THERE IS A MAN DRIVING FAST down a dirt road leading to the border. A rooster tail of dust marks his passage. He is very frightened and his 15-year-old son sits beside him in silence. The boy is that way—very bright, yet very quiet. They are unusually close. The father has raised him as a single parent since he was four.

The father and son are fleeing to the United States. Back in their hometown of Ascensión, Chihuahua, men with assault rifles are searching for them. These men are soldiers in the Mexican Army and intend to kill the father, and perhaps the son, also. As the man drives toward the border crossing at Antelope Wells, New Mexico, he thinks the soldiers are ransacking his house. No one in the town will have the guts to speak up.

The man knows this absolutely.

His name is Emilio Gutiérrez Soto and he is a reporter and that is why he is a dead man driving. He recalls how back when Carlos Salinas was president, the Mexican Army came to this same part of northern Chihuahua, beat up a bunch of peasants, tortured prisoners, and terrorized the community under the guise of fighting drug cartels. The peasants never filed any grievances because they knew any complaints would be ignored by their government. Or they would be disappeared. This is the kind of thing the reporter has understood since childhood but does not write and publish. Like the peasants, he knows his place in the system.

It is June 16, 2008, and in two days he will have his 45th birthday, should he live that long.

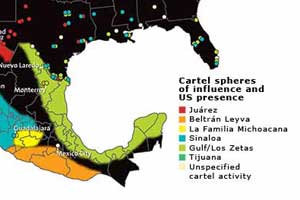

The military has again flooded northern Mexico, ever since President Felipe Calderón assumed office in December 2006 with a margin so razor thin that many Mexicans think he is an illegitimate president. One of his first acts was to declare a war on the nation’s thriving drug industry, and his favorite tool was to be the Mexican Army, portrayed as less corrupt than the local or national police. Now some 45,000 soldiers, nearly 25 percent of the Army, are marauding all over the country, escalating the mayhem that consumes Mexico. In 2008, more than 6,000 Mexicans died in the drug violence, a larger loss than the United States has endured during the entire Iraq War. Since 2000, two dozen reporters have been officially recorded as murdered, at least seven more have vanished, and an unknown number have fled into the United States. But all numbers in Mexico are slippery, because people have so many ways of disappearing. In 2008, 188 Mexicans—cops, reporters, businesspeople—sought political asylum at US border crossings, more than twice as many as the year before. This is the wave of gore the man rides as he heads north.

He has tried to avoid this harsh reality. He has been careful in his work. His publisher has told him it is better to lose a story than to take a big risk. He does not look too closely into things. If someone is murdered, he prints what the police tell him and lets it go at that. If people sell or warehouse drugs in his town, he ignores it. Nor does he inquire about who controls the drug industry in his town or anywhere else.

The man driving is terrified of hitting an Army checkpoint. They are random and they are everywhere. The entire Mexican north has become a killing field. In Palomas, a nearby border town of maybe 7,500 souls, more than 40 men have already been executed in the past year, and several more have vanished in kidnappings; a mass grave was discovered in May. Some of these murders are by drug cartels. Some of these murders are by state and federal police. Some of these murders are by the Mexican Army. There are now many ways to die.

The high desert is beautiful, a pan of creosote with saucers of grass in moist low spots. Here and there volcanic remnants make black marks on the Earth and there is almost no water. Almost all the rivers flowing from the Sierra Madre vanish in the desert. But it is home, the place he has spent his life.

The reporter may die for committing a simple error. He wrote an accurate news story. He did not know that was dangerous because he thought the story was very small and unimportant. He was wrong and that was the beginning of all his trouble.

There are two Mexicos.

There is the one reported by the US press, a place where the Mexican president is fighting a valiant war on drugs, aided by the Mexican Army and the Mérida Initiative, the $1.4 billion in aid the United States has committed to the cause. This Mexico has newspapers, courts, laws, and is seen by the United States government as a sister republic.

It does not exist.

There is a second Mexico where the war is for drugs, where the police and the military fight for their share of drug profits, where the press is restrained by the murder of reporters and feasts on a steady diet of bribes, and where the line between the government and the drug world has never existed.

The reporter lives in this second Mexico.

