afghanistan has been a playing field for larger geopolitical forces pretty much ever since Alexander the Great invaded in 330 BC. And now, perhaps more than ever, its stability hinges on cooperation from the neighborhood and beyond. The Sunni Saudis have religious and financial clout with the Taliban, much of whose support comes from wealthy Gulf businessmen. Shiite Iran is friendly with the warlords of the erstwhile Northern Alliance; Tehran cooperated with Washington to battle the Taliban until January 2002, when President Bush tarred Iran as part of his “axis of evil.” Like Iran, the Russians want to limit United States and NATO presence in Central Asia. They remain hostile to the Taliban, heirs to the Pashtun warlords who battled them in the ’80s. Like their old satellites, the ‘Stans, they also fear Islamist radicalism spilling over the borders and worry that Afghan instability complicates efforts to export oil and gas from Central Asia. China, for its part, has a voracious appetite for those resources; it also has the cash to help underwrite aid in the region. So does India, which, unbeknownst to most Westerners, is deeply involved in Afghanistan, providing aid, building roads, and opening consulates all over the country. (Its intelligence service, too, is said to be very active there.)

Then, of course, there’s the toughest part of the puzzle—Pakistan, the besieged nuclear powder keg that views Afghanistan as a front in its bitter feud with India. “India is the core of everything that Pakistan security people think about,” explains Rafiq Dossani, a Stanford University scholar who is working on a book about South Asian security. Beginning in 1994, Pakistan’s military intelligence service, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), began building up the Taliban to counterbalance the Northern Alliance (backed by India, Russia, and Iran). But even after the Taliban begat an Islamist insurgency in Pakistan, the Pakistani army has been reluctant to crack down on its monster. Despite more than $10 billion in United States funding, the army has let Pakistan’s ungoverned tribal areas (see Pakistan’s Pashtun Reservation) devolve into a haven for Al Qaeda and insurgents of all stripes; last July’s truck bombing of the Indian Embassy in Kabul is thought to have been carried out by pro-Taliban Afghan warlord Jalaluddin Haqqani on orders from Pakistani intelligence. “The bomb went off as India’s military attaché was coming to work, so it wasn’t just a bomb. It was an assassination,” says Boston University professor Thomas Barfield, who studies the region. “The Indians saw that as a calling card from ISI saying, ‘Get out. This is our territory.’ And they responded by saying, ‘We’re going to give Afghanistan another $400 million.'”

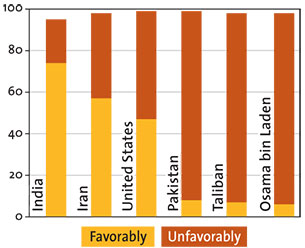

% AFGHANS VIEWING THESE PLAYERS…

Source: BBC/ABC/ARD poll, Feb. 2009

Indeed, while Afghans hold Pakistan responsible for their troubles, India is viewed with favor. (See chart.) Tensions between the two countries have existed since the postcolonial era, and the Pakistani-Afghan border is still contentious—a relic of the 19th-century Great Game, in which England and Russia vied for regional influence. If Pakistan and India reach a deal, it will be a lot easier for Pakistan’s civilian leaders to shift the army’s support away from the Taliban. America’s task is to convince the Pakistani brass that their biggest threat comes not from India, but from their own insurgents, whose conquest of the scenic Swat Valley in February brought them perilously close to the capital. (“This is like rebels taking Fredericksburg,” notes Barfield.)

Even if President Obama can untangle this Gordian knot, Afghanistan will be hopelessly dependent on the largesse of outsiders. It remains to be seen whether the world steps up to help, or turns its back. Again.