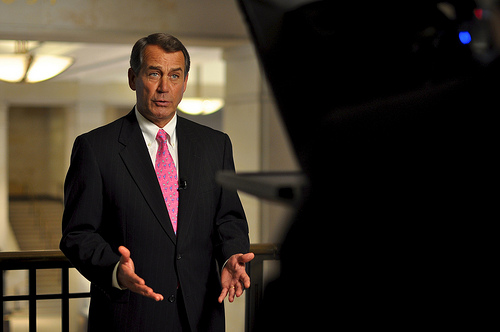

Republican Conference/Flickr

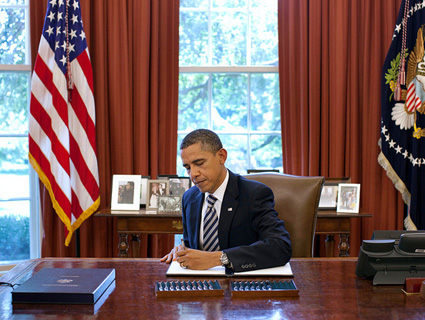

When House Speaker John Boehner’s office released an outline of the final debt deal he hashed out with President Obama, one message was clear: This plan would not raise taxes.

In the near term, Boehner was right. The Budget Control Act, as the debt ceiling deal is officially known, contains no outright tax increases and does not eliminate any tax loopholes or corporate subsidies, including $4 billion a year for large oil corporations. But Boehner and other Republicans say the debt ceiling bill goes even further: They claim it’s “effectively…impossible” for the “supercommittee” of 12 lawmakers tasked with cutting the deficit by $1.5 trillion more to raise taxes at all, tipping further deficit reduction even more to-the-bone spending cuts.

But Jim Horney, an economist at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities who analyzed the bill, has a message for Boehner: You’re wrong.

Horney’s argument gets pretty far into the fiscal policy weeds, but here’s the gist. For starters, eliminating those oil company subsidies and tax perks for corporate jets is a quick and easy way for the government to bring in more money and, as Horney points out, doing so “is clearly allowed under the proposed agreement.”

Next, to gauge how much you’ve trimmed the federal deficit, you’ve got to have a baseline from which to start. The GOP claims the debt ceiling bill’s supercommittee uses what’s called a “current-law” baseline; in plain English, a starting point in which the status quo reigns, in which laws governing Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and taxes remain untouched.

This matters because it puts Democrats seriously behind the 8-ball in demanding new revenues from the deficit supercommittee. Take the Bush tax cuts. The way the GOP sees it, their expiration at the end of 2012 would not be considered new revenue; after all, that’s what the law already says. Why is this important? Because in the search for new revenue, under the GOP’s rules, supercommittee members would be fighting an uphill battle to enact more tax increases on top of the Bush tax cuts’ expiration. In short, it becomes really, really hard for Democrats to demand a balanced proposal out of the supercommittee, setting us up another lopsided round of cuts. And that’s why, in the GOP’s words, a current-law baseline “effectively mak[es] it impossible for [the] Joint Committee to increase taxes.”

Wrong again, Horney argues. Nothing in the debt ceiling bill, he says, requires using a current-law baseline to measure deficit reduction and so blocking future revenue from tax increases. If the supercommittee’s members want to use a different starting point, one that takes into the account the deficit-cutting effects of tax reforms, they’re free to do so. “It is not the terms of the new agreement,” Horney writes, “but rather the opposition of Speaker Boehner (who has promised to appoint to the Joint Committee only members who will refuse to consider any revenue increases) and other Republican leaders, that threatens to prevent the Joint Committee from considering a balanced approach to deficit reduction.” And with the short-term mandates of the Budget Control Act centered entirely on spending cuts, the supercommittee is the only remaining opportunity for lawmakers to squeeze some balance into the deal.