Until very recently, he liked it just fine. In fact, he loves Mexico and has never thought of leaving. Even though he lives about 20 miles from the border, he has not bothered to cross for almost 10 years.

But now, things have changed. He knows about the humanitarian treaties signed by the United States and he thinks given these commitments, he and his boy will be given asylum. He has decided to tell the authorities nothing but the truth. He has failed to realize one little fact: No Mexican reporter has ever been given political asylum.

Suddenly, he sees a checkpoint ahead and there is no way to escape it.

Men in uniforms pull him over.

He discovers to his relief that this checkpoint is run by Mexico’s migration agency, and so, maybe, they will not give him up to the Army.

“Why are you driving so fast?”

“I am afraid. There are people trying to kill me.”

“The narcos?”

“No, the soldiers.”

“Who are you?”

He hands over his press pass.

“Oh, you are the one, they searched your house.”

“I have had problems.”

“Those sons of bitches do whatever they want. Go ahead. Good luck.”

He roars away. When he stops at the port of entry at Antelope Wells in the bootheel of New Mexico, US customs ask, as they always do, what he is bringing from Mexico.

He says, “We bring fear.”

THE PRIEST GOES to the fiesta to christen a child. The food is lavish, as is the rancho. There are many men of power there, men who have survived the life and now live large and feast on danger. One old man is the boss and he wears a very large gold crucifix encrusted with diamonds and a giant emerald. This gleaming treasure catches the priest’s eye. The padre slips out and goes to the federal police and tells them of this convocation of narcotraficantes. He is a very good source for the police because he hears confession from the men in the life and then sells this information. The police hit the fiesta. They find a lot of cocaine and a million in cash. The priest gets the crucifix as his reward. The cops turn over the rest of the loot to the country’s chief drug enforcement officer at the time. Later it is revealed that this man, Javier Coello Trejo, enforces the law against some cartels, but not the Gulf cartel, which pays him millions for such discretion.

Years later, a long caravan of fine pickup trucks with darkly tinted windows takes up both lanes of the highway leading into Ascensión. There must be 20 or 30 vehicles rumbling into the isolated community of 18,000 in the Chihuahuan desert. The town is surrounded by dying farms, many of them abandoned because of drought and the low prices that came in the wake of the North American Free Trade Agreement. The Army has seized some of these farms and squats on them. People live off a few bars, some small stores, and the drug industry. At the moment the caravan arrives, the streets are empty and no one looks out a single window. There’s a store security videotape of the caravan, but it is impossible to make out any faces behind the glass. Emilio will never know whom this convoy is guarding. He will never ask. Just as the Mexican Army stationed in the town will never record its arrival. Rumors say it is Joaquín “El Chapo” (Shorty) Guzmán Loera, leader of the Sinaloa cartel whom Forbes recently named the 701st richest person in the world. But to investigate such matters is a fatal decision.

Emilio and I are sitting in the sun somewhere in the United States of America as he tosses out the tales of the priest and the strange caravan of fine pickup trucks. He is hiding now with a man who has family and business interests in northern Chihuahua. If it were known he sheltered Emilio, the man’s relatives would be kidnapped and possibly killed, his livelihood jeopardized. As we soak up the sun, Ascensión is in a state of siege. Four women have just vanished and are probably murdered. In October, a parcel containing four heads was delivered to the police station. The director of the bank and his wife have been kidnapped and then returned in bad shape. Also, the bank has just been strafed by machine-gun fire.

In Palomas, a town that like Ascensión falls within the gravitational pull of the sprawling border city of Ciudad Juárez, the entire police force recently resigned, forcing the police chief to seek shelter in the United States. The town is dying. Few people cross from America to shop because of the violence. There is a gray cast to the children begging in the streets that suggests malnutrition. Work has fled—the people-smuggling business has moved because of US pressure in the sector and so the town is studded with half-built or abandoned cheap lodgings for migrants heading north. Also there is an array of narcomansions whose occupants have moved on. And there are eyes everywhere. I walk down the dirt streets tailed by pickups with very darkly tinted windows. The biggest restaurant in town for tourists closes every day at 6 p.m.—get home before dark.

