Osvaldru/istockphoto.com

[Editor’s Note: Click here to see a related slideshow of tea party signs.]

IN A WIDELY READ essay about the tea party movement published earlier this year in the New York Review of Books, historian Mark Lilla provided a now-familiar explanation about what motivates the tea partiers. They are, he reckoned, angry about the recession; angry about health care reform; angry about President Obama; and angry about educated elites forever telling them what to do. “A new strain of populism is metastasizing before our eyes,” he said, and he described the movement this way:

It supports with worshipful intensity the Constitution of the United States; it places itself on the side of the individual and of liberty in opposition to an encroaching government bureaucracy; it respects the judgment of the founding fathers who had so wisely incorporated the separation of federal powers and the rights of the states into the great national document; it defends the American right to enjoy the sweat of one’s own labor and the rewards of one’s ability.

Actually, Lilla didn’t write that last bit. Another historian did. This passage comes from Frederick Rudolph, writing in 1950 about the American Liberty League, a group formed in 1934 in reaction to FDR’s New Deal. But it sounds pretty familiar, doesn’t it? All I did was change the verbs to the present tense, and it might as well have come from a portrait of the tea party written the day before yesterday.

And that’s a problem. It’s a problem because too many observers mistakenly react to the tea party as if it’s brand new, an organic and spontaneous response to something unique in the current political climate. But it’s not. It’s not a response to the recession or to health care reform or to some kind of spectacular new liberal overreach. It’s what happens whenever a Democrat takes over the White House. When FDR was in office in the 1930s, conservative zealotry coalesced in the Liberty League. When JFK won the presidency in the ’60s, the John Birch Society flourished. When Bill Clinton ended the Reagan Revolution in the ’90s, talk radio erupted with the conspiracy theories of the Arkansas Project. And today, with Barack Obama in the Oval Office, it’s the tea party’s turn.

There are, of course, differences between each of these movements. The Birchers were single-mindedly obsessed with communist infiltration, a fear that’s largely gone out of style; the Arkansas Project crowd seemed motivated more by cultural issues and a burning personal hatred of the Clintons than by policy matters. And there are structural differences, too. The Liberty League and the John Birch Society were formal groups with formal leadership. The anti-Clinton brigade was chaotic and leaderless. And the tea party movement is somewhere in between: funded and inspired partly by formal organizations (FreedomWorks, the Tea Party Patriots) and specific personalities (Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck), but with a membership that, in practice, is an agglomeration of hundreds of local groups that often compete with each other and hotly insist that they take direction from no one.

But these differences are superficial. The similarities are far more telling, and the place they start is a shared preoccupation with the Constitution. The Liberty Leaguers, as Rudolph wrote, spoke of it with “worshipful intensity.” The John Birch Society—which is enjoying a renaissance of sorts today—says of itself, “From its earliest days the John Birch Society has emphasized the importance of the Constitution for securing our freedom.” And as Stephanie Mencimer reported in our May/June issue “One Nation Under Beck“), study groups dedicated to the Constitution have mushroomed among tea partiers. [CLICK HERE TO READ MOJO’S STORY ABOUT TEA PARTY STUDY GROUPS.]

Other shared tropes include a fear of “losing the country we grew up in,” an obsession with “parasites” who are leeching off of hardworking Americans, and—even though they’ve always received copious assistance from business interests and political operatives—a myth that the movement is composed entirely of fed-up grassroots amateurs. Take, for example, this description of Pam Stout, the star of a seminal tea party profile written earlier this year by David Barstow of the New York Times. After Obama took office, he writes, “Mrs. Stout said she awoke to see Washington as a threat, a place where crisis is manipulated—even manufactured—by both parties to grab power. She was happily retired, and had never been active politically. But last April, she went to her first tea party rally.” Compare that to the description of Estrid Kielsmeier in Suburban Warriors, Lisa McGirr’s history of ’60s-era right-wing activism in Orange County, California. Kielsmeier, a resident of my hometown of Garden Grove (my mother acidly recalls PTA meetings at my elementary school as hotbeds of John Birch Society activism), was a homemaker who ran the local gubernatorial primary campaign headquarters of ultraconservative oilman Joe Shell against Richard Nixon in 1962: “Her baby played in a playpen next to her desk while Kielsmeier participated in what she later called her first real involvement in politics. ‘Up to that time…it was education and just kind of…networking, really.'”

