Photo of North Korean nuclear negotiators fishing off Sandy Hook, NJ, courtesy of Kurt Pitzer.

Read Part II: Hamburger Diplomacy.

Author’s Note: When I first met Bobby Egan at his restaurant in Hackensack, New Jersey, he set a plate of barbecue in front of me, sat down, and launched into the most unbelievable story I’d ever heard. For 13 years, Egan claimed, he had inserted himself into a dangerous, high-stakes political game between Washington and Pyongyang. I shook my head when he told me—among other mind-boggling tales—about how he submitted to a truth-serum interrogation on his first trip to Pyongyang, collected North Korean hair samples for the FBI, and became fishing buddies with North Korea’s head of American affairs, Han Song Ryol.

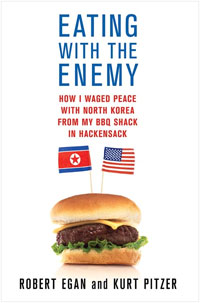

Turns out the stories were true. In the early 1990s, after the North Koreans’ efforts to reach out to Washington were rebuffed, they turned to Egan, a high-school dropout from a mobbed-up Jersey town who had worked with Vietnamese officials as a POW activist. Egan’s wild yarns are retold in our new book, Eating with the Enemy: How I Waged Peace with North Korea from My BBQ Shack in Hackensack, out this week from St. Martin’s Press. The following excerpt, told in Bobby’s voice, picks up in 2002, shortly after President Bush declared North Korea part of an “axis of evil.”

—–

“INFECTED GUMS,” HAN SAID. He winced as he pulled his lip up and his cheek out. His front teeth looked like an old graveyard. I looked deeper. The flesh around his molars was violet-colored and swollen. “Nothing they can do,” he said. “Too much money.”

It was bad for world peace to have North Korea’s ambassador in terrible pain. And I couldn’t stand to see my buddy suffer.

“We’ll fix it,” I said. “I’ve got just the guy.”

John “The Greek” Kallis was the best oral surgeon in northern New Jersey. He once pulled a wisdom tooth for Tom Cruise, and the photos in his office showed the other famous mouths he’d worked on: Kevin Bacon, Jennifer Lopez, Patrick Ewing of the Knicks, Doug Gilmore of the New Jersey Devils, ice skaters Silvia Fontana and John Zimmerman, and cast members from The Sopranos.

More importantly, The Greek was a friend of mine. He was a street guy like me—born to a couple of immigrants in Hell’s Kitchen and raised in a tough neighborhood of Fort Lee, N.J., which was important because I needed somebody willing to take a few risks who wouldn’t ask too many questions.

I told The Greek that the North Korean in charge of handling the nuclear crisis had a bad toothache, and that easing his pain was crucial to the stability of the world. He agreed right away to help. And he took it on faith when I said we’d try to get funds from a charity group to pay his bill.

I told The Greek that the North Korean in charge of handling the nuclear crisis had a bad toothache, and that easing his pain was crucial to the stability of the world. He agreed right away to help. And he took it on faith when I said we’d try to get funds from a charity group to pay his bill.

I told him the FBI knew I was organizing dental work for Han, which was true, although my contact, Special Agent Tom Marakovits, had tried to chase me off the idea. “Dentistry can be dangerous,” he’d said as we discussed the idea at Cubby’s. “What if something bad happens, God forbid. Or what if he alleges malpractice? We’re at war with these guys.”

“What if his infection gets worse, and he dies, because we don’t give him access to healthcare?”

“Don’t say that!”

“You’re right. God forbid.”

Marakovits shifted in his seat. “I checked into it, anyway. We’re not responsible for him.”

“You mean legally,” I said.

“If he is ill, he needs to return to his place of origin.”

I gave Marakovits a look. “You’ve never seen a medical facility in North Korea. If you had, you wouldn’t say that.”

“I’m looking out for your best interests,” he said. “You don’t have to take unnecessary risks.”

I took a long pull of my coffee. “Sure I do.”

“What do you mean, you do?”

