Photos: New Bethany Alumni; Barbed Wire: Brian Hagiwara/Getty Images

One day last November, a group of teenage girls dressed in long khaki skirts and modest blouses stepped onto the stage at an Independent Fundamental Baptist church in Maryland where Jeannie Marie (a military spouse who asked that her last name not be used) attended services with her family. The young women, visitors from a Missouri girls’ home called New Beginnings Ministries, sang old-time hymns, recited Scripture, and gave tearful testimonies about their journeys out of lives of sin. Headmaster Bill McNamara spoke, too, depicting the home as a place where girls could get on track academically, restore broken relationships, and learn to walk with God.

New Beginnings describes itself as a character-building facility for “troubled teens,” and what Jeannie Marie heard in church that day was that this might be a place for her daughter to heal. While jogging earlier that year, the 17-year-old (whom I’ll call Roxy) had been pulled into a vehicle and assaulted by a group of men. Since then, she had begun acting up at home, as well as sneaking out and drinking. Two weeks after seeing the girls in church, Jeannie Marie and her husband left Roxy in McNamara’s care with the promise that she would receive counseling twice a week and stay at New Beginnings no longer than two months. “It sounded like a discipleship program,” Jeannie Marie recalls. “A safe place where a daughter can go to have time alone to find God and her direction.”

Instead, Roxy found herself on the receiving end of brutal punishments. A soft-spoken young woman, blonde and blue-eyed with a bright smile, Roxy confided to me that she found it easier to discuss her ordeal with a stranger than with the people closest to her. She told me how, in her first weeks at the academy’s Missouri compound—a summer-camp setup in remote La Russell, population 145—she and other girls snuck letters to their parents between the pages of hymnals in a local church they attended, along with entreaties to congregants to mail them. When another girl snitched, Roxy said, McNamara locked some girls in makeshift isolation cells, tiled closets without furniture or windows. Roxy got “the redshirt treatment”: For a solid week, 10 hours a day, she had to stand facing a wall, with breaks only for worship or twice-daily bathroom trips.

She was monitored day and night by two “buddies,” girls who’d been there awhile and knew the drill. They accompanied her to the shower and toilet, and introduced her to a life of communal isolation and rigid discipline. Girls were not allowed to converse except from 6 to 9 p.m. each Friday. They were not allowed contact with their families during their first month, or with anyone else for six months. By that time, Roxy said, most girls are “broken,” having been told that their families have abandoned them, and that the world outside is a sinful, dangerous place where girls who leave are murdered or raped.

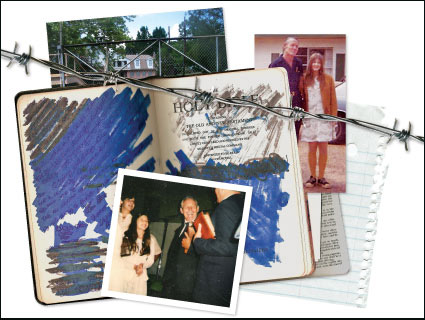

A traveling chorus from New Bethany. “I felt like they stole whatever was inside me that allowed me to trust,” says a former resident. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]The girls’ behavior was micromanaged down to the number of squares of toilet paper each was allowed; potential infractions ranged from making eye contact with another girl to not finishing a meal. Roxy, who suffered from urinary tract infections and menstrual complications, told me she was frequently put on redshirt, sometimes dripping blood as she stood. She was also punished with cold showers, she said, and endless sets of calisthenics after meals.

A traveling chorus from New Bethany. “I felt like they stole whatever was inside me that allowed me to trust,” says a former resident. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]The girls’ behavior was micromanaged down to the number of squares of toilet paper each was allowed; potential infractions ranged from making eye contact with another girl to not finishing a meal. Roxy, who suffered from urinary tract infections and menstrual complications, told me she was frequently put on redshirt, sometimes dripping blood as she stood. She was also punished with cold showers, she said, and endless sets of calisthenics after meals.

