Photo: Flickr/stolenbyme

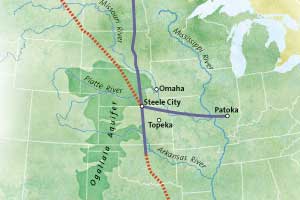

Environmental activists have long criticized the production of tar-sands oil; this especially dirty form of fuel demands tons of energy to obtain and results in high greenhouse gas emissions, not to mention the toxic wastelands its extraction leaves behind. But a new report, “Tar Sands Pipeline Safety Risks” (PDF), looks more closely at the environmental costs associated with the oil’s transportation—which might soon run straight down the middle of the continent. A proposed TransCanada pipeline, the Keystone XL, would carry billions of gallons of crude tar sands oil from Canada into the US. This raw oil—more corrosive, volatile, and acidic than the upgraded synthetic tar-sands oil we’ve become used to—would flow from Alberta to Houston, through some valuable wetlands and aquifers in the Midwest.

What worries the report’s contributors, including the NRDC and the Sierra Club, are the risks associated with pumping raw tar-sands oil through pipelines meant for more processed oil. Normally, the raw form of tar-sands oil (bitumen) goes through an upgrade and reaches the US as synthetic crude oil, a product similar to the conventional stuff. But more and more, refineries are skipping this upgrade process and sending their oil off as something referred to as DilBit, which could pose greater risks to pipeline integrity because it’s more corrosive, makes for nastier spills, and causes leaks that may be harder to detect. And the fact the Keystone XL would transport DilBit—up to 900,000 barrels a day through 1,600 miles of pipeline—means the center of the country would be especially vulnerable to a toxic spill of BP-like proportions.

A specific concern associated with DilBit is that one of its dilutents, a type of natural gas, can form bubbles that impede the flow of oil. This is known as “column separation,” and it presents many of the same signs as a leak would. The problem is, the cure for column separation is to pump more gas down the line. But if a leak were the real cause of the slowed gas, pumping more gas would be disastrous. Case in point: Last July, when a pipeline owned by Enbridge spilled a million gallons of crude oil into Michigan’s Kalamazoo River, an initial investigation revealed that Enbridge’s data had been misinterpreted as column separation rather than a leak. It took responders hours to get to the scene to start cleaning up the oil because of this mistake.

“That example shows that [DilBit] is very tricky to work with,” says Josh Mogerman, spokesperson for the NRDC. “There just haven’t been a lot of studies on what’s necessary to contain this stuff and really monitor it well.”

TransCanada promises that its safety technology is top-notch, its spill response time unbeatable. “Each year, billions of gallons of crude oil are safely transported on pipelines,” spokesman Cunha wrote in a November statement. “The vast majority of pipeline leaks are small, with most involving less than three barrels, 80 percent of spills involve less than 50 barrels, and less than 0.5 percent of spills total more than 10,000 barrels.” But Cunha’s attempts to assure the public arrived after a year that saw the Midwest’s worst oil spill in history, not to mention the not-so-distant BP catastrophe in the Gulf.

The Department of State will not issue a final decision on the project until later in 2011. In the meantime, environmental groups are trying to dissuade Obama from approving the project by launching an ad campaign against the pipeline, releasing reports about the pipeline’s dangers, keeping count of all spills associated with the Keystone project, and promoting awareness about the territory the Keystone XL would traverse. Among the locations it would cross through: the fragile Ogallala Aquifer, which provides a third of the nation’s irrigation water; the Platte River, a stopping point for the endangered Whooping Crane; and the Deep Fork Wildlife Area, home to Bald Eagles and bobcats, in Oklahoma.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Enbridge Spill released a million barrels of crude into the Kalamazoo River. It should have said a million gallons. We regret the error, and have since corrected it.