“If we only took necessary risks, we wouldn’t get very far,” I said.

“You realize that if you get in trouble, I get in trouble.”

“Then I guess that makes us partners,” I smiled.

“Think about your family.” Marakovits glanced at the kitchen door. “If something happens to you, it will be bad for them, too.”

“Now you sound like a North Korean.”

He waggled his head back and forth. “If something goes haywire, bigger feet are going to step in from the Bureau,” he said. “I won’t be able to help you.”

I liked Marakovits. I did. Deep inside, part of him probably wanted to be doing what I was doing, mixing it up with the enemy. But he was timid. He had a badge and a cheap suit and a pension to protect. “We’re just going to knock him out, pull out a tooth or two.” I said. “When you see somebody in pain, don’t you want to help them?”

Marakovits sat upright. “Tell me you’re not going put the ambassador from North Korea under general anesthesia.” He clasped his hands on the table and fiddled with his thumb.

“Who’s the dentist? Does he have a license?”

“It’s better if you don’t know,” I said.

I walked Marakovits to his car and lied to him. I said I’d call before we did any dental work on Han.

The Greek cleared his calendar for the second Saturday in November, when his practice would normally have been closed. I arranged for Han to meet me at 8 a.m. on a side street nearby, where we could make sure neither of us had been followed by anybody from the Bureau. The less the FBI knew about it, the better. Han came with two guys—a security goon and one of his assistants—in a Chrysler sedan they used when they wanted to travel incognito. I came with Mike “O’D” O’Donovan, an old hunting buddy, who was ex-Special Forces and had just come back from showing coffee finca owners in El Salvador how to protect their land. With crew-cut gray hair, crazy-looking blue eyes and questionable table manners—he liked to gross out my daughters by eating live worms—O’D was not exactly what you’d call refined company. But he was one of the best private security men in the business, and it seemed like a good idea to have somebody who was loosely associated with the law in case anything went wrong.

The dentist’s office was on the ground floor of a beautiful residential tower next to the George Washington Bridge, with a view of Manhattan across the Hudson. We parked in the alleyway beside the building to avoid the surveillance cameras in the garage and left Han’s junior colleague with the cars.

An assistant took X-rays of Han’s jaw, and while we waited for the results, Han checked out at a framed photo of James Gandolfini sitting at a dinner table with a napkin, a bowl of pasta and a glass of wine in front of him. “The Greek worked on Tony Soprano?” Han asked.

I could tell he was nervous, so I went over and put my hand on his shoulder. “He’s the best of the best.”

The North Korean security goon sat in a lounge chair in the waiting room, where he stayed for the rest of the day. O’D positioned himself against the opposite wall. They put on sunglasses and pretended to ignore each other.

The Greek called Han and me back into his office. “This is the Panorex,” he said as a technician pinned Han’s X-ray onto a light box. We leaned in for a better look. “The immediate situation is the infection around this lower-left premolar, which has to come out right away,” he said. “The larger issue is you’ve got problems brewing in all four quadrants. There is some really primitive dentistry. These could flare up at any point.”

Later, when Han was under general anesthesia, The Greek told me he’d never seen anything like it. “Did you get a look at those bridges?” he said. “They’re aluminum. Hollow. Crimped on. They used to be called ash-can bridges. You hear about these things in school, but nobody’s done this kind of work since the 1940s.”

We agreed to remove six teeth and replace them with implants. “I’ll do this in stages,” he told Han. “It’s safer. We can do some today, and then in the next month or so—”

“No,” Han said. “All at once.” He worried that if war broke out, he could be recalled to Pyongyang with his mouth only partly fixed.

The Greek warned that putting him under anesthesia for most of the day would increase the risk of cardiac or respiratory problems. But Han insisted, and a technician hooked him to an IV drip and a machine to monitor his vital signs.

“I want Bobby to be in the room the whole time,” Han said.

Two dental assistants came in and prepped. O’Donovan followed them in, to observe. As The Greek sedated him, Han gripped my hand and then relaxed as he slipped into unconsciousness. O’D watched with a mixture of curiosity and disgust.