Back in Maryland, Jeannie Marie was unaware of her daughter’s plight. Her letters went unanswered—only one of Roxy’s replies got past the academy’s censors. Getting through by phone also proved challenging, and calls were monitored. A billing dispute with New Beginnings’ staff didn’t make things any easier. It was two months before she and her husband could arrange a conference call with Roxy and the staff. They asked Roxy if she wanted to come home. Surrounded by her disciplinarians, the girl replied that she had to stay—that New Beginnings was good for her. The call dissolved into a shouting match between Jeannie Marie and McNamara—who finally declared that he would only discuss the matter with her husband.

When I phoned New Beginnings to ask about the family’s allegations, a staffer referred all questions to Wesley Barnum, the academy’s attorney, who did not return my repeated calls.

A week or so after the disastrous conference call, Jeannie Marie traveled to La Russell with a friend who’d heard about places like New Beginnings—sketchy teen homes drawn by Missouri’s laissez-faire policy toward faith-based residential facilities. Authorities in the state are barred from inspecting the homes or even keeping track of them. (New Beginnings has operated under multiple names in Florida, Mississippi, and Texas.) “It’s hard to understand it, but faith-based is just taboo for regulation,” says Matthew Franck, an editor at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, who authored an investigative series on the state’s homes in the mid-2000s. “It took decades of work to get just the most minimal standards of regulation at faith-based child-care centers,” he adds. “I just knew that when certain lobbyists would stand up to say, ‘We have a concern about how this affects faith-based institutions,’ the bill was immediately amended—it was a very Republican legislature—or it would immediately die. That’s still true.” (Missouri isn’t alone. In April, Montana state Rep. Christy Clark, who campaigned on a “faith and family” platform, joined 11 other Republicans in scuttling a bill that would have regulated religious teen homes; a mother of three, she cast the homes’ residents as unreliable witnesses who “struggle with truthfulness.”)

When Jeannie Marie arrived at New Beginnings, she had a tense conversation with the school counselor, who insisted that Roxy wanted to stay. She extracted her daughter nonetheless. The school’s effects on Roxy were striking, Jeannie Marie told me. When they stopped at a restaurant on the way home, she robotically asked for permission to speak or to use the bathroom. After months of punitive mealtimes, including five-minute “force feeding” sessions for girls on redshirt, she wolfed her food. Back in Maryland, she showed signs of an eating disorder, self-destructive behavior, and severe depression. “I was only there for three months,” Roxy said, “but because we weren’t allowed to keep track of time, it felt like six.”

Desperate for a way out, she’d attempted suicide—many of the girls did, she added nonchalantly, if only for the chance to get taken to a hospital and beg for outside help. “They take away any feeling that you are capable of doing anything outside the home,” she said. “You have this sense of total isolation: There’s no way out of it, you’re there for the rest of your life.”

New Beginnings is emblematic of an unknown number of “troubled teen” homes catering to the Independent Fundamental Baptist community—a web of thousands of autonomous churches linked by doctrine, overlapping leadership, and affiliations with Bible colleges like Bob Jones University. IFB churches emphasize strict obedience and consider teen rebellion an invention of worldly society, so it’s little surprise that families faced with teenage drinking, smoking, or truancy might turn to programs promising a tough-love fix. Fear of government intrusion—particularly on account of the community’s “spare the rod, spoil the child” worldview—is so pervasive that IFB congregations are primed to dismiss regulatory actions against abusive facilities as religious persecution.

