Photo courtesy of flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/labor2008/2733055136/" target="blank">aflcio2008</a>.

This article first appeared on Alternet

The best argument for overhauling our ridiculously expensive and dysfunctional health care system — an argument one doesn’t often hear in the corporate media — is that fixing it would put more dollars in your pocket, even if you already have health coverage.

If there’s enough pressure on Congress, we’ll add a well-designed public insurance option to the current mix of private insurance and government health care programs. It would be like (the highly popular) Medicare program, but open to all comers. We’d end up with a very large insurance pool that would lower costs through efficiencies of scale. The plan would be able to drive a hard bargain with providers and cut down on overhead costs, which amount to about 30 percent of spending in the U.S. right now.

And it wouldn’t just contain costs. A publicly administered insurance program would also protect Americans from the kind of health insurance nightmares we hear about so frequently, with families bankrupted by out-of-pocket expenses or stuck in jobs and relationships they hate in order to hold on to their insurance.

But at the end of the day, people are most interested in the heft of their wallets. Ezra Klein argues that if people understood the health care debate in these terms — reform the system and control costs; get a handle on costs and get a pay raise! — it’d be a political game-changer.

“Most workers think stagnant wages mean their employer is paying them less,” he writes. “They don’t know that the main reason for stagnant wages is that their wage increases are going to pay for their health insurance premiums.”

Over the past 30 years, economic growth hasn’t made its way into most working people’s paychecks. But — and this is key — the amount businesses have to pay for an hour of work has increased.

Looking just at the George W. Bush years — and before the current recession gained steam — economists Lawrence Mishel and Jared Bernstein found that while average weekly wages for (nonsupervisory) workers increased by a paltry 1.7 percent annually, average compensation — including health care and other benefits — increased by 5.1 percent per year.

If we stay on our current trajectory — driving fast toward a cliff, as the baby boomers hit their “golden years” — it’s going to get much worse.

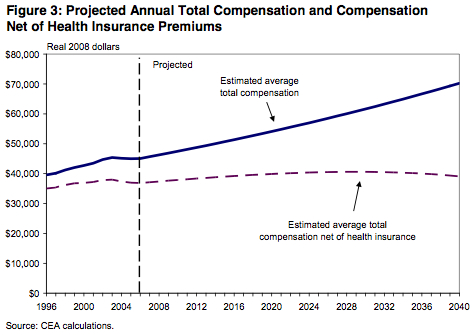

A picture can be worth a thousand words, and this graph, based on projections by the Council of Economic Advisors, shows that Americans’ incomes will remain flat long into the future if rising health costs aren’t better controlled.

The Disease-Care Industry’s Fearmongering

Of course, the usual suspects — the “disease care” industry, corporate-funded think tanks and conservative media outlets — pit us versus them, framing the issue as a “government takeover” of health care.

They invoke images of gray-faced bureaucrats deciding that you need a colonoscopy whether you want one or not, your doctor relegated to the sidelines. They warn that you’ll lose the ability to choose from different plans and providers.

In a column debunking the industry’s “propaganda,” syndicated columnist Froma Harrop dispatched the spin with ease:

What about freedom to choose providers and treatments? Well, private insurance also sets rules on what it will cover and typically provides lists of preferred doctors and hospitals. If your plan lets you go out of the network, you have to pay extra for the privilege. Nothing wrong with that, but we must drop the romantic notion that private coverage affords total freedom at popular prices.

And while the whole point of a public option is to compete with private insurers — using the same efficiencies and economies of scale that big corporations employ all the time to cut costs — the notion that a public option would kill off private insurance is nonsense.

Harrop points out that, “Contrary to the propaganda, a government plan doesn’t tell you what you can have. It tells you what it will pay for. You can buy whatever you want with your own money. And any well-designed plan would allow people to purchase private insurance to cover things the government plan doesn’t.”

In France, where they have a “single-payer” system, 9 out of 10 people buy supplemental insurance from the private sector.

More broadly, they frame the debate as a question of whether hard-working folks will pay higher taxes to cover the uninsured (a large majority of Americans say they’re willing to do so, but it tilts the whole debate to the free-marketeers’ advantage nonetheless).