“You guys want to be heroes?” he said with a cynical grin. “Don’t knock him out. Knock him off.”

The dental assistants exchanged a look. O’D seemed too excited about the idea of blood and bone being chiseled out of an enemy ambassador. But he was just expressing how a lot of Americans felt after 9/11—looking for black and white, good and bad. Anybody from an enemy country was an enemy. Everything was simpler that way.

The Greek and his assistants went in hard with the drill, and soon the room filled with the sound of metal chipping against bone and the acrid smell of tooth enamel vaporizing into dust and smoke. Other times it sounded like they were sawing through wood. One of the assistants pumped steroids and antibiotics into Han’s veins to ward off swelling and infection. The Greek’s gloves were spattered red. The second assistant siphoned off the blood and spit pooling in Han’s mouth. Another served up a series of tools that looked like torture instruments. I’ve gutted plenty of animals with my own knife and seen some gruesome stuff in my time, but nothing quite like what they did to Han’s jaw that afternoon. I was proud of him for what he endured. I don’t care if he was unconscious, it was brave.

They flapped back his gums, yanked out the teeth and set them in a metal tray. The Greek cut a window in the upper jawbone, lifted the membrane that covered Han’s sinuses and then packed in pieces of bone so that new bone could take root.

The hours of surgery wore on. Outside the window the autumn sky was a clear slate. I thought of my first trip to Manhattan as a kid, and all the flags. They hung from tall poles, high out of reach, rustled by the wind here and there but mostly just limp pieces of green, blue, red and yellow. Behind them, the mirrored windows of the UN building reflected the bright sky and the dark city below. Our chaperones led us off the school bus into the General Assembly hall. We stood on an observation deck and stared at the strange-looking people: Africans wearing full-length robes, the Asian guys in business suits. I had some exposure to blacks and Hispanics. I’d seen a few in Fairfield and on TV. Dad warned me to stay away from them if they were in groups. But the UN was like landing on another planet. A caramel-colored man with a face like a wedge shook hands with a round-headed guy with gold-rimmed glasses and a little goatee. Flat faces and long faces huddled together. One wore a white headdress with a black ring around his forehead. What were these people called?

Our teachers made us eighth graders take turns listening to the General Assembly with a pair of headphones. Most kids listened for a few seconds and passed them on. I went last, and when I put the headphones on my ears, I couldn’t understand a word. One of the kids before me had switched the dial. I sat at the little desk, turned the knob and heard translations in French, Russian, Spanish, Chinese and Arabic. I didn’t know what the sounds were supposed to be. Where I came from, there was English, the northern New Jersey variety, and that was it. To us, kids from 15 miles south in Hoboken talked funny. I couldn’t stop turning the knob back and forth. One voice sounded like bubbles. Another sounded like knives. The world was full of people who understood what these noises meant. But I’d never know, and it made me feel small. I tried to imagine all these people, who were loyal to their own flags and their own languages, far beyond Fairfield and Roseland and Hackensack.

“Bolus!” The Greek shouted at one of his assistants. He was starting to sweat. He glanced up at the monitor, barking at his assistants in code words. “Titrate!” he yelled.

“What’s wrong?” I moved in closer.

“Arrhythmia. We gave him Atropine to dry out his mouth, but it’s making his heart beat differently.”

“Is that dangerous?” I tried to make sense of the lines blipping around on the monitor, as the anesthesiologist dumped more drugs into the IV. Han’s mouth gaped open. He looked like a vulnerable child. Across the room, O’D waved at me, put two fingers up to his lips and then mouthed the words, “Going out for a smoke.”

The Greek and his team kept picking away inside Han’s mouth. I took that as a good sign. Then all of a sudden, they shuffled around. “He’s stopped breathing,” one of the assistants whispered.

To be continued…

Part II: “Hamburger Diplomacy.” “An agent from Pyongyang, somebody like Cranky, would knock on my front door and rub out my whole family. And then he’d come after The Greek’s…Then a worse scenario occurred to me: What if Han died, and it led to war?”