The entrance to New Bethany’s Louisiana compound. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]New Beginnings and numerous other Christian reform schools trace their lineages to Texas radio evangelist Lester Roloff, who founded the Rebekah Home for Girls in Corpus Christi back in 1967, employing disciplinary tactics that were adopted by dozens of imitators. He also pioneered girls’ singing groups as a way to promote Rebekah Home—the “Honeybee Quartet” was featured in his daily revivalist radio broadcasts. But back at the hive, Roloff’s wards were often subjected to days in locked isolation rooms where his sermons played in an endless loop. They also endured exhaustive corporal punishment. “Better a pink bottom than a black soul,” Roloff famously declared at a 1973 court hearing after he was prosecuted by the state of Texas on behalf of 16 Rebekah girls. (The attorney general responded that he was more concerned with bottoms “that were blue, black, and bloody.”) Later that year, a former student testified that a whipping at Rebekah Home left inch-high welts on her body.

The entrance to New Bethany’s Louisiana compound. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]New Beginnings and numerous other Christian reform schools trace their lineages to Texas radio evangelist Lester Roloff, who founded the Rebekah Home for Girls in Corpus Christi back in 1967, employing disciplinary tactics that were adopted by dozens of imitators. He also pioneered girls’ singing groups as a way to promote Rebekah Home—the “Honeybee Quartet” was featured in his daily revivalist radio broadcasts. But back at the hive, Roloff’s wards were often subjected to days in locked isolation rooms where his sermons played in an endless loop. They also endured exhaustive corporal punishment. “Better a pink bottom than a black soul,” Roloff famously declared at a 1973 court hearing after he was prosecuted by the state of Texas on behalf of 16 Rebekah girls. (The attorney general responded that he was more concerned with bottoms “that were blue, black, and bloody.”) Later that year, a former student testified that a whipping at Rebekah Home left inch-high welts on her body.

In a 1979 standoff that would become the stuff of fundamentalist folklore, Roloff declared his cause “the Christian Alamo,” organizing hundreds of supporters into barricades to keep state officials off his compound. The ensuing church-state battle outlived Roloff, who died in a plane crash in 1982. The home relocated to Missouri three years later, returning to Texas in 1998 after then-Gov. George W. Bush deregulated the activities of faith-based groups there.

Rebekah Home eventually closed, and New Beginnings opened in Florida soon after, under the watch of a couple who had worked with Roloff for 35 years. They were Wiley Cameron (who later served on Bush’s peer-review board for Christian children’s agencies in Texas) and his wife Faye (who was banned from working with children in the Lone Star state). Bill McNamara and his wife eventually took over, and when state officials began investigating the home, they moved New Beginnings to Missouri. “Because I used to listen to [Roloff] on the radio, and read about the great girls coming out of his place, I thought maybe this was God’s thing for Roxy,” Jeannie Marie remembers. “I didn’t know to do deeper research, because, I thought, these are Baptists, these are my people.”

This past February, parents at Amelia Academy, a Virginia Christian day school with no IFB affiliation, made an unpleasant discovery: One of the teachers had been accused by former students at the New Bethany Home for Boys and Girls—a Roloff-inspired facility in Louisiana—of participating in physical punishments decades earlier. After a heated school-board meeting where parents demanded an investigation, Amelia headmaster George Martin went online to solicit stories from New Bethany alumni. (A criminal background check came back clean, and the teacher, who denied abusing any children, remains at Amelia.)

One of the students Martin contacted was Teresa Frye, now a 43-year-old mother of four. She told me of her upbringing in North Carolina, where an IFB preacher named Mack Ford occasionally visited her church. He would arrive with a school bus full of teenagers from his girls’ home in Arcadia, a Louisiana town of 2,700. They made a striking presentation—young women in white blouses or dresses, with lovely voices, singing and offering dramatic testimonies. They spoke of living as prostitutes and drug addicts before finding salvation at New Bethany, where they now rode horses and studied the Bible. Churchgoers emptied their wallets, pouring out “love offerings” to sustain Ford’s mission.

