti at Wikimedia Commons.

Coral recovery underway on a reef. Credit: Bruno de Giusti at Wikimedia Commons.

The paper:

- van Woesik R, Sakai K, Ganase A, Loya Y (2011) Revisiting the winners and the losers a decade after coral bleaching. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 434:67-76. DOI:10.3354/meps09203.