The Mexican Army is everywhere and can be ill tempered. Last year, I was with a friend who took a photograph of soldiers in Palomas a block from the US port of entry, and they came racing at us with machine guns. In April 2008, one of the generals in command of the state held a press conference. “I know that the media are sometimes afraid of us,” he said, “but they should not be afraid. I hope they will trust us.” As for reports of deaths at the hands of the military, the general added, “I would like to see the reporters change their articles. Where they say, ‘one more murdered person,’ they should instead say, ‘one less criminal.'” Reporters were also issued a common explanation by Mexico’s defense department: Yes, there would almost certainly be a spate of robberies and rapes committed by men in uniform but these were to be explained as the deeds of drug traffickers disguising themselves as soldiers to embarrass the Army. Any questions?

EMILIO WAS ONE of eight children born and raised in Nuevo Casas Grandes, a small Chihuahuan city set against the Sierra Madre. His father was a master bricklayer, his mother a housewife. His childhood was poverty. He always wanted to be a writer and worked on the high school paper, a weekly printed on a mimeograph machine.

The Army has a post in his town. One day, a very pretty classmate named Rosa Saenz turns up, her hair and skin coated with mud. Her breasts have been sliced with blades and she has been stabbed 50 times. She has been raped, also. Emilio sees her body in the back of a car in front of the police station, a vehicle dragged in as a monument to a quest for the truth. Two of her classmates are blamed for the murder. The police smash the testicles of one. The other flees and when he returns much later, he is kind of crazy. In the end, no one is charged with the crime. But everyone in the town knows the girl was raped and murdered by the Army. And no one in the town says anything about it.

Emilio is 13 years old.

This is part of basic Mexican schooling: submission. I remember once being in a small town when the then president of Mexico descended like a god with an entourage and massive security. The poor fled into their shanties until it was over. The streets emptied, and when the president did a staged stroll to greet his subjects there was no one standing on the sidewalks except party hacks. Mexican literature is rich with this obliteration of public self and sequestering of private self amid the security of family. The nation’s Nobel laureate, Octavio Paz, etched this trait indelibly in The Labyrinth of Solitude.

Emilio emerges from high school with average grades but a sharp mind in a country where curiosity can be a fatal trait. He learns photography and when he graduates at 18, he is hired by a small paper to take pictures. Soon he is a reporter.

He explains the system in simple terms. Let’s say a reporter earns $100 a week. Every Monday, a man comes who represents the police, the government, the political parties, and the drug leaders. He gives each reporter a sum that is three times his actual wage. This is called the sobre, the envelope.

“Ever since I was a little kid,” he continues, “I listened to my parents criticize bad government. We knew it was corrupt.”

“Corruption at the paper,” he explains, “was subtle. The politicians would win over my boss with dinners and bags of money. The reporter on the beat would sometimes get pressure from the boss not to report certain things like the bad habits of politicians, the houses they own, the girlfriends. And it was understood that you never asked hard questions. The narcos also gave out money but I was always afraid of them. They own businesses and horses, buy ads, have parties with celebrities and you cover that, they would pay you to cover that, but you never mentioned their real business.”

He sees his Mexico as genetically corrupt. A corrupt Aztec ruling class fused with the trash of Spain, the conquistadors. This thesis helps him face the reality around him.

“In Mexico,” he says, “we operate in disguise. There is one face and under that is another mask. Nothing is up-front. The publisher wishes to perpetuate the system. But if it is clear you are taking bribes, you will be fired. You must take it under the table because if you talked about it openly that would affect the image.”

He is entering a bar one night when he sees a local mayor leaving with some narcotraficantes. The mayor pauses by the street, drops his pants, and pisses in the gutter. Emilio writes up the incident—minus the narcos; he is not an idiot—and puts it in the paper. He is young and he does not understand the rules about propriety.

The next day he is called to the mayor’s office.

The mayor is at a big desk with a check ledger.

He says, “How much?”

He wants Emilio to publish a story saying his earlier story was a lie.

Emilio does not take any money. He realizes later that this is a serious error because he learns that the mayor and the publisher are very close.

“I quit and take a job in radio before something bad happens.”