The reality, though, is that health care is one of those areas where the individual, even the individual with decent insurance, only stands to benefit from the savings that come from genuine competition with a very large insurance pool that doesn’t have to turn a profit for its shareholders.

But I Have Insurance!

Part of the conventional wisdom in the national conversation over health care reform is that if there are around 50 million Americans who lack insurance — give or take — then there are also 250 million who are covered (around 160 million through their employers).

And while Gallup tells us that Americans in general are ranked 18th among citizens of industrialized countries in terms of satisfaction with their health care — while spending more than twice as much per person as top-ranked Ireland — those 160 million people who are covered by their employers are vulnerable to industry-sponsored messages suggesting they could lose their current coverage.

So, it’s important to talk not only about how systemic health care reform might help the 47 million uninsured, but also about what’s in it for the 160 million who have coverage through their jobs.

First, we have to understand that the numbers for the uninsured paint a rosy picture of the depth of the problem. Just consider a few additional points:

- While an estimated 47 million lack insurance today, the number of Americans who have been without coverage at some point in the last two years is almost double that — 87 million, or about 1 in 3 adults under Medicare age.

- And just because you have insurance now doesn’t mean you’ll have it tomorrow. According to an estimate by the AARP, over a quarter-million American companies stopped offering coverage to their employees between 2000-2005.

- And just because you have insurance now doesn’t mean you can afford it — in recent years, the average amount insured employees have had to shell out for premiums has gone up eight times faster than their wages.

- And just because you have insurance doesn’t mean you’re adequately covered. According to an analysis by the Commonwealth Fund, 25 million Americans were underinsured (defined as “people who have health coverage that does not adequately protect them from high medical expenses”) in 2007, up 60 percent since 2003.

Stuck in Dead-End Jobs; Clinging to Bad Marriages

Those are the hard numbers. More difficult to quantify are the ancillary problems with our current system. Anecdotal evidence suggests that more and more people are staying in crappy relationships — or getting married to people they don’t really dig — or clinging desperately to dead-end jobs that they hate in order to keep (or get) coverage

If done right — and the devil is certainly in the details — a public insurance plan would go a long way toward solving these problems. Companies that don’t provide insurance to their employees would be required to pay into the pool. Depending on how the final plan is structured, individuals will probably be required (or at least given incentives) to carry insurance, and those who aren’t raking it in would be able to take advantage of subsidized premiums.

It’s a hybrid plan — somewhere between the fractured for-profit insurance we have now and the kinds of health care systems the citizens of other advanced countries have. And while single-payer advocates (like myself) believe that creating a tax-financed universal insurance system that offers basic care to everyone is the cleanest, most straightforward way of financing health care (and has the greatest potential for savings), the thinking behind the hybrid plan is that it’s vitally important to allow those who enjoy their current insurance to hold onto it.

Those who do would benefit from bringing health spending in line with overall economic growth. Getting a hold of rising health care costs frees up money for other priorities — we currently pay more to Big Health than we spend educating our children, building roads or eating.

And contrary to the spin, getting the uninsured covered will cost less, over the long haul, than leaving them without care. Each and every one of us who has insurance is already spending almost a $1,000 per year to subsidize emergency care (and various unpaid hospital bills) for the uninsured, according to the National Coalition on Health Care.

And even discounting the moral questions of leaving people living in one of the wealthiest countries in the world to fend for themselves, the economics make no sense — it’s far cheaper to treat someone for a cold in a doctor’s office than in the ER. It’s far cheaper to prevent an illness than it is to treat it.

A system with a public option would also break the automatic link between your job (or your spouse’s job) and your insurance. If you want to tell your boss to take that job and shove it — or dump that loser who’s been making you crazy — you can do so comfortable in the knowledge that decent, affordable insurance is available to you.

So if you’re insured, the question isn’t whether you should fight to reform our creaky health care system on behalf of those who don’t have insurance out of the goodness of your heart. If the plan is well designed, the simple fact is it’ll leave you healthy, put some extra dollars in your pocket and free you from the indentured servitude of employer-based health care.