Above all, though, is the recurring theme of creeping socialism and a federal government that’s destroying our freedoms. In the ’30s this took the form of rabid opposition to FDR’s alphabet soup of new regulatory agencies. In the ’60s it was John Birch Society founder Robert Welch’s insistence that the threat of communism actually took second place to the “cancer of collectivism.” Welch believed that overweening government had destroyed civilizations from Babylonia to 19th-century Europe, and he said his fight could be expressed in just five words: “Less government and more responsibility.”

Three decades later, Newt Gingrich rode into the speaker’s office on the Contract with America’s small government promises and promptly shut down Washington in a fight with Clinton that mostly revolved around conservative desires to slash a laundry list of social programs. And today, tea party rhetoric is shot through with charges both that the president is a closet Marxist (“Obama isn’t a US socialist,” thundered Fox News commentator, Steven Milloy at a tea party convention earlier this year, “he’s an international socialist!”) and that the federal government has become a multitentacled monster that needs to be crushed before it enslaves us all. In an interview with the Columbia Journalism Review, the Times‘ Barstow diagnosed the “idea of impending tyranny” as the tea partiers’ deepest and most abiding nightmare: “I was struck by the number of people who had come to the point where they were literally in fear of whether or not the United States of America would continue to be a free country.”

Finally, there’s the weaving, kaleidoscopic thread that binds these groups together: their insatiable appetite for conspiracy theories. Robert Welch—in addition to his famous belief that water fluoridation was a communist plot—believed a shadowy group of “insiders” ran the world, stretching back to the founding of the Illuminati in 1776 and continuing through the French Revolution and The Communist Manifesto, and on to the UN, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Trilateral Commission. In like fashion, the anti-Clinton zealots developed a colorful and ever-growing bestiary of shadowy plots. They believed, among other things, that Clinton had Vince Foster murdered; that he conducted a drug-running operation out of Mena airfield in Arkansas; that he’d fathered a black child out of wedlock; and that he had allowed dozens of

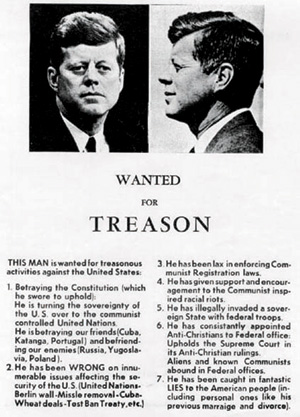

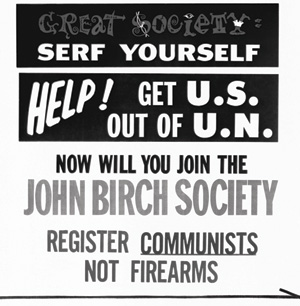

Finally, there’s the weaving, kaleidoscopic thread that binds these groups together: their insatiable appetite for conspiracy theories. Robert Welch—in addition to his famous belief that water fluoridation was a communist plot—believed a shadowy group of “insiders” ran the world, stretching back to the founding of the Illuminati in 1776 and continuing through the French Revolution and The Communist Manifesto, and on to the UN, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Trilateral Commission. In like fashion, the anti-Clinton zealots developed a colorful and ever-growing bestiary of shadowy plots. They believed, among other things, that Clinton had Vince Foster murdered; that he conducted a drug-running operation out of Mena airfield in Arkansas; that he’d fathered a black child out of wedlock; and that he had allowed dozens of  big-time donors to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. John Birch Society fliers like these circulated in Dallas before the JFK assassination. Richard Mellon Scaife, the primary funder of the Arkansas Project, called Foster’s death “the Rosetta Stone to the Clinton administration” and told George magazine, “Listen, he can order people done away with at his will…God, there must be 60 people who have died mysteriously.”

big-time donors to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. John Birch Society fliers like these circulated in Dallas before the JFK assassination. Richard Mellon Scaife, the primary funder of the Arkansas Project, called Foster’s death “the Rosetta Stone to the Clinton administration” and told George magazine, “Listen, he can order people done away with at his will…God, there must be 60 people who have died mysteriously.”

