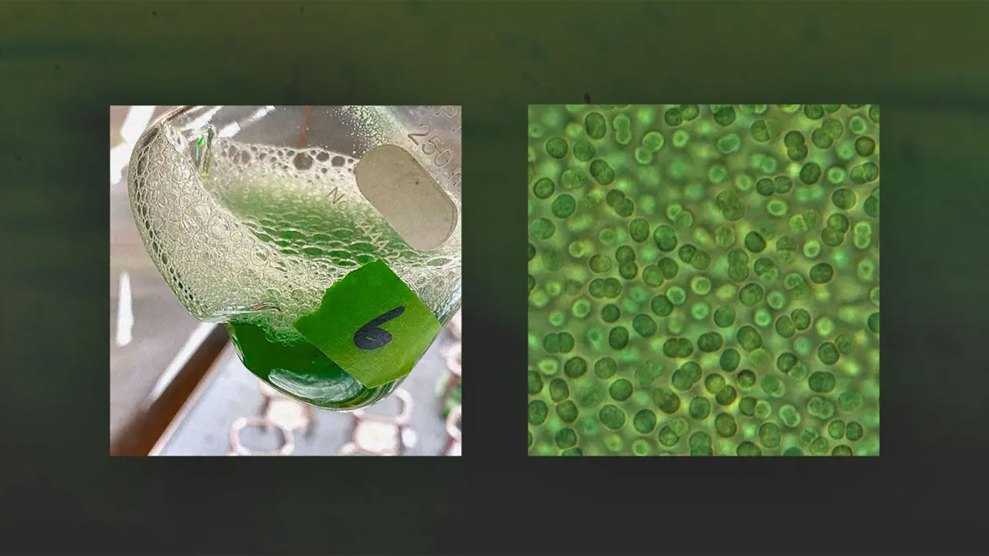

When Henrietta Lacks—a poor, African American tobacco farmer from Virginia—checked into Johns Hopkins Hospital with cervical cancer in 1951, she had no idea that tissue removed from her body without her consent would become one of the most important resources in medical history. She died soon afterward, but her cells, dubbed HeLa, astonished scientists with their still-mysterious “immortality”—they were the first ones to survive indefinitely in the lab, and reproduced at an unprecedented rate. HeLa provided the raw material necessary to develop the polio vaccine and many other medical breakthroughs. In this gripping, vibrant book, Rebecca Skloot looks beyond the scientific marvels to explore the ethical issues behind a discovery that may have saved your life.

Skloot pinpoints HeLa as the origin of many ethical debates that still define modern science, tissue research, and the ownership of the body. Since learning about HeLa in 1973, Lacks’ husband and children have felt betrayed by what they see as a medical establishment that secretly experimented on and exploited black patients. Some of Lacks’ relatives wonder why they shouldn’t get a cut from what is still one of the world’s most popular—and profitable—cell lines: All the HeLa cells ever made would weigh 22 tons; a single vial can sell for nearly $10,000.

Skloot spends nearly 10 years earning the trust of Lacks’ daughter Deborah, who’s also obsessed with learning more about her mother. She still runs up against the Lackses’ understandable suspicion, such as when Deborah slams her up against a wall and asks if she’s really working for Johns Hopkins—but Skloot persists, intent on paying homage to the flesh-and-blood woman behind HeLa.