Photo courtesy <a href="http://www.justice.gov/usao/mn/petters/petters_trial_exhibits.html">Department of Justice</a>

William Kovacs, the US Chamber of Commerce’s vice president of environment, technology and regulatory affairs, last year famously called for a “Scopes monkey trial of the 21st century” on climate change. Kovacs was referencing the lightning-rod 1925 court case that made it illegal to teach anything other than divine creation in Tennessee public schools—and he wanted a similar public hearing in which climate science would be put on the stand. The remark drew plenty of bad press, and Kovacs soon recanted his “inappropriate” analogy. But it looks like the chamber is angling for that monkey trial after all, by way of a lawsuit it’s filed against the Environmental Protection Agency that could be the first wave of a big-business assault on greenhouse gas regulations.

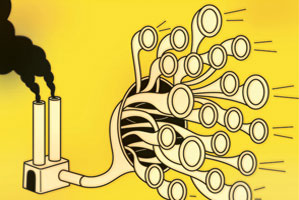

At issue is a scientific finding issued by the EPA last year concluding that greenhouse gases are a threat to human health, due to the lower air quality, extreme weather events, and heat waves caused by rising temperatures. The chamber announced its intent to sue the EPA last month in an attempt to have the endangerment finding, as it’s known, tossed out. The big-business lobby has been joined by a collection of trade groups like the American Farm Bureau Federation, the American Petroleum Institute, the National Association of Manufacturers, and the National Mining Association; free-market think tanks such as FreedomWorks and the Competitive Enterprise Institute; and the attorneys general of Texas, Alabama, and Virginia.

Legally, the chamber and its allies don’t have much of a case. In the 2007 case Massachusetts v. EPA, the Supreme Court found that greenhouse gases could be covered under the Clean Air Act if they are determined to threaten human health. Their ruling required the EPA to investigate whether carbon emissions did in fact pose a health risk. After the agency’s scientists reached that conclusion, the EPA was automatically required to regulate the sources of greenhouse gases—otherwise the agency would be breaking the law. And because the EPA’s directive is based on a scientific assessment, not a policy preference, it will be extremely hard to overturn, said Michael Gerrard, director of the Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School. “These petitions are a real long-shot,” he said. “The appellate courts tend to give a large degree of deference to the technical judgments of expert agencies, especially when they are based like this one is on voluminous studies.” In addition, the EPA won’t actually enforce regulations on the biggest emitters, like power plants and refineries, until 2011. That means the plaintiffs can’t prove they’ve suffered any harm from the EPA’s decision, said John Pendergrass, senior attorney at the Environmental Law Institute, who described the lawsuits challenging the endangerment finding as “premature.”

So if the odds of this gambit succeeding are so low, then why is the chamber gearing up for a costly lost cause? The goal of the suit “is political obfuscation,” argues Bill Snape, senior counsel at the Center for Biological Diversity. That is, the chamber’s critics believe that the business lobby group hopes to once again muddy the public understanding of climate change by seeking a high-profile forum in which it can argue that the science isn’t settled. “This is part of a media and political strategy. It’s not a legal strategy,” said David Bookbinder, chief climate counsel at Sierra Club, which has intervened in support of the EPA, along with several other environmental groups and 16 states, many of them litigants in the case that originally prompted the agency’s action.

The EPA’s opponents couldn’t have chosen a better time to argue that the science of global warming is still up for debate, thanks to the recent “ClimateGate” emails scandal, and the revelation that an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report contained flawed data. In reality, the emails released in the so-called ClimateGate flap showed climate scientists behaving unprofessionally over dissenting views, but nothing in the messages discounted the underlying science of climate change, which has been reaffirmed by thousands of peer-reviewed studies from scientists around the world. And although the IPCC’s errors have raised questions about the timing and severity of specific anticipated climate events, they have not altered the overwhelming body of evidence and widespread scientific consensus that the planet is warming due to the burning of fossil fuels. Nevertheless, a number of the legal challenges to the EPA seek to exploit these controversies for maximum PR advantage.

Texas Gov. Rick Perry, for instance, claimed in a press conference announcing his state’s suit that the finding is “based on the tainted data of an agenda-driven international panel.” Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli II accused the agency of introducing “job-destroying regulations based on unverifiable and unrepeatable so-called science.” And the challenge from the Competitive Enterprise Institute, FreedomWorks, and other free-market groups alleges that the hacked emails scandal “has severely undermined EPA’s alleged justification for regulating carbon dioxide.”

For its part, the chamber claims that it’s not attacking the EPA’s scientific assessment. Yet its announcement of the lawsuit did just that—charging that the agency failed to perform “careful analysis of all available data and options” before releasing the “flawed” finding. And in its public comments submitted in advance of the release of the endangerment finding last year, the chamber also disputed the science of climate change, suggesting, among other things, that rising temperatures might actually be beneficial for humans, and that any resulting problems could be addressed by the increased use of air conditioners.

The barrage of lawsuits against the EPA comes as an increasing number of lawmakers in Congress from both parties are moving to attempt to block the agency from cracking down on greenhouse gas emissions. Leading the charge is Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), who, with the help of industry lobbyists, has filed a resolution of disapproval that, if signed into law, would nullify the endangerment finding. This rarely used parliamentary maneuver already has 40 cosponsors, including Democratic Sens. Blanche Lincoln (Ark.), Ben Nelson (Neb.), and Mary Landrieu (La.). A bipartisan trio of representatives introduced the same measure in the House in late February.

While EPA administrator Lisa Jackson has pushed back the enforcement of regulations on the largest emissions sources until 2011, she also has made it clear that rules are coming, whether the EPA’s adversaries like it or not. “The law of the land found that greenhouse gases are pollutants, and they ordered EPA to make a determination,” Jackson told the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee in late February. “I believe I have no choice but to follow the law.” But even if the attempts to block the agency ultimately fail, the lawsuits have given opponents of regulation another platform to attack the science and delay action on climate change further. Says Snape of the Center for Biological Diversity, “If the goal of these lawsuits is to muck up the works, well, unfortunately they’re getting a little bit of traction.”