Today’s conspiracy theories are different in detail but no less wacky—and no less widespread. Some 30 percent (PDF) of self-identified tea partiers believe that Obama isn’t a natural-born citizen, according to an April New York Times poll. Some tea partiers are worried about internment camps for conservatives, an echo of a theory peddled by the Birchers in the ’60s. As Canadian conservative Jonathan Kay bemusedly wrote in Newsweek after attending a tea party convention last winter, Jeremiah Wright and Bill Ayers are also frequent obsessions, “the idea being that they were the real brains behind this presidency, and Obama himself was simply some sort of manchurian candidate.” And of course there’s ACORN, the centerpiece of a baroque theory in which the now-defunct organization ran the Democratic Party, forced banks to make loans to minorities and poor people via the Carter-era Community Reinvestment Act, crashed the economy, and got Obama elected president. Robert Welch would be proud.

Ideology and paranoias aside, there are also more concrete connections between the generations. Some are unsurprising. Industrialist Fred Koch, for example, was one of the early supporters of the John Birch Society. His son, David Koch, helped launch Citizens for a Sound Economy, which later split into two organizations, FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, both of which are major funders and organizers of the tea party movement.

Other links are almost charming: One of the most popular tracts among Birchers in the ’60s was W. Cleon Skousen’s The Naked Communist; 50 years later, Skousen has been rediscovered by Glenn Beck, who relentlessly hawks Skousen’s 1981 book, The 5000 Year Leap. And still others are simply bizarre: Welch was convinced that the 17th Amendment, which affirms the direct election of senators, represented a poisonous concentration of power in the federal government. Today this obscure fixation has made a comeback among the tea partiers.

All of this points in one direction. The growth of the tea party movement isn’t really due to the recession (in fact, polling evidence shows that tea partiers are generally better off and less affected by the recession than the population at large). It’s not because Obama is black (white Democratic presidents got largely the same treatment). And it’s not because Obama bailed out General Motors (so did George W. Bush). It’s simpler. Ever since the 1930s, something very much like the tea party movement has fluoresced every time a Democrat wins the presidency, and the nature of the fluorescence always follows many of the same broad contours: a reverence for the Constitution, a supposedly spontaneous uprising of formerly nonpolitical middle-class activists, a preoccupation with socialism and the expanding tyranny of big government, a bitterness toward an underclass viewed as unwilling to work, and a weakness for outlandish conspiracy theories.

Is this good news or bad? Some of both, I think. Let’s start with the worst news: These right-wing fluorescences are, unfortunately, getting more potent over time as they learn from their mistakes. Raw numbers tell part of the story. The Liberty League topped out at about 75,000 members, and even that number may have been exaggerated. They simply weren’t good enough at concealing the fact that they were little more than a group founded by rich industrialists who disliked the government interfering with their business. The Birchers did better, attracting support from 5 percent of the population and claiming a core membership of more than 100,000.

The anti-Clinton forces did better still, boasting a following of millions, though there was no formal organization to compare to the Liberty League or the John Birch Society. And the tea party has done even better: An April New York Times poll suggests not only that the movement attracts support from 18 percent of the population, but that as many as 5 million people have attended tea party rallies and perhaps a million core supporters have donated money to a tea party group.

Beyond sheer numbers, though, right-wing extremist groups are also becoming more effective. The Liberty League withered after it failed to make even a dent in FDR’s 1936 reelection campaign. The Birchers improved on that record, winning lots of local campaigns and eventually helping Barry Goldwater win the Republican presidential nomination in 1964, before collapsing under the weight of Robert Welch’s increasingly bizarre rants. The ’90s activists were more successful yet, helping Gingrich take over Congress in 1994, impeaching a president in 1998, and eventually sending George W. Bush to the White House.