He makes one report on how the drug counselor for the local schools was fired. He wonders on the air if the officials themselves are actually clean. He soon finds out because another local mayor is listening. The mayor has just gotten out of a treatment center in El Paso for cocaine addiction. He storms down to the radio station and offers the owner 10,000 pesos to fire Emilio. The owner obliges.

EMILIO MOVES from paper to paper and eventually winds up at the Ascensión bureau of El Diario, a daily based in nearby Juárez. Emilio loves politics and develops Page 1 stories by dutifully interviewing politicians and publishing their inane answers. It is a wink to the readers—much like La Jornada, a left-of-center Mexico City paper that used to publish articles bought and paid for by the Mexican government in italics. Sometimes when a leading drug figure is arrested, usually as a show to placate US agencies, he interviews them also. He is hard driving, at least until his son is born. After that, he becomes cautious because he must think of his son and not give in to the dangers of ambition.

Here is what a wise man knows: that certain people—the cartel leaders, the corrupt police, the corrupt military—these things cannot be written about at all. That other people should be mentioned favorably unless they are caught in circumstances so extreme that the news cannot be suppressed. Then, the blow is softened as much as possible. Nor are investigations favored. If someone is murdered, you call the proper authorities and you print exactly what they tell you. But you don’t poke around in such matters.

This is the reality of Mexican reporting, where a person is inside but outside, where a person knows more than the public but can only say what is known in code and this code had better not be too clear. He has mastered, he thinks, the rules of the game. He is clean; he avoids taking bribes. But he also ignores the fact that other reporters are taking bribes. He is not looking for trouble. When top military officials say if there are any rapes and robberies they will be the fault of narcotraficantes masquerading as soldiers, well, that is the way it will be reported.

He will obey those instructions for a very simple reason. For three years, Emilio has been afraid he will be murdered by the Mexican Army. He has, to his horror, committed an error. And nothing he has done in the past three years has made up for this mistake. He has ceased reporting on the Army completely. He has focused on safe things such as fighting the creation of a toxic waste facility in the town. He has apologized to various military officers and endured their tongue-lashings. Still, this cloud hangs over him.

He can remember the day he blundered into this dangerous country.

I AM SITTING in the Hotel San Francisco in Palomas almost four years to the day from the moment Emilio Gutiérrez Soto destroyed his life. The small restaurant has eight tables; the walls host an explosion of plastic flowers screaming yellow, red, and pink. Carved wooden mallard heads spike out as hat racks for Stetsons. Music floats through the air, Bob Dylan singing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” In the kitchen, short, dark women chop vegetables for salsa. Their movements are very slow and their faces blank. In the lobby are murals of an imaginary Sierra Madre in an imaginary Mexico. A huge buck stands in an alpine meadow, an eagle swoops down on a lake, a caballero in a sequined suit stares with love at a beautiful señorita. Also in the lobby is a large statue of St. Francis and in his hands and at his feet are handwritten messages and offerings left by migrants. Just five blocks away, the poor plunged through the line and headed into El Norte—but none of the notes are very recent. The river of misery has changed course for the moment.

The tile floor is the color of flesh. The notes whisper of a people in flight: “Father, help us all who pass as wetbacks. Help us Our Father. Bless us all who think of You, who trust in You. And I ask You to bless and help my mother, my father and me and my brothers and sisters and all of my family. In Your hands we place our good luck to pass ALIVE. Adios Our Father.”

Another note says: “Please I ask You with all my heart look after and protect my husband that he pass safely. Amen.” A Bible lies open and someone has dropped this plea on the page:

God bless us and protect us along the way

Yonathan

Manuel

Tomaz

Yumbo

Graciela

Norma

Olinda

Guide us on a good road and protect us.

As I leave the Hotel San Francisco, Johnny Cash is singing,

You can run on for a long time

Run on for a long time

Run on for a long time

Sooner or later God’ll cut you down

Sooner or later God’ll cut you down

IT BEGAN for Emilio on January 28, 2005, when six soldiers came to La Estrella Hotel, a run-down boardinghouse for migrants across the street from the Hotel San Francisco, took food off people’s plates, and then robbed the customers of their money and jewelry. Emilio got tipped off and so he phoned the local police chief. He called the Army also but as is their custom they refused to answer any questions. He filed a brief article about the incident, one of three he wrote during that period noting similar actions by the Army in the area.

