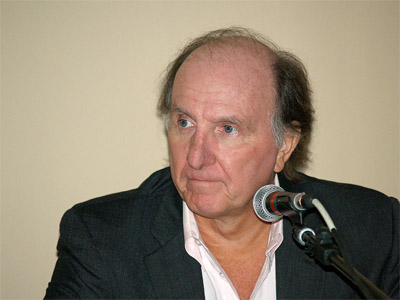

<a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wayne_Barrett_by_David_Shankbone.jpg">David Shankbone</a>/Wikimedia Commons

Spend a day working for Wayne Barrett, and you’ll get a taste of his great loves in life: punctuality, precision, Google Documents, and the word “fuck.”

Spend a semester with him, and he’ll develop an even deeper passion: you.

On Tuesday, Wayne—one of the last giants of political investigative reporting in New York City—offered an elegaic farewell to his readers at the Village Voice, where he’d raked the muck full-time since 1978—the year of my birth. Beleaguered by financial woes (as we all are), searching for a sound balance between costly longform reporting and cheap blog snark, the Voice can no longer afford Wayne. It loses longtime metro columnist Tom Robbins in the deal, too, because in a profession full of neurotics and back-stabbers, Tom is the most generous, empathetic guy you’ll find, from humoring an intern’s anti-Yankees trash talk, to running a license plate for a cub reporter, to donating a kidney to a friend, to “going out with the guy who brought me to the dance”—as he told Wayne when explaining why’d he quit the Voice, too.

Let’s not cry over these guys yet. Though the addresses may change, they’ll keep on transforming our weird world with wicked good writing. Tom’s honesty, lyrical prose, and insistence on keeping 10-year-old interview tapes once freed an ex-FBI agent dubiously accused of a mob murder. Wayne—well, among other things, you can thank Wayne for the fact that “President” and “Rudolph Giuliani” don’t go together in a sentence.

But now’s as good a time as any to reflect on Wayne’s reach, because it goes far beyond his own writing: He’s a one-man journalism school for aspiring copy-slingers, indirectly responsible for much of what you read in MoJo and the rest of the investigative world. He’s always leaned on a cadre of unpaid interns to assist with his research. Unpaid internships generally get a well-deserved bad rap: free labor, exploitation, insecurity. But if you worked for Barrett and paid him a hefty sum each day for the privilege, you’d still be making out like a greasy politician on the deal. From Politico to Rolling Stone to here and here and here at MoJo and far beyond, hundreds of Wayneniks are out there, and we pretty much all feel the same way: His guidance humbled us and empowered us. It made us better reporters and people.

To politicians, pundits, and civil servants, Wayne is a journalistic Marine Corps: no greater friend, no worse enemy. And he runs his charges, too, with military discipline. Perhaps that’s why I took such a shining to him. Good St. Joe’s kid that he was, he’d considered becoming a man of the cloth before Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism shanghaied him into an equally mysterious priesthood. I’d taken a similar route to the J-school, getting lost on the way and stopping for a couple of years in the military. As a result, we both attacked our journalistic subjects with the zeal—and, occasionally, the rage—of the pious ideologue.

What I lacked, and what he imparted to me, was a rigorous devotion to living for the details. Like my first day on the job, when, not knowing what time to report to his office, I rolled in after 9:30. Wayne was out reporting in the field somewhere, and at his desk sat my new cohort, four other interns, dutifully taking notes as the man dictated their assignments, his voice a gentle but ardent in the speakerphone. He paused for a moment, hearing the ruffle of pages in my steno pad as I settled into a chair. “Is Adam there?” I responded. “Can you take me off the speaker for a second?” I picked up the receiver.

A blast of volume nailed me like a sharp No. 2 pencil in my inner ear. “Where the FUCK are you COMING from? I don’t know WHAT the FUCK newsroom you’ve worked in. Do they start whenever the fuck they want in the morning? This is BULLSHIT, Adam. Look, if you don’t want to do this thing, if it’s not compatible with your schedule or wake-up time or whatever the fuck—”

Somehow, it got smoothed over, and I learned what no drill instructor managed to get through to me. I learned what a total commitment should feel like.

Once they get a feel for how much (or how little) their readers can digest, professional journalists feel temptation to skimp on the legwork, to compensate for a paucity of facts with an excess of emotion. It’s a temptation I’ve succumbed to on occasion, especially in our bloggy New New New Journalism world. But if you show Wayne a facility for resisting that temptation—for tempering your fervor with cold, hard, indisputable details no one else bothered to unearth—he’ll walk through fires (or set a couple of them) on your behalf.

When he works away from the newsroom, you and your fellow aspirants compile your labors each night for him in a shared Google Doc: hundreds of daily pages of clips from Lexis Nexis and the Voice’s crusty morgue full of browning back issues; interview notes; sidebar suggestions; no-go phone calls; random insights. At first, he’ll take it all and weave it into an epic cover story himself. The next month, he’ll run it past you to copy edit and fact check. Later, he’ll trust you to help him with structure and story points. Then, maybe he leans on your reporting and writing and gives you a double byline. At some point, looking at your work, he says, “Hey, this is good. You should write this as a piece of your own…”

And you do. And maybe he takes you along to interview a government official or TV personality, and you learn how to overcome your starstruck-ness, how to turn a half-hour interview into a five-hour marathon, how to slip the hard questions in, how to (politely) induce in your interviewee a state of total honesty through total exhaustion.

Maybe he introduces you to every major politician and beat reporter at a Super Tuesday shindig, cajoles editors into calling for your resume and clips, buys you a beer, asks about your fiancee and when you guys are gonna get around to having a couple of bambinos. Fran and the kids are everything to him, after all.

By this point, you realize you’re one of those kids. Not blood, but pretty damn near.

Tuesday afternoon, the day he calls it quits at 36 Cooper Square, I reach Wayne on the phone, and he ‘s as happy as I’ve ever heard him. “I’m not concerned about the Voice,” he tells me. “I’m concerned about the beat.”

I’m worried about neither. The Voice is still in capable editorial hands. Wayne has his health, his family, and a new office at The Nation Institute. Also, a new set of politicians in Albany and the five boroughs to antagonize. His salary won’t be as high, and “I won’t have as much space as I’ve been able to have,” he says.

But he tells me there’s one big perk, and it seems to make all the difference: “They say I can bring interns!”