And the tea partiers? Their history hasn’t been written yet, but they have, for all practical purposes, already trumped every previous generation of activists by successfully taking over the Republican Party almost entirely. And this is, at last, something that really is new: The Liberty League was rejected by the GOP almost from the start, the Birchers were all but spent as a political force after the 1964 election debacle, and even during the ’90s there were still moderate factions in the GOP. But today, there’s virtually no one left in the party leadership who doesn’t at least claim to adhere to tea party principles. Recent polls by both Gallup and the Mellman Group (PDF) find that the views of self-identified tea party supporters are nearly identical to the views of self-identified Republicans across the board. Gallup’s analysis may go a little too far in saying that the tea party movement is “more a rebranding of core Republicanism than a new or distinct entity on the American political scene,” but not by much.

How did this happen? Partly it’s a reflection of the long-term rightward shift of the Republican Party. Partly it’s a product of the modern media environment: The Birchers were limited to mimeograph machines and PTA meetings to get the word out, while the tea partiers can rely on Fox News and Facebook. Beyond that, though, it’s also a reflection of the mainstreaming of extremism. In 1961, Time exposed the John Birch Society to a national audience and condemned it as a “tiresome, comic-opera joke”; in 2009, it splashed Glenn Beck on the cover and called him “tireless, funny, self-deprecating…a gifted storyteller.” And it’s the same story in the political community: The Birchers were eventually drummed out of the conservative movement, but the tea partiers are almost universally welcomed today. “In the ’60s,” says Rick Perlstein, a historian of the American right, “you had someone like William F. Buckley pushing back against the Birchers. Today, when David Frum tries to play the same role, he’s completely ostracized. There are just no countervailing forces in the Republican Party anymore.” Unlike the Birchers, or even the Clinton conspiracy theorists, the tea partiers aren’t a fringe part of the conservative movement. They are the conservative movement.

So where’s the good news? Part of it is that the movement’s 15 minutes could be nearly up. The tea partiers may have expanded faster than the Birchers thanks to Fox News and talk radio, but the same media echo chamber that enabled this has also shortened attention spans and provided 500 channels of competition for the Glenn Becks of the world. The speed of the tea partiers’ rise may foreshadow an equally fast decline as their act begins to grow stale.

Likewise, the sheer size of the tea party movement may be as much a curse as a blessing. An insurgent movement can retain its vigor if it remains limited to true believers, but once it takes the reins of power, it has no choice but to offer a winning platform if it wants to keep its influence. The tea partiers are thus likely to be victims of their own success: When everyone’s a tea partier, then no one’s a tea partier. Right-wing extremism may win majorities in Arizona and a few other basket-case states, but it doesn’t win national elections, which means the tea partiers will either move to the center or die.

In fact, there’s already evidence that this is happening. There are only a handful of genuine tea party candidates running in November—folks like Nikki Haley in South Carolina, Sharron Angle in Nevada, and Rand Paul in Kentucky—and plenty of evidence that tea party affiliation might not help them much. Tea party favorite Doug Hoffman, for example, accomplished nothing in New York’s 23rd congressional district last year except splitting the GOP vote and handing the district to a Democrat for the first time since the Civil War. And tea party darling Scott Brown, who came from behind to win Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat earlier this year in Massachusetts, has turned out to be a pretty moderate Republican. The tea partiers, it turns out, love these candidates for taking on the establishment—not necessarily for being able to win, or even (in Brown’s case) for toeing the purist anti-tyranny party line.

The tea party movement is likely to provide plenty of drama this November, but if the historical record is anything to go by, it won’t last long after that. As with the earlier incarnations, its core identity will slowly fade away and become grist for CNN retrospectives, while its broader identity becomes subsumed by a Republican Party that’s been headed down the path of ever less-tolerant conservatism for decades. In that sense, the tea party movement is merely an unusually flamboyant symptom of an illness that’s been breeding for a long time.