That is how he destroyed his life.

Several days later, February 8, 2005, Colonel Filadelfo Martínez Piedra calls Emilio at home, explains that he is “the boss,” and orders him to come immediately to the Hotel Miami in downtown Ascensión. The colonel says, “If you don’t come, we’ll come looking for you at home or wherever you are.”

So he puts his then-11-year-old son in his truck and goes there. He notices scores of ordinary soldiers around the hotel, and two vans full of elite troops who are bodyguards for the officers. He leaves his son in the truck and walks up to the colonel. It is a very cold night.

In his mind, he is thinking, “What the fuck are these cabrones up to?” Soldiers swiftly surround him. The colonel says to another officer, “Look general, the son of a whore who has written all kinds of stupidities has arrived.”

Then the general, Alfonso García Vega, says, “So you are the son of a whore who is lowering our prestige. You son of a fucking whore, you are denigrating us and my boss. The minister in Mexico is extremely bothered by your fucking lies, idiot.”

Emilio tries to form words to excuse himself but he cannot. The general is in charge of Chihuahua. He is very short and his uniform is brilliant with gold trim.

Emilio is very frightened and he says that he only writes what the officials or the victims tell him.

The general says, “No, you have no sources for that information. You made it up. Just how much schooling do you have, asshole?”

Emilio lies, and claims two years of communication studies at a university.

The general explains that Emilio lacks an education equal to his own.

To have a general speak to you is not something to be desired. They can hand out death like a party favor.

The general suggests he should write about drug people.

Emilio says he does not know any and besides they frighten him.

“So, you don’t know them and you fear them,” the general bristles. “You should fear us for we fuck the fucking drug traffickers, you son of a whore. I feel like putting you in the van and taking you to the mountains so you can see how we fuck over the drug traffickers, asshole.”

The guards surround him, he can see his son in the truck about 15 yards away, and the boy looks very frightened. Then people walking past the hotel greet Emilio and he thinks this is what saves him from a beating.

He grovels, apologizes profusely to the general.

“You’ve written idiocies three times and there shall be no fourth. You’d better not mention this meeting or you’ll be sent to hell, asshole.”

The colonel tells him he is under surveillance “and should not fuck up.”

Then, he is dismissed. He gets back in his truck and his son asks what is going on. He says, “They want to kidnap me.” He drives aimlessly, and finally calls his boss at the paper who tells him, “This is serious. This is a problem.”

He decides his only chance at safety is making the threats known. He publishes a third-person account of the incident, and files a complaint with the public safety minister in Nuevo Casas Grandes who warns him, “You better think it over carefully because it is very dangerous getting involved with the military.” But he is building a paper record to try to save himself. He files a complaint against General García Vega and Colonel Martínez Piedra and the soldiers with the National Commission of Human Rights. Three months later the state police begin an investigation that goes nowhere. The representative of the human rights commission proposes a conciliatory act between him and the military. The proposed act is never defined and Emilio knows there will be no reconciliation.

So Emilio does not write anything unseemly about the Army again; he hears no evil and sees no evil. For example, on February 13, 2008, he notes in an unbylined story that “heavily armed commandos” (Emilio now estimates a convoy of 700 men and 100 vehicles) swept the area from Palomas down to Casas Grandes. In Ascensión they ransack the house of Emilio’s friend, a guy who runs a pizza parlor. The friend is given the ley fuga, the traditional game of the military where they let you run and if you can dodge the bullets, you live. His friend is mowed down in the street in front of his home. That night 20 people vanish from the area and only one ever returns, a Chilean engineer who is saved by his embassy. The others simply cease to exist.

But then memory can be a very short-term thing here. Within an hour or two of a killing, there is no one left to describe the murder. In a day, it is a dim memory. In a few days, it is beyond recall except when talking in private to the closest friends and family. This loss of memory is not because of cowardice. It is the wisdom that comes with survival. Emilio knows that the Mexican Army is the only force capable of carrying out a coordinated operation of this kind. In the story he mentions “armed commandos” sweeping the area, a term that to savvy readers means Army and to everyone else indicates a cartel action. That is how an honest reporter tries to avoid becoming a dead reporter. He puts it out of his mind.

