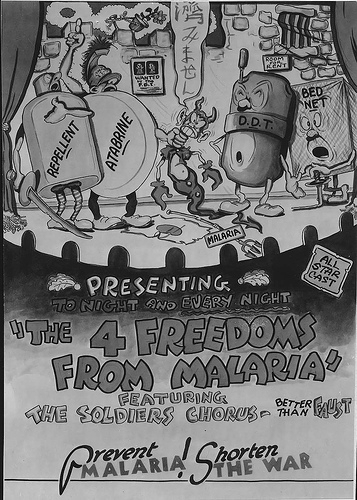

This week, another solution takes the stage.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/7438870@N04/1449303356/sizes/m/in/photostream/">otisarchives2</a>/Flickr

By 1951, the US had eradicated malaria stateside with the help of a few smart doctors and a healthy smattering of good, old-fashioned DDT. But today, many parts of the world are still fighting vigorously against a disease that kills nearly a million people every year—most of them children in Africa—and the mosquito species that carries it. The weapons at their disposal include nets, a sticky insecticide sprayed onto the interior walls of homes, and even lasers.

This week, scientists in the UK might have hit on another, surprisingly simple eradication technique: reduce the size of the mosquito population. I know what you’re thinking: “Well, obviously.” But the new research suggests that, rather than trying to kill mosquitoes themselves, we should prevent them from ever coming into being in the first place. To do that, the scientists injected a batch of mosquito eggs with a compound that turned off the gene behind sperm production; when males were hatched, they produced no sperm. No sperm, no larvae, fewer mosquitoes. The added bonus is that female mosquitoes typically mate only once in their lives, and the study found that the absence of sperm did not seem to change that behavior.

“Targeting fertility is a good way to proceed and it’s a good alternative to what’s already there,” study co-author Flaminia Catteruccia of Imperial College London said.

Because the turned-off gene is unique to mosquitoes, she said, there’s no risk that the sterility could be passed up or down the food chain. Moreover, there’s little chance that such an artificially deflated mosquito population would disrupt ecosystems (for example, by depriving mosquito-eaters of a food source), because malarial mosquitoes are only a few species out of several hundreds. Indeed, she said, the ecological impact of sterilization would be less severe than that of insecticides.

Catteruccia cautioned that in its current form, the method is too laborious to be effectively deployed in the field. Each egg had to be injected individually, and a complex fluorescent marking system was in place to double-check that the procedure had been successful in each male. For obvious reasons, the sterility is not passed down from one generation to the next, so releasing sterile males would need to be a continuous process. The next step, she said, is figuring out how to embed the sterilization in females, who would then pass it on to all their male progeny, lessening the burden on technicians in the field. She was optimistic that with proper funding, a viable field system could be available by 2020.