Mac McClelland

Editors’ note: Mac is spending a month in her home state of Ohio, reporting on the Wisconsin-style showdown involving Republican Gov. John Kasich, public employees, unions, teachers, students, and struggling middle-class families.

It’s always something in Ohio. Last week, it became legal to bring concealed weapons into bars. A labor protest shut down a busy street in downtown Columbus. And the hotly contested, penny-pinching budget was signed into law by Gov. John Kasich.

For the friends I’ve been staying with, the impending budget has been wreaking havoc on domestic tranquility. First, Anthony got laid off because the budget was slated to cut so much from his employer, the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel. Then, the family got the news that the OCC cut wasn’t going to be quite as bad as anticipated. So now, though many of his coworkers are still out of a job, Anthony’s is safe. The concern has shifted mostly onto Erin, a public school teacher.

Here’s what’s troublesome for her in the budget: a requirement that schools receiving federal Race to the Top grants ditch their longstanding experience- and education-based pay system in favor of an alternative, like merit-based pay. Erin’s school is a Race to the Top school. While she signed on to her job with the impression that her future salary level would be guaranteed by a predetermined schedule, this provision means cash-strapped school administrators could decide that, based on some as-yet-to-be-determined criteria, her salary should be $10,000 or $20,000 less than it currently is. Normally, Erin’s union could likely prevent any arbitrary salary changes or advocate on her behalf. But the Ohio legislature recently passed Senate Bill 5, a Wisconsin-y anti-collective-bargaining law that will render her union effectively powerless.

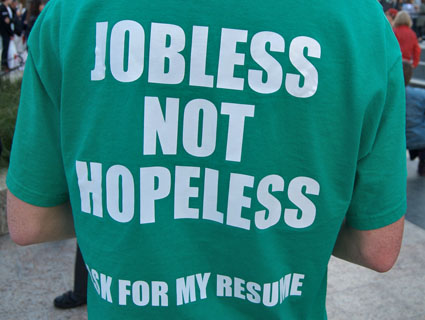

That was the subject of last week’s protest. Almost as soon as SB 5 passed, opponents started gathering signatures to get a repeal measure on the November ballot. Last Wednesday, huge crowds gathered in downtown Columbus to march to the secretary of state’s office and deliver those signatures. Shirts and flags identified them as firefighters, transit workers, teachers, electricians, bikers, state troopers; residents of Columbus, Cleveland, Findlay, Toledo; members of the SEIU, UAW, AFL-CIO. There was a professional drumline. There was the mayor, whom Erin nearly ran down with her unwieldy stroller when she veered toward him to shake his hand.

The organizers needed about 230,000 to get the SB 5 repeal on the ballot. They got 1,298,301. “We can’t guarantee anything,” said a spokeswoman for We Are Ohio, the campaign driving the effort, “but we’re confident with the amount of signatures we’ve collected that we have a lot of support on our side.”

Erin hopes they’re right. She’s nervous about it, though. So is Lindsey, another gal who lived in our dorm when we all went to Ohio State 10 years ago. Lindsey teaches middle-school English in rural Logan, about an hour outside Columbus. She stopped by for a visit the other day, bringing one of her kids, her two-month-old, to meet Erin’s eleven-month-old. Most of the talk that wasn’t about breast-feeding was about SB 5. Though Lindsey doesn’t teach at a Race to the Top school, under the new legislation her district can opt out of its established pay schedule. And with union protections in jeopardy, she’s not taking any chances.

“My husband wants to buy a new couch,” she said. But—she cocked her head and winced hard—she doesn’t want to take any money out of their savings until the repeal passes (or not) this fall. “We don’t know what’s gonna happen.”

Front page image by ProgressOhio/Flickr