BUT THE ARMY has a long memory. After midnight, on May 5, 2008, Emilio awakens to a loud knocking on the door of his home. Fifty soldiers raid the house. Emilio screams, “Press, the press from El Diario,” and a soldier says, “Hands up, asshole. On the ground!”

They tell him they are looking for guns and drugs, and separate him from his stunned son. When they leave, the commander advises him, “Behave well and follow our suggestions.”

On June 14, he steps out of his house and waters his small garden of squash, cantaloupe, watermelon, and cucumbers. He has a pear tree, also an apricot tree, and three rosebushes blooming pink and red. He is going to make his son breakfast, a task he enjoys. It is a Saturday. He notices five guys in a green pickup 70 yards away that look like soldiers and they are watching him. Then, they cruise slowly past him. A while later, they come back but this time in a white vehicle. And they park and watch his house. But there is a store down the block where the soldiers come to buy cocaine and so he thinks just maybe their presence has nothing to do with him.

He is entering a place he will only recognize later: denial. After all, he has behaved properly. Local drug people have offered him money not to mention the tiendas selling cocaine. He’s told them, “Don’t worry. You don’t have to pay me. I am not going to write about them.” Besides, he knows the Army and the police are both involved, so whom is he going to inform? Instead, he’s picked up extra money by writing publicity releases and selling ads for the newspaper.

But he knows, “The hardest part of the job is survive on the salary. That is why the sobres exist.” It has been years since he completely trusted anyone he works with.

He goes inside and makes machaca with eggs for his boy. He tells his son that he is going to his office and that he should keep an eye on the house.

He reads the papers at his desk, then goes three blocks to the police station to talk to a drunk the police have arrested, the usual small moments of a small-town newspaper. Outside, the green pickup is back. He leaves his office around noon and stops by a friend’s welding shop. This time a white vehicle is trailing him. Now he is worried, so he and his friend go to a bodega, buy some beers, and return to the shop. There is a place nearby where people buy cocaine and he sees a soldier from the green pickup go in there and then come out.

Emilio goes home, takes his son to church, and returns to his friend’s shop. After a while he goes out to the bodega again and now the white car is back. Upset, he calls his friend, and tells him to come around to the back of the bodega. He escapes and his friend takes him back to his house.

After church, his son heads to the plaza with friends. Emilio stays at his friend’s and around eight o’clock a woman calls and says, “Emilio, I have to see you right now. Where are you? I can’t talk over the phone.” She comes over and tells him she is dating a soldier and the military people all talk about how they are going to kill him. She is crying. She says, “Emilio, you have to leave now. They are going to kill you.”

Emilio and the woman go to collect his son, then flee to a small ranch about six miles west of Ascensión. He is terrified. Later that night a friend takes him to his house. He wears a big straw hat, slips low in the seat. He sneaks into the house and gets vital documents. All day Sunday Emilio tries to think of a way to save his life and comes up with only one answer: flight. No matter where he goes in Mexico he will have to find a job and use his identity cards and the Army will track him down. He now knows they will never forgive his stories from 2005, that he cannot be redeemed.

He tells his boy, “We are not going back to our house. The soldiers may kill me and I don’t want to leave you alone.”

Monday morning he drives north very fast. He takes all his legal papers so that he can prove who he is. He expects asylum from the government of the United States.

WHAT HE GETS is this: He is immediately jailed, as is his son. They are separated. He is taken to El Paso and placed in a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center run by Deco, Inc. He is deloused, given a blue jumpsuit, and set to work scrubbing floors for a dollar a day. He is denied bond, and no hearing is scheduled. Had he entered the United States illegally and then asked for asylum, he would be eligible for bond. But since he entered legally and asked for asylum at the port of entry he is kept in prison because the Department of Homeland Security declares that Emilio has failed to prove that he “would not pose a danger to the community.”

He remembers those moments he loved: making his son’s breakfast, washing his son’s clothes. Now he can do nothing for him. Emilio cries a lot. He remembers all those bribes, all those sobres, he refused for years. He thinks, “If I had taken bribes I wouldn’t be here in prison.” Instead, he is surrounded by 800 prisoners—Africans, Middle Eastern people, Indians, Russians, and of course Central Americans and Mexicans, swept up in the increasing ICE raids.