Interviews with a half-dozen former students indicate that most of the girls were merely “rebellious” teens—like Frye, who at age 14 began resisting her strict Baptist parents. In 1982, they sent her to New Bethany, and her 10-year-old sister followed soon after. The girls found themselves at a remote compound bordered by a rural highway and ringed with barbed wire. There was no horseback riding. Their studies consisted of memorizing Scripture (mistakes were punishable by paddling) and a rote Christian curriculum. Discipline ranged from belt whippings to being forced to scrub pots with undiluted bleach or—in the years after Frye attended—wearing painfully high heels for weeks on end, or running in place while being struck from behind with a wooden paddle, according to alumni.

Then there was the “big sister treatment”—established students, directed by staff, inflicting punishments on the newbies. “It was basically like in the military, where they do a ‘blanket party,’ throwing a blanket over your head, and your teammates beat the crap out of you to make you get back in line,” says Lenee Rider, a New Bethany alum whose father, an IFB pastor, frequently hosted Ford’s touring chorus during his training.

Rider recalled one new girl she was assigned to supervise: Angela was a firebrand who’d arrived at New Bethany straight out of a mental institution and became such a target of staff and “big sister” discipline that she twice attempted suicide. First she jumped through the glass of a second-story window. Later, she slashed her wrists. Rider found her in the bathroom, surrounded by shards of broken mirror. After a housemother bandaged Angela’s arms, Rider said, she heard the girl being beaten down the hall. When Rider tried to apologize, Angela asked why she hadn’t just let her die.

In 2000, Rider created a New Bethany “survivor” forum comprising as many as 400 former residents and staff. Among them was Cat Givens, an Ohio radio technician who stayed at New Bethany in 1974 and became so shell-shocked by the routine of punishment and submission—and the spectacle of runaways being returned by the police and handcuffed to their beds—that she lost her will to resist. “After a while, I was so brainwashed I didn’t even want to run,” she told me. “I figured this was God’s plan.”

Karen Glover, a Navy veteran who attended Indiana’s Roloff-inspired Hephzibah House as a girl, described what she calls “the bowel and bladder torture.” The girls were given bran, made to drink lots of water at breakfast, and then denied bathroom access until lunchtime. There was no apparent reason for this treatment, Glover says, save reminding the girls who was in charge. Dave Halyaman, assistant director of Hephzibah House, would not respond directly to Glover’s claims. Instead, he offered to put me in touch with two pastors who had daughters there. “We have our critics, but also people who think very well of us,” he said.

New Bethany founder Mack Ford proved even less talkative. I reached him at home on three occasions, and he hung up on me twice. He refused to discuss any allegations of abuse. (“I don’t know anything about that,” he said.) Nor would he divulge the name of his attorney or agree to have his attorney contact me.

Ford operated a separate New Bethany home for boys in Longstreet, Louisiana. Clark Word, now 44, was sent there when he was about 15. On his second day, he recalls, he watched administrator Larry Rapier punch a boy of 10 or so in the mouth for wetting his pants on the bus to Sunday worship. Violence was the norm, Word says, and students were expected to enforce discipline. In one memorable 1982 incident, a student named Guy disappeared from the school after he was badly beaten with golf clubs by other students, leaving Guy’s terror-stricken friends to wonder whether the staff had finished him off. (Rapier’s ex-wife Dee told me she sent Guy to recover at her mother’s Texas home before returning him to his parents.)

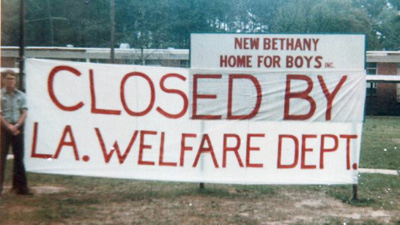

In 1982, when New Bethany’s leaders shut down the home to avoid a state inspection, they had a volunteer staffer put up this banner. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]My attempts to track down Larry Rapier proved fruitless. But Dee Rapier confirmed the atmosphere of physical and psychological torment at the facility she ran with her former husband. “Larry had a room that used to be a storage place that was six by eight, or eight by eight, that he called ‘solitary confinement,'” she told me. (A former staffer called them “revival rooms.”) Misbehaving boys were put in isolation, given a can to pee in, and forced to listen to hours of taped sermons, Word remembers.

