Photo: Mark Murrmann

Editors’ Note: This education dispatch is part of a new ongoing series reported from Mission High School, where youth issues writer Kristina Rizga is known to students as “Miss K.” Click here to see all of MoJo’s recent education coverage, or follow The Miss K Files on Twitter.

There’s a cold rain falling in San Francisco the night of Mission High School‘s annual open house, and principal Eric Guthertz is chagrined by the low turnout. Iron chandeliers illuminate his face as he stands near the public school’s Spanish Baroque-styled entrance. “Welcome!” he says brightly as one prospective family signs in at a greeting table laden with veggies, cookies, and cups of juice. Like many Mission families, this one doesn’t speak English, so a Spanish interpreter explains to the parents that she’ll be translating Guthertz’s talk this evening. The school’s parent liasion, Benita Varnado, hands the young mother a small receiver with headphones, while a student volunteer fixes up a plate of cookies for the dad. We all move into the auditorium and wait for the Q&A to begin.

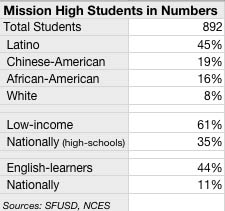

Until recently, Mission High had a pretty bad reputation. This is the place you sometimes landed after being expelled from other schools in the city; some locals still refer to it as a “dumping ground.” But in 2009, things started to change in dramatic, visible ways. Dropout rates fell from 32 percent to 8 percent in one year. Test scores shot up. College acceptance rates grew. That’s pretty impressive no matter where you are—and practically miraculous in near-bankrupt California, which ranks 47th in the nation [PDF] in terms of school funding per student. Given that nearly half the students here were raised with a first language other than English, and 61 percent are considered poor, it’s pretty clear that Guthertz and his colleagues are doing something right. So what is it? And how can other public schools learn from this tiny microcosm, which so neatly demonstrates the nation’s inner-city education woes?

It turns out that these are not the questions on parents’ minds at tonight’s open house.

“Do kids go off campus for lunch?” asks a 34-year-old Latina mom, her 14-year-old son in tow. Only seniors, says Guthertz, and they can lose that privilege if they miss classes after lunch. And if they miss classes before lunch? Linda Jordan, the school’s family community outreach liasion, will call their parents. She’ll even call some kids preemptively, telling them to get out of bed and head to school.

“What is the atmosphere for critical and joyful learning?” asks a Mission hipster mom with short, spiky blond hair. Guthertz rattles off the many ways in which the school goes beyond filling out bubbles: Individual student portfolios that include essays, poems, research papers, and art projects.

“What about class size?”

“We have 890 students, but our classes are small, ranging between 16-28 students,” says Guthertz. Each student gets a teacher advisor; together they work on everything from the student’s “post-secondary success plan” to resolving everyday school and family challenges. Teachers don’t work in isolation, either; shared planning sessions are the norm. The word “holistic” gets used.

Michelle, a Chinese-American sophomore, steps up on stage and introduces her Chinese immigrant parents. She translates for her mom, who remarks that Michelle is their third child at Mission High. “My oldest kid is at Stanford, and the middle one at the Art Institute,” Michelle’s mom tells the parents. “They have really good teachers here, different sports, languages. And children really learn how to communicate with different people from all over the world.” Mission High’s website can even be translated into 12 languages.

Guthertz mentions how important it is to help students of color see connections between their personal lives and at least some of the material they’re learning. “We teach Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn,” he says. “But we also read Amy Tan and Maya Angelou.” A blonde mother with black cat-eye glasses asks how teachers deal with the students who have the highest grades. “Do you do tracking?” she asks, referring to the widely used method of separating students by achievement level.

Guthertz mentions how important it is to help students of color see connections between their personal lives and at least some of the material they’re learning. “We teach Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn,” he says. “But we also read Amy Tan and Maya Angelou.” A blonde mother with black cat-eye glasses asks how teachers deal with the students who have the highest grades. “Do you do tracking?” she asks, referring to the widely used method of separating students by achievement level.

“We don’t believe in tracking,” Guthertz says. But because classes are small, there are ways in which teachers can “push things a little harder with higher-achieving students.”

“How long is the school day?” a teenager asks. The audience bursts into laughter. Soon after, the open house adjourns.

I catch up with the young Latina mom and her son to see what they think of Mission High so far. The prospective student is noncommittal. “I want to become an engineer one day,” he says. “All I care about is which school will help me do that.” His mom seems more impressed. “It’s great that Mission has a person like Linda Jordan who gets into kids’ business,” she says. “I want them to pay attention to my kid.” The two speed off into the night.