“The Mexicans,” he says, “are treated the worst. The staff curses us and calls us rats, narcos, and criminals. The work of the prison is done by the Mexicans and Central Americans. It is ironic—the illegals are arrested for working at real jobs in the US and then they get put in prison and are made to work for nothing.”

For a month, he cannot speak to his son. He is tormented by the fear that older boys might molest him. The prison officials refuse to tell him anything. Finally, he gets a 10-minute phone call. The boy says he is doing okay. Emilio tells him they will not be able to go back to Mexico. He can sense his son is bitter; he has lost his home, his friends, even his dog. Emilio wants to hug him and kiss him as he did each day at home.

The prison is haunted by a Cuban ghost. Twenty years before, it is said, the man hung himself with a bedsheet. And now at night, sometimes all the showers come on, or the toilets are emptied of water. Prisoners say that security cameras see the Cuban in the library in the middle of the night reading. There are sounds of a guitar playing. The ghost is a message that tells Emilio what the prison can do to a man. Emilio’s lawyer explains that asylum will be difficult, but allowing himself to be deported back to Mexico will be fatal. The lawyer says, “Maybe the United States does not want you but we know Mexico does not want you. Think of your son.”

He does. And after a few months, Emilio’s son is released to friends in El Paso. He tells his father not to give up. He tells the press, “I really miss him and I miss my home too, but for me, my dad is more important. Because if something happens to him, I think that I would die. Because he is the only person I have and I love him more than anyone in the world.”

At the end of January 2009, nine days after President Obama is sworn in, Emilio Gutiérrez Soto is suddenly released. When they call him to the office, he assumes he is being shipped to another prison in the American gulag. His lawyer also had no indication of the release. He is reunited with his son.

His first hearing is postponed, and it could be again, because the US government loves postponing such hearings in the hope that migrants will give up and go back home. Emilio cannot work because the US government has yet to give him a work permit.

But Emilio is a creature of hope. He has faith in the new administration because “the race Obama belongs to has been enslaved. I think he shares this history of discrimination with Latinos. And he will realize the huge human rights abuses in Mexico. There are thousands of people like me here. There are thousands of abandoned homes in Juárez alone. If I am sent back to Mexico, I might live a day or a few years. The Army may kill me immediately or wait for my case to grow cold.”

In the meantime, Emilio sits in the sun and tries to teach me Mexico as it is today.

“Mexicans,” he explains, “know the Army is a bunch of brutes. But what is going on now is a coup d’etat by the Army. The president is illegitimate. The Army has installed itself. They have become the government. They are installed in all the state governments. They control the municipal police. They are everywhere but the ministry of education—after all, they are too illiterate to run that. The president has his hands tied and he has tied them.”

But there is another way of looking at the facts on that ground that is un-Mexican with its fetish of a pyramid of power going back to the Aztec emperors, and un-American with our conviction that every place is kind of like our nation only with unsafe water and spicy food. Maybe, the center no longer holds. In the last 10 years, since the death of Amado Carrillo Fuentes, head of the Juárez cartel and first among equals in the drug world, the industry has fragmented into independent baronies and smaller outlaw bands. Since the collapse of the PRI, the ruling party that lasted more than 70 years, Mexico’s civil society has also fragmented, with power leaving the capital and recombining with the narcogangs. The Army, the largest gang, is not attempting to seize the bankrupt and withering state, but grabbing market share in a place whose two largest industries are supplying American drug habits and exporting millions of people. Cartels once imposed constraint of trade. But like soda-pop CEOs, the generals now angle to increase their share of the skyrocketing domestic drug market. And of course, the United States finances this move, via the Mérida Initiative, in the delusion that it is shoring up a republic south of the Rio Grande. We are staring into the future but using old prescription glasses. Murderous cholos on the corner in Juárez and troops marauding and robbing in the disguise of a Mexican drug war may be writing the future while President Obama and President Calderón wander in their bunkers of power, and cling to the fantasies of the ancien régime.