In 1982, when New Bethany’s leaders shut down the home to avoid a state inspection, they had a volunteer staffer put up this banner. [MORE: See photos of life at New Bethany.]My attempts to track down Larry Rapier proved fruitless. But Dee Rapier confirmed the atmosphere of physical and psychological torment at the facility she ran with her former husband. “Larry had a room that used to be a storage place that was six by eight, or eight by eight, that he called ‘solitary confinement,'” she told me. (A former staffer called them “revival rooms.”) Misbehaving boys were put in isolation, given a can to pee in, and forced to listen to hours of taped sermons, Word remembers.

After Word had been there for almost seven months, his “watch” escaped. Police normally returned runaways to the home, but the severity of the boy’s injuries led state officials to investigate. Rapier, who had continued running the school while free on bond in a 1981 child-abuse case (the charges were eventually dropped), sent the other boys away—some went home, some were placed at kindred facilities. School records, Dee Rapier told me, were shredded.

The school reopened the next year in Walterboro, South Carolina, under a new administrator, Olin King. Word’s 14-year-old brother, Doug, was sent there soon after for stealing a neighbor’s Playboy magazines. In 1984, police were tipped off by escapees about a rope “chain gang” working the gardens, and beatings with PVC pipe—which, the boys darkly joked, stood for “pound victims cruelly.”

Officers raided the compound and discovered Doug Word bound, in his underwear, on the floor of a dark and padlocked isolation cell. King and his assistant were charged with kidnapping, unlawful neglect, and conspiracy. They pled no contest to false-imprisonment charges and received suspended sentences and probation. “I took that case personally,” recalls Emory Rush, the now-retired sheriff’s chief deputy who led the raid. “I abhorred the fact that they would do children like they were doing them.”

The raid grabbed headlines, but the school reopened again, this time merging with Ford’s New Bethany girls’ school in Arcadia. Over the next two decades, both the girls’ and boys’ branches would close and reopen several times more—swelling at times to hundreds of students.

Authorities and watchdog groups are familiar with the patterns—the state-hopping, the frequent openings and closings—but “people forget,” says Deputy Rush. Indeed, Olin King (who through his wife declined to comment for this article) now runs a North Carolina home for preteen boys under the names King Family Ministries and Second Chance Ranch. New Bethany alumni alerted local authorities to King’s past and his new location. But Maj. Durward Bennett, the former chief deputy of the local sheriff’s department, told me they didn’t see fit to investigate King’s new home because, Bennett erroneously insisted, King was never convicted, and North Carolina has never deemed him unfit to operate a home.

The operators of shady homes do seem to have a knack for avoiding major prosecution. Just last year, prosecutors in Blount County, Alabama, charged Jack Patterson—a Roloff protégé and founder of a boys’ home called Reclamation Ranch—with aggravated child abuse. Then-prosecutor Tommy Rountree said deputies raided the ranch after an escapee alerted them to beatings, isolation cells, and armed staffers who would “go hunting for runaways.”

The raid uncovered handguns and rifles, leg irons, and handcuffs; 11 boys were taken into state custody. But because deputies neglected to seize Patterson’s computer, which the escapee claimed contained files of videotaped beatings, Patterson was able to plead his felony charges down to a “verbal harassment” misdemeanor carrying a $500 fine. He now runs a home for adult men on the Reclamation Ranch property and a girls’ home called Rachel Academy in neighboring Walker County—and is in the process, he says, of opening new homes in Ohio, Florida, and Michigan.

Rountree, who bluntly calls Patterson “evil,” says he and his staff traveled extensively to gather testimony from former Reclamation Ranch kids, but found little usable evidence. He blames this on the contracts parents sign—one mother who owed Patterson money feared that “Big Jack” might sue her if she cooperated with the state—as well as fervent support for men like Patterson among many Christian fundamentalists.

Patterson insists that the abuse allegations were bogus and denies using any corporal punishment or isolation tactics. Reclamation Ranch, he says, had “a family-style atmosphere.” He points to his misdemeanor sentence as proof that the prosecution was politically motivated. As for the shackles and weapons, “I never knew how they got there,” he told me. “My fingerprints were never on them.” But he adds that he fired three staff members shortly before the raid for abusive methods: one for shooting a rifle over the boys’ heads, one for “roughhousing” a resident and shoving him into a locker, and one for placing a boy in handcuffs.

Despite the bad PR, Christian reform facilities appear to have no trouble attracting new recruits. Bruce Gerencser, who spent 25 years as an IFB pastor, recalls Lester Roloff visiting his Bible college to promote the homes. Once Gerencser reached the pulpit, he saw teen-home directors showing up at pastors’ fellowship meetings to peddle their services; Hephzibah House director Ron Williams—who now hosts a show on the Bob Jones University radio station—visited Gerencser’s own church with a girls’ chorus. “I would give literature to parents about the schools,” says Gerencser, who is now a critic of the IFB mindset. “I’d never visited those homes, but you took at face value that people were doing good things. I look back on it and see how irresponsible that was.”

In September 2008, Clark Word began doing some research on New Bethany. He found Rider’s online community, which included Dee Rapier, the wife of his old nemesis. Now 65 and living in Texarkana, Texas, Dee had pleaded for forgiveness from her former charges. She had posted her phone number for anyone wanting to talk, drawing a cautious but earnest call from Word. “She wanted to know how I’d turned out,” Word recalls. “She said, ‘So many of you turned out to have alcohol and drug problems.’ I didn’t tell her at that point that she’d ruined my life.”

Indeed, a lot of the kids who were forced to regale churchgoers with phony addiction stories turned to drinking and drugs to help them cope with what happened at the schools. After leaving Hephzibah House, Karen Glover ended up becoming both an addict and a sex worker for a time. Teresa Frye “did my body weight in drugs” after her stint at New Bethany. Lenee Rider “stayed drunk for a year.” Angela, her old watch, died of complications from cirrhosis in 2008. “I felt they stole whatever was inside me that allowed me to trust,” Rider says.

NEW BETHANY FINALLY shut down its remaining Louisiana compound after years of police raids and legal battles. Its board of directors reportedly voted for closure in 2001, but rumors abound that New Bethany boarded girls as late as 2004. That the home’s own former staffers aren’t sure of the year speaks volumes about an industry so poorly regulated that state officials can’t verify whether certain homes even exist.

Survivors and their families complain that the state authorities seem uninterested in prosecuting abuses at the homes—particularly in Missouri, where some facilities settle so far out in the sticks that state agencies are unaware of them. Nanci Gonder, press secretary for the Missouri attorney general’s office, suggests that officials are hamstrung—private schools don’t require state accreditation and are not governed by laws regulating the public schools. “Our only authority is through the Missouri Merchandising Practices Act, which would include concerns like false advertising,” she says.

That’s the backdoor channel that Donna, a military wife and mother of eight in the Northeast, ended up taking. In 2007, she sent her 14-year-old daughter, Kelsey, to the Circle of Hope Girls Ranch in Humansville, Missouri. The girl had been caught drinking with school friends. Donna, spread thin with her husband on his third Iraq deployment, and fearful of a family history of substance abuse, worried that Kelsey was headed for trouble. At Circle of Hope, Kelsey was allegedly ordered to do pushups in horse manure, restrained and sat upon by staff members, and pushed to make false confessions about promiscuity. Donna estimates that the family spent $20,000 on her three-month stay—tuition and fees, plus the cost of counseling and educational catch-up required after Kelsey came home. Jay Kirksey, Circle of Hope’s attorney, would not address Donna’s claims, but he extended an invitation to come visit. “Unfortunately, just like there is in the public schools and public sector, there are disgruntled parents, who, instead of looking at their own child and situation, choose to talk about the school,” he said.