CARLOS SPECTOR, Emilio’s lawyer, is a man on fire. He is 55, red haired, big, El Paso born, a Mexican American Jew. He has built an immigration practice. His childhood was divided between El Paso and Juárez. In his 20s, he moved to Israel under the Law of Return and lived on a kibbutz. But eventually, the border claimed him. He has been looking for a case like Emilio’s for years, a case of a clean Mexican reporter seeking political asylum from the government of the United States. Now he thinks he has it and that he can make American law face the reality of Mexico.

To gain political asylum, applicants must prove they have been persecuted or have a well-founded fear of persecution because of their political opinion or an “immutable characteristic” such as race, religion, or nationality. When it comes to people fleeing Mexico, the United States has quibbled with claims of immutability, telling Mexican cops running from the cartels that they should just stop being a cop, move to another part of Mexico, become a plumber. But Emilio can’t hide from the Army. Those three stories he filed in 2005, the opinions therein, they created an immutable impression on the Army. After that he apologized. He ceased writing anything bad about the Army even when he witnessed them killing people in his town in February 2008. None of this helped. When the Army swept the area again a few months later, they came after him.

Spector says, “The concept of revenge is part of the Mexican political system. Emilio has insulted the institution and it has an incredible memory. The only thing worse he could do, he has done also—to leave the country and denounce it from the US side of the border.”

Almost a month after his release, on February 20, 2009, Emilio held a press conference at the University of Texas-El Paso with Jorge Luis Aguirre, the creator of a website of gossip and news in Juárez who has also fled for his life, and Gustavo de la Rosa Hickerson, the supervising attorney for the State Committee of Human Rights in Chihuahua. They are forming an organization, Periodistas Mexicanos en Exilio, Mexican Journalists in Exile (PEMEXX—a play on PEMEX, the national oil company). They all say the same thing: that the Mexican Army is terrorizing the nation and killing people out of hand.

Aguirre was on his way to the funeral of a reporter murdered in Juárez when he received a call on his cell phone saying he would be next. He promptly fled to El Paso. One reporter at the press conference asks him if he will also apply for asylum, and he answers that he has to think carefully about it since Emilio was jailed for seven months for doing so.

And then Spector says, “This is precisely the reason we formed this organization. Jorge’s fear is legitimate. This was part of the Bush administration’s Guantanamization of the refugee process. By locking people up, especially Mexican asylum applicants, and making them, through a war of attrition, give up their claims. I’ve represented ten cops seeking asylum and not one of them lasted longer than two months. Emilio lasted seven months. On the basis of he had his son, and he knew he was going to be killed. There was nowhere that he could go.”

EMILIO GUTIÉRREZ SOTO and his attorney Carlos Spector sit inside the sanctuary of the United States but the violence of Mexico never lets up. On Tuesday, March 3, four Mexican soldiers visit a friend of Carlos’ in Juárez and hand him a photograph. He does not yet know it, but at that instant, Carlos moves from knowing Mexico to feeling its breath on the back of his neck. In the photo, Carlos is wearing a blue suit and entering the El Paso County Courthouse. The photograph was taken the previous Thursday.

The soldiers say, “Your friend is a criminal and we are looking for him. Tell him to get ahold of us.”

Outside, more men wait in a Hummer.

Carlos gets the call from his friend and falls into his new life. He spent half his childhood living in Juárez. He moves freely and easily in two worlds. And now this seamless web is slashed in half.

He must think, he decides. So he drives to one of El Paso’s many Starbucks and has a cup of coffee. He looks out the window and notices two Ford Expeditions full of men and then he remembers them behind him in traffic as he drove over. He leaves and in his rearview mirror he sees the men in the Expeditions. He executes a sharp U and suddenly he is behind the Fords. They bolt but not before he sees the Chihuahua license plates.

He is learning new facts.

His problem is representing Emilio Gutiérrez Soto. And his problem is real.

His friend in Juárez flees with his family to a distant part of Mexico.

And Carlos can no longer have the life he once enjoyed. He fortifies his house; he starts his car by remote control, standing at a distance.

“It feels like an out-of-body experience,” he says.

He has joined his client and they live in a place beyond courts and laws and the illusions of the United States of America.

He has become a Mexican, body and soul.

Emilio says, “Carlos is now an exile, also.”