Donna told me that she has approached at least seven state and federal offices—including the Missouri AG—seeking action against Circle of Hope for stating falsely on its website that it was state-registered, a claim she says gave her the confidence to send Kelsey there. “I’ve been fighting this. I’ve been calling everyone,” Donna says, “and I want to know: Why is nothing being done?”

“Our Consumer Protection Division is still looking into the issue,” Gonder responds. “The school cooperated in providing information, but their information was different from hers.”

At both the state and federal levels, the “troubled teen” industry—religious and secular—enjoys quiet support from many politicians. (Key fundraisers for Mitt Romney’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns hail from Utah’s teen-home sector.) Local courts promote the homes as an alternative to juvenile detention, and facilities can collect a variety of state and federal grants.

Congress has tried, and so far failed, to rein in the schools. In 2007, a spate of deaths at teen residential programs prompted a nationwide investigation by the Government Accountability Office. Its findings—which detailed the use of extended stress positions, days of seclusion, strenuous labor, denial of bathroom access, and deaths—came out in a series of dramatic congressional hearings over two years. The result was House Resolution 911 (PDF), which proposed giving residents access to child-abuse hotlines and creating a national database of programs that would document reports of abuse and keep tabs on abusive staff members.

Hephzibah House’s Ron Williams and Reclamation Ranch’s Jack Patterson urged supporters to fight the bill. In an open letter, Williams argued that it would “effectively close all Christian ministries helping troubled youth because of its onerous provisions.” They were joined by a group called the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, which opposed HR 911 on the grounds that states—despite all evidence to the contrary—are best situated to oversee the homes. The bill passed in the House, but stalled in a Senate committee.*

In March 2010, the House passed the Keeping All Students Safe Act, a bill that would have banned the use of seclusion and physical or chemical restraints by any school that benefits from federal education money. (It, too, died in the Senate.) Andy Kopsa, who covers abusive homes in her blog, Off the Record, noted that GOP members whose districts host tough-love schools rallied against the act. They included former Indiana Rep. Mark Souder (Hephzibah House), Alabama Rep. Robert Aderholt (Reclamation Ranch, Rachel Academy), and North Carolina Rep. Virginia Foxx (King Family Ministries), who testified: “This bill is not needed…The states and the localities can handle these situations. They will look after the children.”

In the absence of federal action, alumni of the teen institutions have been trying to expose the abuses. In 2008, Susan Grotte, a Hephzibah House alum, led some 60 survivors in campaigning for its closure; they wrote to newspapers and picketed outside the county courthouse in Warsaw, Indiana, near where the school is located. “We have laws to protect people from illegal incarceration,” she says, “but apparently not if you’re a teenage girl.” In the past year, New Bethany alums staged a reunion trip to confront the Fords, and they joined with members of kindred groups such as Survivors of Institutional Abuse to gather and publicize survivor stories. SIA is planning a 2012 convention for adults who have been through “lockdown teen facilities.”

Back in Maryland, Jeannie Marie has introduced Roxy to the survivor community in the hope that sharing her ordeal will help her recover. “I show her the websites,” Jeannie Marie says, “and tell her, ‘Look how long ago this happened to these girls: 5, 10, 15, 20 years ago. These girls are just letting go and finding freedom because they started discussing this.’ I said, ‘Roxy, don’t wait that long.'”

Clarification: The version of this article that appeared in the magazine left the impression that Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) was concerned that HR 911 could interfere with parents’ rights. In fact, in a letter to the constituents inquiring about the bill, Brown had simply noted that this was a concern of the bill’s opponents, not necessarily his own view.